Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley | |

|---|---|

| Born | Bridget Louise Riley 24 April 1931 Norwood, London, England |

| Education |

|

| Known for | |

| Movement | Op art |

| Awards |

|

Bridget Louise Riley CH CBE (born 24 April 1931) is an English painter known for her op art paintings.[1] She lives and works in London, Cornwall and the Vaucluse in France.[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Riley was born on 24 April 1931[3] in Norwood, London.[1] Her father, John Fisher Riley, originally from Yorkshire, had been an Army officer. He was a printer by trade and owned his own business. In 1938, he relocated the printing business, together with his family, to Lincolnshire.[4]

At the beginning of World War II, her father, a member of the Territorial Army, was mobilised, and Riley, together with her mother and sister Sally, moved to a cottage in Cornwall.[5] They shared the cottage with an aunt who had studied at Goldsmiths' College, London and Riley attended talks given by a range of retired teachers and non-professionals.[6] She attended Cheltenham Ladies' College (1946–1948) and then studied art at Goldsmiths' College (1949–52), and later at the Royal College of Art (1952–55).[7]

Between 1956 and 1959, she nursed her father, who had been involved in a serious car crash. She suffered a breakdown due to the deterioration of her father's health. After this she worked in a glassware shop. She eventually joined the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency, as an illustrator, where she worked part-time until 1962. The Whitechapel Gallery exhibition of Jackson Pollock in the winter of 1958 had an impact on her.[6]

Her early work was figurative and semi-impressionist. Between 1958 and 1959, her work at the advertising agency showed her adoption of a style of painting based on the pointillist technique.[8]

In 1959 Riley met the painter and art educator Maurice de Sausmarez at a residential summer school that he ran with Harry Thubron and Diane Thubron.[9] He became her friend and mentor, inspiring her to look closer at Futurism and Divisionism and artists such as Klee and Seurat.[10] Riley and de Sausmarez began an intense romantic relationship later that year[11] and spent the summer of 1960 together painting in Italy where they visited the Venice Biennale which was hosting a large exhibition of Futurist art.[10] Riley painted Pink landscape (1960), a pointillist study of the landscape near Radicofani during this holiday.[12] When the relationship ended in autumn of the same year, Riley suffered a personal and artistic crisis, creating paintings that would lead to black and white Op Art works, such as Kiss (1961).[10] She began to develop her signature Op Art style consisting of black and white geometric patterns that explore the dynamism of sight and produce a disorienting effect on the eye and produces movement and colour.[7] Riley and de Sausmarez maintained a professional friendship until his death in 1969.[13] Riley has often cited his role as an early mentor[14] and de Sausmarez's monograph on Riley and her work was published after his death in 1970.[13]

Early in her career, Riley worked as an art teacher for children from 1957 to 1958 at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, Harrow (now known as Sacred Heart Language College). At the Convent of the Sacred Heart, she began a basic design course. Later she worked at the Loughborough School of Art (1959), Hornsey College of Art, and Croydon College of Art (1962–64).[15]

In 1961, she and her partner Peter Sedgley visited the Vaucluse plateau in the South of France, and acquired a derelict farm which they eventually transformed into a studio. Back in London, in the spring of 1962, Victor Musgrave of Gallery One held her first solo exhibition.[6]

In 1968, Riley, with Sedgley and the journalist Peter Townsend, created the artists' organisation SPACE (Space Provision Artistic Cultural and Educational), with the goal of providing artists large and affordable studio space.[16][17]

Seurat's way of seeing

[edit]

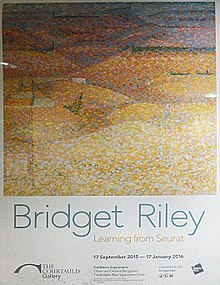

Riley's mature style, developed during the 1960s, was influenced by sources[20] like the French Neo-Impressionist artist Georges Seurat. In 2015–6, the Courtauld Gallery, in its exhibition Bridget Riley: Learning from Seurat, made the case for how Seurat's pointillism influenced her towards abstract painting.[19][21] As a young artist in 1959, Riley saw The Bridge at Courbevoie, owned by the Courtauld, and decided to paint a copy. The resulting work has hung in Riley's studio ever since, barring its loan to the gallery for the exhibition, demonstrating in the opinion of the art critic Jonathan Jones "how crucial" Seurat was to her approach to art.[18] Riley described her copy of Seurat's painting as a "tool", interpreted by Jones as meaning that she, like Seurat, practised art "as an optical science"; in his view, Riley "really did forge her optical style by studying Seurat", making the exhibition a real meeting of old and new.[18] Jones comments that Riley investigated Seurat's pointillism by painting from a book illustration of Seurat's Bridge at an expanded scale to work out how his technique made use of complementary colours, and went on to create pointillist landscapes of her own, such as Pink Landscape (1960),[18] painted soon after her Seurat study[21] and portraying the "sun-filled hills of Tuscany" (and shown in the exhibition poster) which Jones writes could readily be taken for a post-impressionist original.[18] In his view, Riley shares Seurat's "joy for life", a simple but radical delight in colour and seeing.[18]

