Eleanor Rigby

| "Eleanor Rigby" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

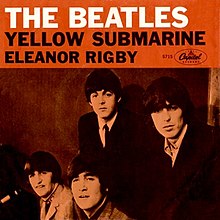

US picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by the Beatles | ||||

| from the album Revolver | ||||

| A-side | "Yellow Submarine" (double A-side) | |||

| Released | 5 August 1966 | |||

| Recorded | 28–29 April & 6 June 1966 | |||

| Studio | EMI, London | |||

| Genre | Baroque pop,[1] art rock[2] | |||

| Length | 2:08 | |||

| Label | Parlophone (UK), Capitol (US) | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Lennon–McCartney | |||

| Producer(s) | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Eleanor Rigby" on YouTube | ||||

"Eleanor Rigby" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album Revolver. It was also issued on a double A-side single, paired with "Yellow Submarine". Credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership, the song is one of only a few in which John Lennon and Paul McCartney later disputed primary authorship.[3] Eyewitness testimony from several independent sources, including George Martin and Pete Shotton, supports McCartney's claim to authorship.[4]

"Eleanor Rigby" continued the transformation of the Beatles from a mainly rock and roll and pop-oriented act to a more experimental, studio-based band. With a double string quartet arrangement by George Martin and lyrics providing a narrative on loneliness, it broke sharply with popular music conventions, both musically and lyrically.[5] The song topped singles charts in Australia, Belgium, Canada, and New Zealand.

Background and inspiration

[edit]Paul McCartney came up with the melody for "Eleanor Rigby" as he experimented on his piano.[6][7] Donovan recalled hearing McCartney play an early version of the song on guitar, where the character was named Ola Na Tungee. At this point, the song reflected an Indian musical influence and its lyrics alluded to drug use, with references to "blowing his mind in the dark" and "a pipe full of clay".[8]

The name of the protagonist that McCartney initially chose was not Eleanor Rigby, but Miss Daisy Hawkins.[9] In 1966, McCartney told Sunday Times journalist Hunter Davies how he got the idea for his song:

The first few bars just came to me. And I got this name in my head – "Daisy Hawkins picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been." I don't know why ... I couldn't think of much more so I put it away for a day. Then the name "Father McCartney" came to me – and "all the lonely people". But I thought people would think it was supposed to be my dad, sitting knitting his socks. Dad's a happy lad. So I went through the telephone book and I got the name McKenzie.[10]

McCartney said that the idea to call his character "Eleanor" was possibly because of Eleanor Bron,[11][12] the actress who starred with the Beatles in their 1965 film Help![10] "Rigby" came from the name of a store in Bristol, Rigby & Evens Ltd.[10] McCartney noticed the store while visiting his girlfriend of the time, actress Jane Asher, during her run in the Bristol Old Vic's production of The Happiest Days of Your Life in January 1966.[13][14] He recalled in 1984: "I just liked the name. I was looking for a name that sounded natural. 'Eleanor Rigby' sounded natural."[12][15][nb 1]

In an October 2021 article in The New Yorker, McCartney wrote that his inspiration for "Eleanor Rigby" was an old lady who lived alone and whom he got to know very well. He would go shopping for her and sit in her kitchen listening to stories and her crystal radio set. McCartney said, "just hearing her stories enriched my soul and influenced the songs I would later write."[19]

Writing collaboration

[edit]McCartney wrote the melody and first verse alone, after which he presented the song to the Beatles when they were gathered in the music room of John Lennon's home at Kenwood.[20] Lennon, George Harrison, Ringo Starr and Lennon's childhood friend Pete Shotton all listened to McCartney play his song through and contributed ideas.[21] Harrison came up with the "Ah, look at all the lonely people" hook. Starr contributed the line "writing the words of a sermon that no one will hear" and suggested making "Father McCartney" darn his socks, which McCartney liked.[21] It was then that Shotton suggested that McCartney change the name of the priest, in case listeners mistook the fictional character for McCartney's own father.[22]

McCartney could not decide how to end the song, and Shotton suggested that the two lonely people come together too late as Father McKenzie conducts Eleanor Rigby's funeral. At the time, Lennon rejected the idea out of hand, but McCartney said nothing and used the idea, later acknowledging Shotton's help.[21] In Lennon's recollection, the final touches were applied to the lyrics in the recording studio,[23] at which point McCartney sought input from Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans, the Beatles' longstanding road managers.[24][25]

"Eleanor Rigby" serves as a rare example of Lennon subsequently claiming a more substantial role in the creation of a McCartney composition than is supported by others' recollections.[26][27] In the early 1970s, Lennon told music journalist Alan Smith that he wrote "about 70 per cent" of the lyrics,[28][29] and in a letter to Melody Maker complaining about Beatles producer George Martin's comments in a recent interview, he said that "Around 50 per cent of the lyrics were written by me at the studios and at Paul's place."[30] In 1980, he recalled writing almost everything but the first verse.[31][32] Shotton remembered Lennon's contribution as being "virtually nil",[33] while McCartney said that "John helped me on a few words but I'd put it down 80–20 to me, something like that."[34] According to McCartney, "In My Life" and "Eleanor Rigby" are the only Lennon–McCartney songs where he and Lennon disagreed over their authorship.[33]

