Major Barbara

| Major Barbara | |

|---|---|

The Court Theatre 1904–1907 | |

| Written by | George Bernard Shaw |

| Date premiered | November 28, 1905[1] |

| Place premiered | Court Theatre |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Drama |

| Setting | London |

Major Barbara is a three-act English play by George Bernard Shaw, written and premiered in 1905 and first published in 1907. The story concerns an idealistic young woman, Barbara Undershaft, who is engaged in helping the poor as a Major in the Salvation Army in London. For many years, Barbara and her siblings have been estranged from their father, Andrew Undershaft, who now reappears as a rich and successful munitions maker. The father gives money to the Salvation Army, which offends Barbara because she considers it "tainted" wealth. The father argues that poverty is a worse problem than munitions and claims that he is doing more to help society by giving his workers jobs and a steady income than she is doing by giving people free meals in a soup kitchen.[2]

The play script displays typical Shavian techniques in the omission of apostrophes from contractions and other punctuation, the inclusion of a didactic introductory essay explaining the play's themes, and the phonetic spelling of dialect English, as when Bill Walker jeers, "Wot prawce selvytion nah?" (What price salvation now?).

Setting

[edit]- London

- Act I: Lady Britomart's house in Wilton Crescent

- Act II: The Salvation Army shelter in West Ham

- Act III: Lady Britomart's house, later at the Undershaft munitions works in Perivale St. Andrews

Synopsis

[edit]An officer of The Salvation Army, Major Barbara Undershaft, becomes disillusioned when her Christian denomination accepts money from an armaments manufacturer (her father) and a whisky distiller. She eventually decides that bringing a message of salvation to people who have plenty will be more fulfilling and genuine than converting the starving in return for bread.

Although Barbara initially regards the Salvation Army's acceptance of Undershaft's money as hypocrisy, Shaw did not intend that it should be thought so by the audience. Shaw wrote a preface for the play's publication, in which he derided the idea that charities should only take money from "morally pure" sources, arguing that using money to benefit the poor will have more practical benefit than ethical niceties. He points out that donations can always be used for good whatever their provenance, and he quotes a Salvation Army officer, "they would take money from the devil himself and be only too glad to get it out of his hands and into God's."

Plot

[edit]

Lady Britomart Undershaft, the daughter of a British earl, and her son Stephen discuss a source of income for her grown daughters Sarah, who is engaged to Charles Lomax (a slightly comic figure who continually stupidly says "Oh, I say!"), and Barbara, who is engaged to Adolphus Cusins (a scholar of Greek literature). Lady Britomart leads Stephen to accept her decision that they must ask her estranged husband, Andrew Undershaft, for financial help. Mr. Undershaft is a successful and wealthy businessman who has made millions of pounds from his munitions factory, which manufactures the world-famous Undershaft guns, cannons, torpedoes, submarines and aerial battleships.

When their children were still small, the Undershafts separated; now grown, the children have not seen their father since, and Lady Britomart has raised them by herself. During their reunion, Undershaft learns that Barbara is a major in The Salvation Army who works at their shelter in West Ham, east London. Barbara and Mr. Undershaft agree that he will visit Barbara's Army shelter, if she will then visit his munitions factory.

A subplot involves the down-and-out and fractious visitors to the shelter, including a layabout painter and con artist (Snobby Price), a poor housewife feigning to be a fallen woman (Rummy Mitchens), an older laborer fired for his age (Peter Shirley), and a pugnacious bully (Bill Walker) who threatens the inhabitants and staff over his runaway partner, striking a frightened care worker (Jenny Hill).

When he visits the shelter, Mr. Undershaft is impressed with Barbara's handling of these various troublesome people who seek social services from the Salvation Army: she treats them with patience, firmness, and sincerity. Undershaft and Cusins discuss the question of Barbara's commitment to The Salvation Army, and Undershaft decides he must overcome Barbara's moral horror of his occupation. He declares that he will therefore "buy" (off) the Salvation Army. He makes a sizeable donation, matching another donation from a whisky distiller. Barbara wants the Salvation Army to refuse the money because it comes from the armaments and alcohol industries, but her supervising officer eagerly accepts it. Barbara sadly leaves the shelter in disillusionment, while Cusins views Undershaft's actions both with disgust and sarcastic pleasure.