Work

[edit]It was during this period that Riley began to paint the black and white works for which she first became known. They present a great variety of geometric forms that produce sensations of movement or colour. In the early 1960s, her works were said to induce a variety of sensations in viewers, from seasickness to the feeling of sky diving. From 1961 to 1965, she worked with the contrast of black and white, occasionally introducing tonal scales of grey. Works in this style comprised her first 1962 solo show at Musgrave's Gallery One, as well as numerous subsequent shows. For example, in Fall, a single perpendiculars curve is repeated to create a field of varying optical frequencies.[22] Visually, these works relate to many concerns of the period: a perceived need for audience participation (this relates them to the Happenings, which were common in this era), challenges to the notion of the mind-body duality which led Aldous Huxley to experiment with hallucinogenic drugs;[23] concerns with a tension between a scientific future which might be very beneficial or might lead to a nuclear war; and fears about the loss of genuine individual experience in a Brave New World.[24] Her paintings since 1961, have been executed by assistants.[5] She meticulously plans her composition's design with preparatory drawings and collage techniques; her assistants paint the final canvases with great precision under her instruction.[25]

Riley began investigating colour in 1967, the year in which she produced her first stripe painting.[26] Following a major retrospective in the early 1970s, Riley began travelling extensively. After a trip to Egypt in the early 1980s, where she was inspired by colourful hieroglyphic decoration, Riley began to explore colour and contrast.[27] In some works, lines of colour are used to create a shimmering effect, while in others the canvas is filled with tessellating patterns. Typical of these later colourful works is Shadow Play.

Some works are titled after particular dates, others after specific locations (for instance, Les Bassacs, the village near Saint-Saturnin-lès-Apt in the south of France where Riley has a studio).[28]

Following a visit to Egypt in 1980–81, Riley created colours in what she called her 'Egyptian palette'[29] and produced works such as the Ka and Ra series, which capture the spirit of the country, ancient and modern, and reflect the colours of the Egyptian landscape.[8] Invoking the sensorial memory of her travels, the paintings produced between 1980 and 1985 exhibit Riley's free reconstruction of the restricted chromatic palette discovered abroad. In 1983, for the first time in fifteen years, Riley returned to Venice to once again study the paintings that form the basis of European colourism. Towards the end of the 1980s, Riley's work underwent a dramatic change with the reintroduction of the diagonal in the form of a sequence of parallelograms used to disrupt and animate the vertical stripes that had characterized her previous paintings.[30] In Delos (1983), for example, blue, turquoise, and emerald hues alternate with rich yellows, reds and white.[31]

Murals

[edit]

Riley has painted temporary murals for the Tate, the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and the National Gallery. In 2014, the Imperial College Healthcare Charity Art Collection commissioned her to make a permanent 56-metre mural for St Mary's Hospital, London; the work was installed on the 10th floor of the hospital's Queen Elizabeth Queen Mother Wing, joining two others she had painted more than 20 years earlier.[32] Between 2017 and 2019 Riley completed a large wall painting for the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. This was the largest work she had yet undertaken, covering six of the building's eight walls. The mural referenced her Bolt of Colour of 1983, for the Royal Liverpool University Hospital and made use of a similar palette of Egyptian colours.[33]

On the nature and role of the artist

[edit]Riley made the following comments regarding artistic work in her lecture Painting Now, 23rd William Townsend Memorial Lecture, Slade School of Fine Art, London, 26 November 1996:

Beckett interprets Proust as being convinced that such a text cannot be created or invented but can only be discovered within the artist himself, and that it is, as it were, almost a law of his own nature. It is his most precious possession, and, as Proust explains, the source of his innermost happiness. However, as can be seen from the practice of the great artists, although the text may be strong and durable and able to support a lifetime's work, it cannot be taken for granted and there is no guarantee of permanent possession. It may be mislaid or even lost, and retrieval is very difficult. It may lie dormant, and be discovered late in life after a long struggle, as with Mondrian or Proust himself. Why it should be that some people have this sort of text while others do not, and what 'meaning' it has, is not something which lends itself to argument. Nor is it up to the artist to decide how important it is, or what value it has for other people. To ascertain this is perhaps beyond even the capacities of an artist's own time.[34][35]

Writer and curator

[edit]Riley has written on artists from Nicolas Poussin to Bruce Nauman. She co-curated Piet Mondrian: From Nature to Abstraction (with Sean Rainbird) at the Tate Gallery in 1996.[36] Alongside art historian Robert Kudielka, Riley also served as curator of the 2002 exhibition "Paul Klee: The Nature of Creation", an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London in 2002.[37] In 2010, she curated an artists choice show at the National Gallery in London, choosing large figure paintings by Titian, Veronese, El Greco, Rubens, Poussin, and Paul Cézanne.[38][39]

Exhibitions

[edit]In 1965, Riley exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art in New York City show, The Responsive Eye (created by curator William C. Seitz); the exhibition which first drew worldwide attention to her work and the Op Art movement. Her painting Current, 1964, was reproduced on the cover of the show's catalogue. The absence of copyright protection for artists in the United States at the time, saw her work exploited by commercial concerns which caused her to become disillusioned with such exhibitions. Legislation was eventually passed, following an initiative by New York-based artists, in 1967.[6]

She participated in documentas IV (1968) and VI (1977). In 1968, Riley represented Great Britain in the Venice Biennale, where she was the first British contemporary painter, and the first woman, to be awarded the International Prize for painting.[26] Her disciplined work lost ground to the assertive gestures of the Neo-Expressionists in the 1980s, but a 1999 show at the Serpentine Gallery of her early paintings triggered a resurgence of interest in her optical experiments. "Bridget Riley: Reconnaissance", an exhibition of paintings from the 1960s and 1970s, was presented at Dia:Chelsea in 2000. In 2001, she participated in Site Santa Fe,[40] and in 2003 the Tate Britain organised a major Riley retrospective. In 2005, her work was featured at Gallery Oldham.[41] Between November 2010 and May 2011, her exhibition "Paintings and Related Work" was presented at the National Gallery, London.[42]

In June and July 2014, the retrospective show "Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961–2014" was presented at the David Zwirner Gallery in London.[43][44] In July and August 2015, the retrospective show "Bridget Riley: The Curve Paintings 1961–2014" was presented at the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea.[45]

In November 2015, the exhibition Bridget Riley opened at David Zwirner in New York. The show features paintings and works on paper by the artist from 1981 to present; the fully illustrated catalogue features an essay by the art historian Richard Shiff and biographical notes compiled by Robert Kudielka.[46]

A retrospective exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery, in partnership with the Hayward Gallery, ran from June to September 2019.[47] It showed early paintings and drawings, black-and-white works of the 1960s, and studies that reveal her working methods.[48] This major exhibition of her work, spanning her 70-year career, was also shown at Hayward Gallery from October 2019 to January 2020.[49]

Riley's work was included in the 2021 exhibition Women in Abstraction at the Centre Pompidou.[50]

In May 2023 Riley's first ceiling painting, Verve, was unveiled at The British School at Rome.

Public collections

[edit]- Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal[13]

- Arts Council Collection, London[13]

- British Council Collection, London[13]

- Ferens Art Gallery, Hull[13]

- Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge[13]

- Glasgow Museums Resource Centre, Glasgow[13]

- Government Art Collection, London[13]

- Leeds Art Gallery[13]

- Maclaurin Art Gallery at Rozelle House, Ayr[13]

- Manchester Art Gallery[13]

- Morley College, London[13]

- Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam[51]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston[52]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York[53]

- National Museum Cardiff, Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales[13]

- Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City[54]

- Ruth Borchard Collection[13]

- Southampton City Art Gallery[13]

- Tate, London[13]

- University of Warwick[13]

- Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool[13]

- Whitworth, Manchester[13]

Influence

[edit]

Artists Ross Bleckner and Philip Taaffe made paintings paying homage to the work of Riley in the 80s.[56][57] In 2013, Riley claimed that a wall-sized, black-and-white checkerboard work by Tobias Rehberger plagiarised her painting Movement in Squares and asked for it to be removed from display at the Berlin State Library's reading room.[55][58]