In musicologist Walter Everett's view, the lyric writing "likely was a group effort".[35] Historiographer Erin Torkelson Weber says that, from all the available accounts, McCartney was the principal author of the song and only Lennon's post-1970 recollections contradict this.[36][nb 2] In the same 1980 interview, Lennon expressed his resentment at the way McCartney had sought their bandmates' and friends' creative input, rather than collaborate with Lennon directly. Lennon added, "That's the kind of insensitivity he would have, which upset me in later years."[24] In addition to citing this emotional hurt, Weber suggests that the song's critical acclaim may have motivated Lennon's assertions, as he sought to portray himself as a greater musical genius than McCartney in the years following the Beatles' break-up.[38][nb 3]

Composition

[edit]Music

[edit]The song is a prominent example of mode mixture, specifically between the Aeolian mode, also known as natural minor, and the Dorian mode. Set in E minor, the song is based on the chord progression Em–C, typical of the Aeolian mode and utilising notes ♭ 3, ♭ 6, and ♭7 in this scale. The verse melody is written in Dorian mode, a minor scale with the natural sixth degree.[40] "Eleanor Rigby" opens with a C-major vocal harmony ("Aah, look at all ..."), before shifting to E-minor (on "lonely people"). The Aeolian C-natural note returns later in the verse on the word "dre-eam" (C–B) as the C chord resolves to the tonic Em, giving an urgency to the melody's mood.

The Dorian mode appears with the C# note (6 in the Em scale) at the beginning of the phrase "in the church". The chorus beginning "All the lonely people" involves the viola in a chromatic descent to the 5th; from 7 (D natural on "All the lonely peo-") to 6 (C♯ on "-ple") to ♭6 (C on "they) to 5 (B on "from"). According to musicologist Dominic Pedler, this adds an "air of inevitability to the flow of the music (and perhaps to the plight of the characters in the song)".[41]

Lyrics

[edit]London may have been swinging in 1966, but in the midst of the Cold War, Britain was also a place where faith in the old religions was fading, and where many feared annihilation in an atomic Third World War. There is a bleak end-times feel to "Eleanor Rigby" ...[42]

– Author Howard Sounes

The lyrics represent a departure from McCartney's previous songs, in their avoidance of first- and second-person pronouns and by diverging from the themes of a standard love song.[43] The narrator takes the form of a detached onlooker, akin to a novelist or screenwriter. Beatles biographer Steve Turner says that this new approach reflects the likely influence of Ray Davies of the Kinks, specifically the latter's singles "A Well Respected Man" and "Dedicated Follower of Fashion".[44]

Author Howard Sounes compares the song's narrative to "the isolated broken figures" typical of a Samuel Beckett play, as Rigby dies alone, no mourners attend her funeral, and the priest "seems to have lost his congregation and faith".[42] In Everett's view, McCartney's description of Rigby and McKenzie elevates individuals' loneliness and wasted lives to a universal level in the manner of Lennon's autobiographical "Nowhere Man". Everett adds that McCartney's imagery is "vivid and yet common enough to elicit enormous compassion for these lost souls".[45]

Recording

[edit]"Eleanor Rigby" does not have a standard pop backing. None of the Beatles played instruments on it, although Lennon and Harrison did contribute harmony vocals.[46] Like the earlier song "Yesterday", "Eleanor Rigby" employs a classical string ensemble – in this case, an octet of studio musicians, comprising four violins, two violas and two cellos, all performing a score composed by George Martin.[47] When writing the string arrangement, Martin drew inspiration from Bernard Herrmann's work,[35] particularly the latter's score for the 1960 film Psycho.[48][nb 4]

Whereas "Yesterday" is played legato, "Eleanor Rigby" is played mainly in staccato chords with melodic embellishments. McCartney, reluctant to repeat what he had done on "Yesterday", explicitly expressed that he did not want the strings to sound too cloying. For the most part, the instruments "double up" – that is, they serve as a single string quartet but with two instruments playing each of the four parts. Microphones were placed close to the instruments to produce a more biting and raw sound. Engineer Geoff Emerick was admonished by the string players saying "You're not supposed to do that." Fearing such close proximity to their instruments would expose the slightest deficiencies in their technique, the players kept moving their chairs away from the microphones[51] until Martin got on the talk-back system and scolded: "Stop moving the chairs!" Martin recorded two versions, one with vibrato and one without, the latter of which was used. Lennon recalled in 1980 that "Eleanor Rigby" was "Paul's baby, and I helped with the education of the child ... The violin backing was Paul's idea. Jane Asher had turned him on to Vivaldi, and it was very good."[52]

The octet was recorded on 28 April 1966, in Studio 2 at EMI Studios. The track was completed in Studio 3 on 29 April and on 6 June. Take 15 was selected as the master.[53] The final overdub, on 6 June, was McCartney's addition of the "Ah, look at all the lonely people" refrain over the song's final chorus. This was requested by Martin,[54] who said he came up with the idea of the line working contrapuntally to the chorus melody.[55]

The original stereo mix had the lead vocal alone in the right channel during the verses, with the strings mixed to one channel, while the mono single and mono LP featured a more balanced mix. For the track's inclusion on Yellow Submarine Songtrack in 1999, a new stereo mix was created that centres McCartney's voice and spreads the string octet across the stereo image.[56]