According to tradition, the heir to the Undershaft fortune must be an orphan who can be groomed to run the factory. Lady Britomart tries to convince Undershaft to bequeath the business to his son Stephen, but neither man consents. Undershaft says that the best way to keep the factory in the family is to find a foundling and marry him to Barbara. Later, Barbara and the rest of her family accompany her father to his munitions factory. They are all impressed by its size and organisation. Cusins declares that he is a foundling, and is thus eligible to inherit the business. Undershaft eventually overcomes Cusins' moral scruples about the nature of the business, arguing that paying his employees provides a much higher service to them than Barbara's Army service, which only prolongs their poverty; as an example, the firm has hired Peter. Cusins' gradual acceptance of Undershaft's logic makes Barbara more content to marry him, not less, because bringing a message of salvation to the factory workers, rather than to London slum-dwellers, will bring her more fulfilment.

Production history

[edit]

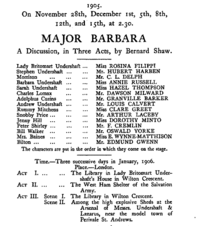

The play was first produced at the Court Theatre in London in 1905 by J.E. Vedrenne and Harley Granville-Barker. Barker also played Cusins, alongside Louis Calvert, Clare Greet, Edmund Gwenn, Oswald Yorke and Annie Russell. The Broadway premiere in the United States was at the Playhouse Theatre on 9 December 1915.

A film adaptation of 1941 was produced by Gabriel Pascal, and starred Wendy Hiller as Barbara, Rex Harrison as Cusins and Robert Morley as Undershaft.

A Broadway production in 1956 with Charles Laughton and Burgess Meredith is noted in the discussion following Laughton's guest appearance on What's My Line on 25 November 1956. Meredith was on the panel.

Caedmon Records released a 4-LP recording of the play in 1965 (TRS 319 S) directed by Howard Sackler with Warren Mitchell as Bill Walker, Maggie Smith as Barbara, Alec McCowen as Cusins, Celia Johnson as Lady Britomart and Robert Morley as Undershaft.

A TV movie production was broadcast in 1966 with Eileen Atkins as Barbara, Douglas Wilmer as Undershaft and Daniel Massey as Cusins.[3]

The play has been produced a number of times for BBC Radio:

- 1955, BBC Light Programme with Irene Worth as Barbara, Anthony Jacobs as Cusins and Frank Pettingell as Undershaft

- 1962, BBC Third Programme with Joyce Redman, Esme Percy and Eliot Makeham

- 1961, BBC Third Programme with June Tobin as Barbara, Richard Hurndall as Cusins and Malcolm Keen as Undershaft

- 1967, BBC Home Service with Dorothy Tutin as Barbara, Alec McCowen as Cusins and Max Adrian as Undershaft

- 1980, BBC Radio 4 with Anna Massey as Barbara, Jeremy Clyde as Cusins and John Phillips as Undershaft

- 1998, BBC Radio 3 with Jemma Redgrave as Barbara, David Yelland as Cusins and Peter Bowles as Undershaft

- 2015, BBC Radio 4 in 2 episodes with Eleanor Tomlinson as Barbara, Jack Farthing as Cusins and Matthew Marsh as Undershaft

Background

[edit]Lady Britomart Undershaft was modelled on Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle, the mother-in-law of Gilbert Murray, who with his wife Lady Mary served as inspiration for Adolphus Cusins and Barbara Undershaft.[2][4]

Andrew Undershaft was loosely inspired by a number of figures, including the arms dealer Basil Zaharoff, and German armaments family Krupp. Undershaft's unscrupulous sale of weapons to any and all bidders, as well as his government influence and more pertinently his company's method of succession (to a foundling rather than a son), tie him especially to Krupp steel. Friedrich Alfred Krupp died by suicide in 1902 following publication of claims he was a homosexual. His two daughters were his heirs. Undershaft shares a name with a Church of England church in the City of London named St Andrew Undershaft; given the district's longstanding status as the financial centre of London, the association underscores the play's thematic emphasis on the interpenetration of religion and economics, of faith and capital.

Analysis

[edit]Sidney P. Albert, a noted Shaw scholar, analysed various aspects of the play in several articles. These include first, Shaw's own account of the writing of the play;[5] second, the chosen time of the play's setting, January 1906,[6] and third, references to the Lord's Prayer[7]

Several scholars have compared this work to other works, including one of Shaw's own, and others from different periods. Fiona Macintosh has examined Shaw's use of classical literary sources, such as The Bacchae, in Major Barbara.[8] In his discussion of the play, Robert J Jordan has analysed the relationship between Major Barbara and another Shaw play, Man and Superman.[9] Joseph Frank has examined parallels between the play and the Divine Comedy of Dante.[10] J.L. Wiesenthal has discussed parallels with the play and Shaw's personal interpretations of Richard Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen.[11]