Recognition

[edit]In 1963, Riley was awarded the AICA Critics Prize as well as the John Moores, Liverpool Open Section Prize. A year later, she received a Peter Stuyvesant Foundation Travel bursary. In 1968, she received an International Painting Prize at the Venice Biennale. In 1974, she was named a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.[59] Riley has been given honorary doctorates by Oxford (1993) and Cambridge (1995).[60] In 2003, she was awarded the Praemium Imperiale,[61] and, in 1998, she became one of only 65 Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour in the Commonwealth.[59] As a board member of the National Gallery in the 1980s, she blocked Margaret Thatcher's plan to give an adjoining piece of property to developers and thus helped ensure the eventual construction of the museum's Sainsbury Wing.[5] Riley has also received the Goslarer Kaiserring of the city of Goslar in 2009 and the 12th Rubens Prize of Siegen in 2012.[62] Also in 2012, she became the first woman to receive the Sikkens Prize, the Dutch art prize recognising the use of colour.[63]

Philanthropy

[edit]Riley is a Patron of Paintings in Hospitals, a charity established in 1959 to provide art for health and social care in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.[64]

Between 1987 and 2014, she created three murals across the eighth, ninth and tenth floors of the Queen Elizabeth Queen Mother Wing, St Mary's Hospital, London.[65]

Since 2016 the Bridget Riley Art Foundation has funded the Bridget Riley Fellowship at the British School at Rome.[66][67]

In 2017, alongside Yoko Ono and Tracey Emin, Riley donated artworks to an auction to raise money for Modern Art Oxford.[68]

Art market

[edit]- 2006, Untitled (Diagonal Curve) (1966), a black-and-white canvas of dizzying curves, was bought by Jeffrey Deitch at Sotheby's for $2.1 million, nearly three times its $730,000 high estimate and also a record for the artist.[69]

- February 2008, the artist's dotted canvas Static 2 (1966) brought £1,476,500 ($2.9 million), far exceeding its £900,000 ($1.8 million) high estimate, at Christie's in London.[70]

- July 2008, Chant 2 (1967), part of the trio shown in the Venice Biennale, went to a private American collector for £2,561,250 ($5.1 million), at Sotheby's.[71]

- March 2022, Gala (1974) sold for £4,362,000 ($5.8 million) at the 2022 Modern British Art Evening Sale in Christie's, London.[72]

Bibliography

[edit]- Bridget Riley A Very Very Person: The Early Years (London: Ridinghouse, 2019). Text by Paul Moorhouse. ISBN 9781909932500

- Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961–2014 (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2014). Texts by Robert Kudielka, Paul Moorhouse, and Richard Shiff. ISBN 9780989980975[73]

- Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961–2012 (London: Ridinghouse; Berlin: Holzwarth Publications and Galerie Max Hetzler, 2013). Texts by John Elderfield, Robert Kudielka and Paul Moorhouse.[74]

- Bridget Riley: Works 1960–1966 (London: Ridinghouse, 2012). Bridget Riley in conversation with David Sylvester (1967) and with Maurice de Sausmarez (1967).

- Bridget Riley: Complete Prints 1962–2012 (London: Ridinghouse, 2012). Essays by Lynn MacRitchie and Craig Hartley; edited by Karsten Schubert.

- The Eye's Mind: Bridget Riley. Collected Writings 1965–1999 (London: Thames & Hudson, Serpentine Gallery and De Montfort University, 1999). Includes conversations with Alex Farquharson, Mel Gooding, Vanya Kewley, Robert Kudielka, and David Thompson. Edited by Robert Kudielka.

- Bridget Riley: Paintings from the 60s and 70s (London: Serpentine Gallery, 1999). With texts by Lisa Corrin, Robert Kudielka, and Frances Spalding.

- Bridget Riley: Selected Paintings 1961–1999 (Düsseldorf: Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen; Ostfildern: Cantz Publishers, 1999). With texts by Michael Krajewski, Robert Kudielka, Bridget Riley, Raimund Stecker, and conversations with Ernst H. Gombrich and Michael Craig-Martin.

- Bridget Riley: Works 1961–1998 (Kendal, Cumbria: Abbot Hall Art Gallery and Museum, 1998). A conversation with Isabel Carlisle.

- Bridget Riley: Dialogues on Art (London: Zwemmer, 1995). Conversations with Michael Craig-Martin, Andrew Graham Dixon, Ernst H. Gombrich, Neil MacGregor, and Bryan Robertson. Edited by Robert Kudielka and with an introduction by Richard Shone.