Release

[edit]On 5 August 1966, "Eleanor Rigby" was simultaneously released on a double A-side single, paired with "Yellow Submarine",[57] and on the album Revolver.[58][59] In the LP sequencing, it appeared as the second track, between Harrison's "Taxman" and Lennon's "I'm Only Sleeping".[60] The Beatles thereby broke with their policy of ensuring that album tracks were not issued on their UK singles.[61] According to a report in Melody Maker, the reason for this was to thwart sales of cover recordings of "Eleanor Rigby".[62] Harrison confirmed that they expected "dozens" of artists to have a hit with the song;[63] however, he also said the track would "probably only appeal to Ray Davies types".[64] Writing in the 1970s, music critics Roy Carr and Tony Tyler described the motivation behind the single as a "growing dodge in the ever-innovative music industry", building on UK record companies' policy of reissuing an album's most popular tracks, particularly those that had been culled for release as a single in the US, on a spin-off extended play.[65]

The pairing of a ballad devoid of any instrumentation played by a Beatle and a novelty song marked a significant departure from the content of the band's previous singles.[66][67][nb 5] Writing in his 1977 book The Beatles Forever, Nicholas Schaffner recalled that not only did the two sides have little in common with one another, but "'Yellow Submarine' was the most flippant and outrageous piece the Beatles would ever produce, [and] 'Eleanor Rigby' remains the most relentlessly tragic song the group attempted."[67] Unusually for their post-1965 singles also, the Beatles did not make a promotional film for either of the songs.[69] Music historian David Simonelli groups "Eleanor Rigby" with "Taxman" and the band's May 1966 single tracks "Paperback Writer" and "Rain" as examples of the Beatles' "pointed social commentary" that consolidated their "dominance of London's social scene".[70][nb 6]

In the United States, the record's release coincided with the group's final tour[73] and a public furore over the publication of Lennon's remarks that the Beatles had become "more popular than Jesus Christ";[74][75] he also predicted the downfall of Christianity[76] and described Christ's disciples as "thick and ordinary".[77] In the US South, particularly, some radio stations refused to play the band's music and organised public bonfires to burn Beatles records and memorabilia.[78][79] Capitol Records were therefore wary of the religious references in "Eleanor Rigby" and promoted "Yellow Submarine" as the lead side.[80] During the band's first tour press conference, on 11 August, one reporter suggested that Father McKenzie's sermons going unheard referred to the decline of religion in society. McCartney replied that the song was about lonely individuals, one of whom happened to be a priest.[81][nb 7]

The double A-side topped the Record Retailer chart (subsequently adopted as the UK Singles Chart) for four weeks,[85] becoming their eleventh number-one single on the chart,[86] and Melody Maker's chart for three weeks.[87][88] It was also number 1 in Australia.[89] The single topped charts in many other countries around the world,[90] although "Yellow Submarine" was usually the listed side.[89] In the US, disc jockeys began flipping the single midway through the tour as the radio boycotts were lifted.[91] With each song eligible to chart separately there, "Eleanor Rigby" entered the Billboard Hot 100 in late August[92] and peaked at number 11 for two weeks,[93] and "Yellow Submarine" reached number 2.[94][nb 8]

Critical reception

[edit][In "Eleanor Rigby", the Beatles are] asking where all the lonely people come from and where they all belong as if they really want to know. Their capacity for fun has been evident since the beginning; their capacity for pity is something new and is a major reason for calling them artists.[96]

– Dan Sullivan, The New York Times, March 1967

In Melody Maker's appraisal of Revolver, the writer described "Eleanor Rigby" as a "charming song" and one of the album's best tracks.[97] Derek Johnson, reviewing the single for the NME, said it lacked the immediate appeal of "Yellow Submarine" but "possess[ed] lasting value" and was "beautifully handled by Paul, with baroque-type strings".[98] Although he praised the string arrangement, Peter Jones of Record Mirror found the song "Pleasant enough but rather disjointed", saying, "it's commercial, but I like more meat from the Beatles."[99] Ray Davies offered an unfavourable view[100] when invited to give a song-by-song rundown of Revolver in Disc and Music Echo.[101] He dismissed "Eleanor Rigby" as a song designed "to please music teachers in primary schools",[102] adding: "I can imagine John saying, 'I'm going to write this for my old schoolmistress.' Still it's very commercial."[103]

Reporting from London for The Village Voice, Richard Goldstein stated that Revolver was ubiquitous around the city, as if Londoners were uniting behind the Beatles in response to the antagonism shown towards the band in the US. He wrote: "As a commentary on the state of modern religion, this song will hardly be appreciated by those who see John Lennon as an anti-Christ. But 'Eleanor Rigby' is really about the unloved and un-cared-for."[104] Commenting on the lyrics, Edward Greenfield of The Guardian wrote, "There you have a quality rare in pop music, compassion, born of an artist's ability to project himself into other situations." He found this "Specific understanding of emotion" evident also in McCartney's new love songs and described him as "the Beatle with the strongest musical staying power".[105] While bemoaning that Americans' attention was overly focused on the band's image and non-musical activities, KRLA Beat's album reviewer predicted that "Eleanor Rigby" would "become a contemporary classic", adding that, aside from the quality of the string arrangement, "the haunting melody is one of the most beautiful to be found in our current pop music" and the lyrics "[are] both accurate and unforgettable".[106] Cash Box found the single's pairing "unique" and described "Eleanor Rigby" as "a powerfully arranged, haunting story of sorrow and frustration".[107]