Many studies have looked at main character Undershaft's beliefs and morals from several points of view, including their relation to Shaw's personal beliefs; their presentation throughout the play, and their changes over the course of the play; the counterpoints to them by Adolphus Cusins, and their relation to the social realities of the day. First, Charles Berst has studied the convictions of Andrew Undershaft in the play, and compared them with Shaw's own philosophical ideas.[12] Robert Everding has discussed the gradual presentation of the ideas and character of Andrew Undershaft as the play progresses.[13] The pseudonymous commentator 'Ozy' has compared Andrew Undershaft's apparent undermining of Shaw's own personal, general convictions about the 'Life Force', and Shaw's attempt to have Adolphus Cusins restore some philosophical balance.[14] Norma Nutter has briefly discussed conflicts between the character's personal convictions compared to the social realities that they eventually face, via the concept of 'false consciousness'.[15]

Relatedly, several others have looked at the play in relation to the circumstances of the period in which it was written. Bernard Dukore has examined the historical context of the depiction of money in the play, relating the then-contemporary situation with inflation to more recent historical circumstances.[16] Nicholas Williams has discussed possibilities for reinterpretation of the play in a more contemporary context, away from the immediate historical context of its original period.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Albert, Sidney P. (September 2013). "The Time of Major Barbara". "Shaw": "The Journal of Bernard Shaw Studies". 33 (September): 17–24. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-05402-2_75.

- ^ a b Albert, Sidney P. (May 1968). ""In More Ways than One": "Major Barbara"'s Debt to Gilbert Murray". Educational Theatre Journal. 20 (2): 123–140. doi:10.2307/3204896. JSTOR 3204896.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt1489916/?ref_=nv_sr_srsg_1 [user-generated source]

- ^ Albert, Sidney P. (2001). "From Murray's Mother-in-Law to Major Barbara: The Outside Story". Shaw. 22: 19–65. doi:10.1353/shaw.2002.0002. S2CID 159544781. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ Albert, Sidney P. (2014). "Fiction and Fact in Shaw's Account of "Major Barbara"'s Salvation Army Origins". Shaw. 34 (1): 162–175. doi:10.5325/shaw.34.1.0162. JSTOR 10.5325/shaw.34.1.0162. S2CID 191267448.

- ^ Albert, Sidney P. (2013). "The Time of Major Barbara". Shaw. 33 (1): 17–24. doi:10.5325/shaw.33.1.0017. JSTOR 10.5325/shaw.33.1.0017. S2CID 160860271.

- ^ Albert, Sidney P. (1981). "The Lord's Prayer and Major Barbara". Shaw. 1: 107–128. JSTOR 40681060.

- ^ Macintosh, Fiona (1998). "The Shavian Murray and the Euripidean Shaw: Major Barbara and the Bacchae". Classics Ireland. 5: 64–84. doi:10.2307/25528324. JSTOR 25528324.

- ^ Jordan, Robert J (Fall 1970). "Theme and Character in Major Barbara". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 12 (3): 471–480. JSTOR 40754113.

- ^ Frank, Joseph (March 1956). "Major Barbara – Shaw's "Divine Comedy"". PMLA. 71 (1): 61–74. JSTOR 40754113.

- ^ Wisenthal, J.L. (May 1972). "The Underside of Undershaft: A Wagnerian Motif in Major Barbara". The Shaw Review. 15 (2): 56–64. JSTOR 40682274.

- ^ Berst, Charles A (March 1968). "The Devil and Major Barbara". PMLA. 83 (1): 71–79. JSTOR 40754113.

- ^ Everding, Robert G (1983). "Fusion of Character and Setting: Artistic Strategy in Major Barbara". Shaw. 3: 103–116. doi:10.5325/shaw.33.1.0017. JSTOR 10.5325/shaw.33.1.0017. S2CID 160860271.

- ^ Ozy (January 1958). "The Dramatist's Dilemma: an Interpretation of Major Barbara". Bulletin (Shaw Society of America). 2 (4): 18–24. JSTOR 40681527.

- ^ Nutter, Norma (May 1979). "Belief and Reality in Major Barbara". The Shaw Review. 22 (2): 89–91. JSTOR 40682547.

- ^ Dukore, Bernard F. (2016). "How Much?: Understanding Money in Major Barbara". Shaw. 36 (1): 73–81. doi:10.5325/shaw.36.1.0073. JSTOR 10.5325/shaw.36.1.0073. S2CID 156687492.

- ^ Williams, Nicholas (2006). "Shaw Reinterpreted". Shaw. 26: 143–161. doi:10.1353/shaw.2006.0022. JSTOR 40681737. S2CID 201757876.