- Bridget Riley: Paintings and Related Work (London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2010). Text by Colin Wiggins, Michael Bracewell, Marla Prather and Robert Kudielka. ISBN 978 1 85709 497 8.

- Follin, Frances (2004). Embodied Visions: Bridget Riley, Op Art and the Sixties. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-097643-2.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Bridget Riley born 1931". Tate.

- ^ Bridget Riley: Reconnaissance, September 21, 2000 – June 17, 2001 Archived 5 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dia Art Foundation, New York.

- ^ "Bridget Riley". Art UK. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Olly Payne (2012). "Bridget Riley". op-art.co.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Mary Blume (19 June 2008), Bridget Riley retrospective opens in Paris The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Kudielka, Robert (2010). "Chronology". Bridget Riley: Paintings and Related Work. London: National Gallery Company Limited. pp. 67–72. ISBN 978-1-8570-9497-8..

- ^ a b Chilvers, Ian & Glaves-Smith, John eds., Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. pp. 598–599

- ^ a b Bridget Riley Museum of Modern Art, New York.

- ^ On Artists and Their Making: Selected Writings of Maurice de Sausmarez. London: Unicorn Press Publishing Group. 2015. ISBN 978-1-910065-84-6.

- ^ a b c Riley, Bridget; Moorhouse, Paul; Tate Britain, eds. (2003). Bridget Riley: on the occasion of the exhibition at Tate Britain, London 26 June - 28 September 2003. London: Tate Publ. ISBN 978-1-85437-492-9.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (28 September 2000). "Not so square after all". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ De Sausmarez, Maurice (1970). Bridget Riley. London: Studio Vista. ISBN 978-0-289-79810-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t CMS, Keepthinking – Qi. "Art UK | Home". artuk.org. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ Maurice de Sausmarez 1915-1969. The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery. 2015. ISBN 9781874331551.

- ^ "Bridget Riley, born 1931: Artist Biography". tate.org.uk. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "The SPACE Story". Archived from the original on 10 May 2011.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (5 July 2008). "The life of Riley: Jonathan Jones interview with Bridget Riley, art world star of the 60s". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jones, Jonathan (16 September 2015). "Bridget Riley review – pounding psychedelic art that will make you see the world differently". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Bridget Riley: Learning from Seurat". The Courtauld Gallery. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Grosenick, Uta; Becker, Ilka (28 October 2001). Women Artists in the 20th and 21st Century. Taschen. ISBN 9783822858547 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Sooke, Alastair (21 September 2015). "Bridget Riley: Learning from Seurat, Courtauld, review: 'a rare insight into an artist's mind'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ Bridget Riley, Fall (1963) Tate.

- ^ Huxley, Aldous (1954) The Doors of Perception, Chatto and Windus, p. 15

- ^ Introduction to Frances Follin, Embodied Visions: Bridget Riley, Op Art and the Sixties, Thames and Hudson 2004

- ^ Practising Abstraction, Bridget Riley talking to Michael Craig-Martin in Bridget Riley, Dialogues on Art, p. 62

- ^ a b "Press Release: Bridget Riley". Tate Gallery. 17 March 2003. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- ^ Things to Enjoy, Bridget Riley, talking to Bryan Robertson in Bridget Riley, Dialogues on Art, p. 87

- ^ Karen Rosenberg (21 December 2007), Bridget Riley The New York Times.

- ^ Bridget Riley, Ka 3 (1980) Christie's 20th Century British Art, London, 6 June 2008.

- ^ Bridget Riley, August (1995) Christie's Post-War & Contemporary Art Evening Sale, London, 30 June 2008.

- ^ Jörg Heiser (May 2011), Bridget Riley at Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Frieze.

- ^ Caroline Davies (6 April 2014), Bridget Riley's bold colours boost London hospital ward The Guardian.

- ^ "Chinati Announces A Large-scale New Wall Painting By Bridget Riley Opening In October | The Chinati Foundation | La Fundación Chinati". chinati.org.

- ^ Bracewell, Michael (October 2008). "Seeing is Believing". Frieze Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Riley, Bridget (September 1997). "Painting Now". The Burlington Magazine. 139 (1134). The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd.: 616–622. JSTOR 887465.

- ^ Bridget Riley The Stripe Paintings 1961–2014, June 13 – July 25, 2014 David Zwirner, London.