The NME chose "Eleanor Rigby" as its "Single of the Year" for 1966.[108] Melody Maker included the song among the year's five "singles to remember", and Maureen Cleave of The Evening Standard recognised the single and Revolver as the year's best records in her round-up of 1966.[109] At the 9th Annual Grammy Awards in March 1967, "Eleanor Rigby" was nominated in three categories,[110] winning the award for Best Contemporary (R&R) Vocal Performance, Male or Female for McCartney.[111][nb 9]

Appearance in Yellow Submarine film and subsequent releases

[edit]"Eleanor Rigby" appears in the Beatles' 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine as the band's submarine drifts over the desolate streets of Liverpool.[113] Its poignancy ties in quite well with Starr (the first member of the group to encounter the submarine), who is represented as quietly bored and depressed. Starr's character states in his inner thoughts: "Compared with my life, Eleanor Rigby's was a gay, mad whirl."[citation needed] Media theorist Stephanie Fremaux groups the song with "Only a Northern Song" and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" as a scene that most clearly conveys the Beatles' "aims as musicians". In her description, the segment depicts "moments of color and hope in a land of conformity and loneliness".[114] With special effects directed by Charlie Jenkins, the animation incorporates photographs of silhouetted people; bankers with bowler hats and umbrellas are seen on rooftops, overlooking the streets.[114][nb 10]

The track also appears on several of the band's greatest-hits compilations, including A Collection of Beatles Oldies, The Beatles 1962–1966 and 1.[116][117] In 1986, "Yellow Submarine" / "Eleanor Rigby" was reissued in the UK as part of EMI's twentieth anniversary of each of the Beatles' singles and peaked at number 63 on the UK Singles Chart.[118] The 2015 edition of 1 and the expanded 1+ box set includes a video clip for the song, taken from the Yellow Submarine film.[119]

In 1996, a stereo remix of Martin's isolated string arrangement was released on the Beatles' Anthology 2 outtakes compilation.[120] For the song's inclusion on the Love album in 2006, a new mix was created that adds a strings-only portion at the start of the track and closes with a transition featuring part of Lennon's acoustic guitar from the 1968 song "Julia".[121]

The real-life Eleanor Rigby

[edit]

McCartney's recollection of how he chose the name of his protagonist came under scrutiny in the 1980s, after a headstone engraved with the name "Eleanor Rigby" was discovered in the graveyard of St Peter's Parish Church in Woolton, in Liverpool.[14][122] Part of a well-known local family,[9] Rigby had died in 1939 at the age of 44.[16] Close by was a headstone bearing the name McKenzie.[123][124] St Peter's was where Lennon attended Sunday school as a boy,[125] and he and McCartney first met at the church fête there in July 1957.[14] McCartney has said that while he often walked through the churchyard, he had no recollection of ever seeing Rigby's grave.[125] He attributed the coincidence to a product of his subconscious.[123][42] McCartney has also dismissed claims by people who, because of their name and a tenuous association with the Beatles, believed they were the real Father McKenzie.[126]

In 1990, McCartney responded to a request from Sunbeams Music Trust by donating a historical document that listed the wages paid by Liverpool City Hospital; among the employees listed was Eleanor Rigby, who worked as a scullery maid at the hospital.[127][128] Dating from 1911 and signed by the 16-year-old Rigby,[122] the document attracted interest from collectors because of what it seemingly revealed about the inspiration behind the Beatles song.[128] It sold at auction in November 2008 for £115,000. McCartney stated at the time: "Eleanor Rigby is a totally fictitious character that I made up ... If someone wants to spend money buying a document to prove a fictitious character exists, that's fine with me."[127]

Rigby's grave in Woolton became a landmark for Beatles fans visiting Liverpool.[15][129] A digitised image of the headstone was added to the 1995 music video for the Beatles' reunion song "Free as a Bird".[108] Continued interest in a possible connection between the real-life Eleanor Rigby and the 1966 song led to the deeds for the grave being put up for auction in 2017,[15][129] along with a Bible that once belonged to Rigby and a handwritten score for the track (subsequently withdrawn) and other items of Beatles memorabilia.[130]

Legacy

[edit]Sociocultural impact and literary appreciation

[edit]

Although "Eleanor Rigby" was far from the first popular song to deal with death and loneliness, according to Ian MacDonald it "came as quite a shock to pop listeners in 1966".[9] It took a bleak message of depression and desolation, written by a famous pop group, with a sombre, almost funeral-like backing, to the number one spot of the pop charts.[131] Richie Unterberger of AllMusic cites the song's focus on "the neglected concerns and fates of the elderly" as "just one example of why the Beatles' appeal reached so far beyond the traditional rock audience".[66]

In its inclusion of compositions that departed from the format of standard love songs, Revolver marked the start of a change in the Beatles' core audience, as their young, female-dominated fanbase gave way to a following that increasingly comprised more serious-minded, male listeners.[132] Commenting on the preponderance of young people who, under the influence of drugs such as marijuana and LSD, increasingly afforded films and rock music exhaustive analysis, Mark Kurlansky writes: "Beatles songs were examined like Tennyson's poems. Who was Eleanor Rigby?"[133][nb 11]

The song's lyrics became the subject of study by sociologists, who from 1966 began to view the band as spokesmen for their generation.[67] In 2018, Colin Campbell, professor of sociology at the University of York, published a book-length analysis of the lyrics, titled The Continuing Story of Eleanor Rigby.[136] Writing in the 1970s, however, Roy Carr and Tony Tyler dismissed the song's sociological relevance as academics "rear[ing] a mis-shapen skull", adding: "Though much praised at the time (by sociologists), 'Eleanor Rigby' was sentimental, melodramatic and a blind alley."[137][nb 12]

According to author and satirist Craig Brown, the lyrics to "Eleanor Rigby" have been "the most extravagantly praised" of all the Beatles' songs, "and by all the right people".[139] These include poets such as Allen Ginsberg and Thom Gunn, the last of whom likened the song to W.H. Auden's poem "Miss Gee", and literary critic Karl Miller, who included the lyrics in his 1968 anthology Writing in England Today.[140][nb 13]

In his 1970 book Revolt in Style, Liverpudlian musician and critic George Melly admired the "imaginative truth of 'Eleanor Rigby'", likening it to author James Joyce's treatment of his own hometown in Dubliners.[67] Novelist and poet A.S. Byatt recognised the song as having the "minimalist perfection" of a Samuel Beckett story.[16][140] In a talk on BBC Radio 3 in 1993, Byatt said that "Wearing a face that she keeps in a jar by the door" – a line that MacDonald deems "the single most memorable image in The Beatles' output" – conveys a level of despair unacceptable to English middle-class sensibilities and, rather than being a reference to make-up, suggests that Rigby "is faceless, is nothing" once alone in her home.[142]

In 1982, the Eleanor Rigby statue was unveiled on Stanley Street in Liverpool as a donation from Tommy Steele in tribute to the Beatles. The plaque carries a dedication to "All the Lonely People".[143]

In 2004, Revolver appeared second in The Observer's list of "The 100 Greatest British Albums", compiled by a panel of 100 contributors.[144] In his commentary for the newspaper, John Harris highlighted "Eleanor Rigby" as arguably the album's "single greatest achievement", saying that it "perfectly evokes an England of bomb sites and spinsters, where in the darkest moments it does indeed seem that 'no one was saved'". Harris concluded: "Most pop songwriters have always wrapped up Englishness in camp and irony – here, in a rare moment for British rock, post-war Britain is portrayed in terms of its truly grave aspects."[145]

Musical influence and further recognition

[edit]David Simonelli cites the chamber-orchestrated "Eleanor Rigby" as an example of the Beatles' influence being such that, whatever the style of song, their progressiveness defined the parameters of rock music.[146] Music academics Michael Campbell and James Brody highlight the track's melodic shape and imaginative backing to illustrate how, paired with similarly synergistic elements in "A Day in the Life", the Beatles' use of music and lyrics made them one of the two acts in 1960s rock, along with Bob Dylan, who were "most responsible for elevating its level of discourse and expanding its horizons".[147]

Soon after its release, Melly stated that "Pop has come of age" with "Eleanor Rigby", while songwriter Jerry Leiber said, "I don't think there's ever been a better song written."[140] In a 1967 interview, Pete Townshend of the Who commented on the Beatles: "They are basically my main source of inspiration – and everyone else's for that matter. I think 'Eleanor Rigby' was a very important musical move forward. It certainly inspired me to write and listen to things in that vein."[148] In his television show Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, which aired in April 1967, American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein championed the Beatles' talents among contemporary pop acts and highlighted the song's string arrangement as an example of the eclectic qualities that made 1960s pop music worthy of recognition as art.[149] Barry Gibb of the Bee Gees said that their 1969 song "Melody Fair" was influenced by "Eleanor Rigby".[150] America's single "Lonely People" was written by Dan Peek in 1973 as an optimistic response to the Beatles track.[151]

In 2000, Mojo ranked "Eleanor Rigby" at number 19 on the magazine's list of "The 100 Greatest Songs of All Time".[108] In BBC Radio 2's millennium poll, listeners voted it as one of the top 100 songs of the twentieth century.[152] It was ranked at number 137 on Rolling Stone's list "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time" in 2004,[153] and number 243 on the 2021 revised list.[154] "Eleanor Rigby" was inducted into the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences' Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002.[108] It has been a Desert Island Discs selection by individuals such as Cathy Berberian, Charles Aznavour, Patricia Hayes, Carlos Frank and Geoffrey Howe.[140] Similarly, Marshall Crenshaw named it to a list of ten songs that represent perfect songwriting.[155]

Other versions

[edit]By the mid-2000s, over 200 cover versions of "Eleanor Rigby" had been made.[156] George Martin included the song on his November 1966 album George Martin Instrumentally Salutes "The Beatle Girls",[157] one of a series of interpretive works by the band's producer designed to appeal to the easy listening market.[158]

The song was also popular with soul artists seeking to widen their stylistic range.[45] Ray Charles recorded a version that was released as a single in 1968[45] and peaked at number 35 on the Billboard Hot 100[159] and number 36 in the UK.[160] Lennon highlighted it as a "fantastic" cover.[29] Aretha Franklin's version of "Eleanor Rigby" charted at number 17 on the Billboard Hot 100 in December 1969.[161] Music journalist Chris Ingham recognises the Charles and Franklin recordings as notable progressive soul interpretations of the song.[156]

McCartney recorded a new version of "Eleanor Rigby", with Martin again scoring the orchestration,[162] for his 1984 film Give My Regards to Broad Street.[163] Departing from the premise of the film, the song's sequence features McCartney dressed in Victorian costume.[164] On the accompanying soundtrack album, the track segues into a symphonic extension titled "Eleanor's Dream".[165] He has also performed the song frequently in concert, starting with his 1989–90 world tour.[117]