- ^ Alan Riding (10 March 2002), The Other Klee, the One Who's Not on Postcards The New York Times.

- ^ Hilary Spurling (27 November 2010), Bridget Riley at the National Gallery – review The Guardian.

- ^ Martin Gayford (10 December 2010), Colors Shimmer as Bridget Riley Confronts Old Masters: Review Bloomberg.

- ^ Christopher Knight (25 November 2000), Seeing the Top of the Op Artists Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Tom Bendhem: Collector". Oldham Council. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ "Bridget Riley Paintings and Related Work". National Gallery. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "The Stripe Paintings 1961–2014". David Zwirner. 25 July 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ Wullschlager, Jackie (6 June 2014). "Bridget Riley: a London retrospective". FT.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Bridget Riley: The Curve Paintings 1961–2014". De La Warr Pavilion. 5 August 2015. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ "Bridget Riley". David Zwirner Books. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ^ "Exhibition ¦ Coming Soon – Bridget Riley". Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Art Fund – Bridget Riley Exhibition". Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Bridget Riley review – a shimmering, rolling, flickering spectacular". The Guardian. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Women in abstraction. London : New York, New York: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ; Thames & Hudson Inc. 2021. p. 170. ISBN 978-0500094372.

- ^ "Boijmans Collection Online". Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

- ^ "Bridget Riley". Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Bridget Riley". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "Works of: Bridget Riley". Nelson-Atkins. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b Julia Michalska (15 January 2014), Agreement reached in plagiarism row between artists Archived 17 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper.

- ^ Sheets, Hilarie (21 May 2010). "Bridget Riley". Art+Auction. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ "Eyes Wide Open". The Guardian. 21 June 1999. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ The two paintings can be seen side by side at: "Riley / Rehberger plagiarism row reaches agreement". Op-art. 17 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Bridget Riley: From Life – National Portrait Gallery". www.npg.org.uk. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Cooke, Lynne (2001). Bridget Riley: reconnaissance. New York: Dia Center for the Arts. p. 106. ISBN 0-944521-41-X.

- ^ Louise Roug (23 October 2003), Five luminaries to receive arts awards Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Sikkens Foundation Biography". Archived from the original on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ "BBC News – Bridget Riley receives Dutch art prize". Bbc.co.uk. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Wrathall, Claire (13 October 2017). "Exploring the palliative power of art". howtospendit.ft.com. Retrieved 18 December 2018. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bridget Riley – Imperial Charity". www.imperialcharity.org.uk. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "The Bridget Riley Fellowship". The Bridget Riley Art Foundation. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "awards-residencies-fine-arts". bsr.ac.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Yoko Ono says "I Love U" to Modern Art Oxford by donating valuable painting". Oxford Mail. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Carol Vogel (26 June 2006), Prosperity Sets the Tone at London Auctions The New York Times.

- ^ "Bridget Riley (b. 1931) | Static 2 | POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Auction | 1960s, Paintings | Christie's". Christies.com. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.sothebys.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Modern British and Irish Art Evening Sale | Gala". Christie's. 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023.

- ^ "David Zwirner Books · Bridget Riley: The Stripe Paintings 1961–2014". David Zwirner Books.

- ^ "Publications". Karstenschubert.com. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

External links

[edit]- 36 artworks by or after Bridget Riley at the Art UK site

- The Pace Gallery

- Ongoing exhibitions of Bridget Riley Archived 10 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Bridget Riley exhibition at Abbot Hall Art Gallery, 1998-9

- Jonathan Jones, The Life of Riley (interview), The Guardian, 5 July 2008

- "At the end of my pencil" article by Bridget Riley, London Review of Books

- Slideshow of paintings in Bridget Riley's Museum für Gegenwartskunst retrospective, 2012

- Exhibition of Bridget Riley's work at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2017

- Interview with Bridget Riley, 1978 May 10, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- 1931 births

- Living people

- 20th-century English painters

- 21st-century English painters

- 20th-century English women artists

- 21st-century English women artists

- Alumni of Goldsmiths, University of London

- Alumni of Loughborough University

- Alumni of the Royal College of Art

- British abstract artists

- British contemporary painters

- British women curators

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- English contemporary artists

- English printmakers

- English women painters

- Members of the Academy of Arts, Berlin

- Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour

- Op art

- Painters from London

- People educated at Cheltenham Ladies' College

- Artists from London

- People from Lambeth

- People from Vaucluse

- British women printmakers