In 2021, composer Cody Fry arranged recordings submitted by 400 musicians into an orchestral cover of "Eleanor Rigby".[166] It was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Arrangement, Instrumental and Vocals at the 64th Annual Grammy Awards.[167]

Personnel

[edit]According to Ian MacDonald:[168]

The Beatles

- Paul McCartney – lead and harmony vocals[169]

- John Lennon – harmony vocals

- George Harrison – harmony vocals

Additional musicians

- Tony Gilbert – violin

- Sidney Sax – violin

- John Sharpe – violin

- Juergen Hess – violin

- Stephen Shingles – viola

- John Underwood – viola

- Derek Simpson – cello

- Norman Jones – cello

- George Martin – string arrangement, conducting

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[180] | Platinum | 600,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

[edit]- ^ Composer Lionel Bart offered another account relating to the song's title.[16][17] He recalled advising McCartney not to call it "Eleanor Bygraves",[17] a name they had seen on a gravestone near Wimbledon Common.[18]

- ^ In a 2007 interview, Martin said that, such was the mutual admiration and sense of competition between the two songwriters, McCartney always took inspiration from Lennon as a lyricist, and while McCartney "wrote all of it", "['Eleanor Rigby'] wouldn't have happened without John's influence."[37]

- ^ Additionally, Weber raises the possibility that manager Allen Klein influenced Lennon's memory. During a 1971 interview, Klein said that he "reminded" Lennon that he "wrote 60 or 70% of the [song's] lyric" and that he "just didn't remember until I sat him down and had him sort through it all".[39]

- ^ Martin originally cited Herrmann's score for Fahrenheit 451,[35][49] but this was a mistake as the film was not released until several months after the recording of "Eleanor Rigby".[50]

- ^ In a radio interview with David Frost shortly before its release, McCartney said he was disappointed with the string arrangement and agreed with a comment he had heard, that the end of the song seemed like a "send-up" of Disney-style storytelling. He added, however, that it was quite normal for the Beatles to initially dislike their new recordings after finishing an album.[68]

- ^ Hunter Davies had intended to make "Eleanor Rigby" the focus of his Atticus column in The Sunday Times when he first visited McCartney in September 1966 and the pair discussed the song.[71] As a result of this association, Davies was chosen to write the Beatles' official biography, published in 1968 as The Beatles: The Authorised Biography.[72]

- ^ At press conferences throughout the August US tour, reporters typically focused on religious matters rather than the band's new music.[82] On 24 August,[83] when asked what had inspired "Eleanor Rigby", Lennon quipped, "Two queers ... Two barrow boys."[84]

- ^ In author Jonathan Gould's description, it was "the first 'designated' Beatles single since 1963" not to top the Billboard Hot 100, a result he attributes to Capitol's caution in initially overlooking "Eleanor Rigby".[95]

- ^ The other categories were Best Vocal Performance, Male and Best Contemporary (R&R) Recording.[110] The Beatles won the Grammy for Song of the Year that night for McCartney's ballad "Michelle".[110][112]

- ^ Reviewing the Yellow Submarine DVD release in 2012 for Record Collector, Oregano Rathbone admired the "Eleanor Rigby" sequence as "an extraordinarily affecting interlude of Magritte melancholia".[115]

- ^ Many of the Beatles' less progressive fans were alienated by the group's new music in 1966, especially Lennon's uncompromising, psychedelic songs.[134] In Beatles Monthly's Revolver readers poll, "Eleanor Rigby" and McCartney's love songs were comfortably the most popular tracks.[135]

- ^ Nicholas Schaffner said that while some of the lines were "trite" and a few critics had found "its pathos veers rather close to bathos", the song succeeded through its "haunting ambiguities".[67] He added that McCartney's next work in the storytelling vein, "She's Leaving Home", about a teenage runaway, was overly literal by comparison, and resembled a soap opera.[138]

- ^ Ginsberg played "Eleanor Rigby", along with "Yellow Submarine" and songs by Bob Dylan and Donovan, to Ezra Pound when visiting him in Venice in 1967. The visit was a gesture by Ginsberg to assure Pound that, despite the latter's embrace of fascism and antisemitism during World War II, his standing as the originator of twentieth-century poetry remained acknowledged in the 1960s.[141]

References

[edit]- ^ Stanley, Bob (20 September 2007). "Pop: Baroque and a soft place". The Guardian. Film & music section, p. 8. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 138.

- ^ Weber 2016, p. 95: "One of the rare songs in which primary authorship is disputed is 'Eleanor Rigby' ..."

- ^ Weber 2016, p. 96: "... [T]here is eyewitness testimony from at least four separate and independent sources, [including Martin, William Burroughs, Donovan and Shotton,] all of whom support McCartney's claim to authorship."

- ^ Campbell & Brody 2008, pp. 172–73.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 282.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 182.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b c MacDonald 2005, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Turner 2016, p. 62.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 282–83.

- ^ a b "Revolver: Eleanor Rigby". beatlesinterviews.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 60, 62.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2012, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Mullen, Tom (11 September 2017). "The Beatles: What really inspired Eleanor Rigby?". BBC News. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Ingham 2006, p. 192.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 203fn.

- ^ Brown 2020, p. 357.

- ^ McCartney, Paul (18 October 2021). "Writing 'Eleanor Rigby'". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 182–83.

- ^ a b c Turner 2005, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 183.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 183, 382.

- ^ a b Rodriguez 2012, p. 82.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Weber 2016, pp. 94–98.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 283.

- ^ a b "Lennon–McCartney Songalog: Who Wrote What". Hit Parader. Winter 1977 [April 1972]. pp. 38–41. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Badman 2001, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 121, 246.

- ^ a b Womack 2014, p. 252.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 283–84.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, p. 51.

- ^ Weber, Erin Torkelson (19 April 2017). "Lennon vs. McCartney: How Beatles History was Written and Re-Written". youtube. Newman University History Department. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Irvin, Jim (March 2007). "The Mojo Interview: Sir George Martin". Mojo. p. 39.

- ^ Weber 2016, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Weber 2016, p. 97.

- ^ Pedler 2003, p. 276.

- ^ Pedler 2003, pp. 333–34.

- ^ a b c Sounes 2010, p. 145.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 61, 63.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, p. 53.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 203–04.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 164.

- ^ Pollack, Alan W. (13 February 1994). "Notes on 'Eleanor Rigby'". Soundscapes. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 134.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 252–53.

- ^ Sheff 2000, p. 140.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 77, 82.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Fontenot, Robert. "'Eleanor Rigby' – The history of this classic Beatles song". oldies.about.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 135–36.

- ^ Sullivan 2013, pp. 318–19.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 84, 200.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 55.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 237–38.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 167.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 68, 329.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 168.

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, pp. 52, 58.

- ^ a b Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles 'Eleanor Rigby'". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Schaffner 1978, p. 62.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 318.

- ^ Simonelli 2013, p. 53.

- ^ Davies, Hunter. "Paperback Writer". In: Mojo Special Limited Edition 2002, p. 93.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 375.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, p. 54.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 101–01.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 57.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 38.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Savage 2015, pp. 315, 324.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 356.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. xii, 174.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 59.

- ^ "One Last Question ...". In: Mojo Special Limited Edition 2002, pp. 60, 62.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 205.

- ^ "All The Number 1 Singles". Official Charts. Retrieved 8 April 2022.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 338.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. xiii, 68.

- ^ a b Sullivan 2013, p. 319.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 85.

- ^ Sutherland 2003, p. 45.

- ^ Savage 2015, p. 329.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 349.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 69.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 356–57.

- ^ Leonard 2014, pp. 121, 279.

- ^ Mulvey, John, ed. (2015). "July–September: LPs/Singles". The History of Rock: 1966. London: Time Inc. p. 78. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ Sutherland 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Green, Richard; Jones, Peter (30 July 1966). "The Beatles: Revolver (Parlophone)". Record Mirror. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Turner 2016, p. 260.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, p. 176.

- ^ Turner 2016, pp. 260–61.

- ^ Staff writer (30 July 1966). "Ray Davies Reviews the Beatles LP". Disc and Music Echo. p. 16.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (25 August 1966). "Pop Eye: On 'Revolver'". The Village Voice. pp. 25–26. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Greenfield, Edward (15 August 2016) [15 August 1966]. "The Beatles release Revolver – archive". theguardian.com. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- ^ Uncredited writer (10 September 1966). "The Beatles: Revolver (Capitol)". KRLA Beat. pp. 2–3. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ "Record Reviews". Cash Box. 13 August 1966. p. 24.

- ^ a b c d Womack 2014, p. 253.

- ^ Savage 2015, pp. 544, 545.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez 2012, p. 198.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 259.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 216.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 238.

- ^ a b Fremaux 2018.

- ^ Rathbone, Oregano (21 June 2012). "Yellow Submarine, The Beatles". Record Collector. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Ingham 2006, pp. 40, 41.

- ^ a b Womack 2014, p. 254.

- ^ Badman 2001, pp. 306, 376.

- ^ Rowe, Matt (18 September 2015). "The Beatles 1 to Be Reissued with New Audio Remixes ... and Videos". The Morton Report. Archived from the original on 29 December 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 143.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 24.

- ^ a b Richards, Sam (12 November 2008). "Revealed: The Real Eleanor Rigby". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b The Beatles 2000, p. 208.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 327.

- ^ a b Turner 2016, p. 63.

- ^ Brown 2020, p. 358.

- ^ a b "Eleanor Rigby paper fetches £115K". BBC News. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Eleanor Rigby Clues Go for a Song". Reuters. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2021 – via Meeja.

- ^ a b "Eleanor Rigby's Grave Goes up for Auction". The Week. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Pidd, Helen (12 September 2017). "Beatles' 'Muse' Eleanor Rigby's Burial Deeds Fail to Go for a Song". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 203–05.

- ^ Jones 2016, pp. 120–21.

- ^ Kurlansky 2005, p. 183.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 53, 63.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 63.

- ^ Brown 2020, p. 362.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, p. 58.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 62, 78.

- ^ Brown 2020, pp. 358–59.

- ^ a b c d Brown 2020, p. 359.

- ^ Kurlansky 2005, p. 133.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 204.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 253–54.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 150.

- ^ Harris, John (20 June 2004). "Revolver, The Beatles". The Observer. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Simonelli 2013, p. 105.

- ^ Campbell & Brody 2008, p. 179.

- ^ "Pop Think-in: Pete Townshend". Melody Maker. 14 January 1967. p. 7.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Hughes, Andrew (2009). The Bee Gees: Tales of the Brothers Gibb. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857120045. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Peek, Dan (2004). An American Band: the America Story. Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1594679292.

- ^ Sullivan 2013, pp. v, 318–19.

- ^ "The Rolling Stone 500 Greatest Songs of All Time 2004: 101-200". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time: 243. The Beatles 'Eleanor Rigby'". Rolling Stone. 15 September 2021. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Porter, David (1 February 2011). "David Porter's 20,000 Things I Love: Marshall Crenshaw". Stereo Embers Magazine. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ a b Ingham 2006, p. 193.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 278.

- ^ Rodriguez 2012, pp. 19, 20.

- ^ "Chart History Ray Charles". billboard.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Ray Charles". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Corpuz, Kristin (25 March 2017). "Happy Birthday, Aretha Franklin! Looking Back at the Queen of Soul's Top 40 Biggest Hot 100 Hits". Billboard. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 428.

- ^ Badman 2001, p. 340.

- ^ Sounes 2010, p. 385.

- ^ Badman 2001, pp. 340–41.

- ^ Whitmore, Laura B. (17 September 2021). "Cody Fry Soars with This Gorgeously Orchestrated Version of 'Eleanor Rigby'". Parade. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Tsioulcas, Anastasia; Harris, LaTesha (23 November 2021). "Jon Batiste, Justin Bieber and Billie Eilish headline 2022 Grammy nominations". NPR. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 203, 205.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 52–53.

- ^ "Go-Set Australian Charts – 5 October 1966". poparchives.com.au. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "The Beatles – Eleanor Rigby". ultratop.be. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "RPM 100 (September 19, 1966)". Library and Archives Canada. 17 July 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- ^ "NZ Listener Chart Summary (The Beatles)". Flavour of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 50: 18 August 1966 through 24 August 1966". The Official UK Charts Company. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles Eleanor Rigby Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 Singles, Week Ending September 24, 1966". cashboxmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Badman 2001, p. 376.

- ^ "Sixties City - Pop Music Charts - Every Week Of The Sixties". Sixtiescity.net. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "British single certifications – Beatles – Eleanor Rigby". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- The Beatles (2000). The Beatles Anthology. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-8118-2684-8.

- Brown, Craig (2020). One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time. London: 4th Estate. ISBN 978-0-00-834000-1.

- Campbell, Michael; Brody, James (2008). Rock and Roll: An Introduction. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-64295-2. Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- Carr, Roy; Tyler, Tony (1978). The Beatles: An Illustrated Record. London: Trewin Copplestone Publishing. ISBN 0-450-04170-0.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

- Fremaux, Stephanie (2018). The Beatles on Screen: From Pop Stars to Musicians. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-5013-2713-1.

- Frontani, Michael R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-966-8.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Ingham, Chris (2006). The Rough Guide to the Beatles. London: Rough Guides/Penguin. ISBN 978-1-84836-525-4.

- Jones, Carys Wyn (2016) [2008]. The Rock Canon: Canonical Values in the Reception of Rock Albums. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7546-6244-0.

- Kurlansky, Mark (2005). 1968: The Year That Rocked the World. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 978-0-345455826.

- Leonard, Candy (2014). Beatleness: How the Beatles and Their Fans Remade the World. New York, NY: Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62872-417-2.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (2nd rev. ed.). London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-828-3.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967). London: Emap. 2002.

- Pedler, Dominic (2003). The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8167-6.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2012). Revolver: How the Beatles Reimagined Rock 'n' Roll. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-61713-009-0.

- Savage, Jon (2015). 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27763-6.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Sheff, David (2000) [1981]. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-25464-4.

- Simonelli, David (2013). Working Class Heroes: Rock Music and British Society in the 1960s and 1970s. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-7051-9.

- Sounes, Howard (2010). Fab: An Intimate Life of Paul McCartney. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723705-0.

- Sullivan, Steve (2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings, Volume 1. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8296-6.

- Sutherland, Steve, ed. (2003). NME Originals: Lennon. London: IPC Ignite!.

- Turner, Steve (2005) [1994]. A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song (New and Updated ed.). New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-084409-7.

- Turner, Steve (2016). Beatles '66: The Revolutionary Year. New York, NY: Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-247558-9.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- Weber, Erin Torkelson (2016). The Beatles and the Historians: An Analysis of Writings About the Fab Four. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-6266-4.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.

External links

[edit]- Full lyrics for the song at the Beatles' official website

- The Beatles' "Eleanor Rigby" on YouTube

- Manuscript Reveals Clues to Beatles Eleanor Rigby Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Howard Goodall's recognition of the role played by Lennon–McCartney in salvaging Western classical music

- 1966 songs

- 1966 singles

- The Beatles songs

- Parlophone singles

- Capitol Records singles

- Songs written by Lennon–McCartney

- Song recordings produced by George Martin

- Songs published by Northern Songs

- UK singles chart number-one singles

- RPM Top Singles number-one singles

- Number-one singles in Germany

- Number-one singles in New Zealand

- Number-one singles in Norway

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Aretha Franklin songs

- Joan Baez songs

- Ray Charles songs

- Tony Bennett songs

- 1960s ballads

- Pop ballads

- Rock ballads

- Songs about fictional female characters

- Songs about poverty

- Songs about loneliness

- Songs about cemeteries

- Songs about death

- Art rock songs

- Baroque pop songs

- The Beatles' Yellow Submarine