Dean Mahomed

Sake Dean Mahomed | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Thomas Mann Baynes, c. 1810 | |

| Pronunciation | Sheikh Din Mahomed |

| Born | Din Mahomed c. May 1759 |

| Died | 24 February 1851 (aged 91) |

| Other names |

|

| Notable work | The Travels of Dean Mahomet (1794) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 7 |

Dean Mahomed (1759–1851) was a British Indian traveller, soldier, surgeon, entrepreneur, and one of the most notable early non-European immigrants to the Western World.[1] Due to non-standard transliteration, his name is spelled in various ways. His high social status meant that he later adopted the honorific "Sake" meaning "venerable one".[2] Mahomed introduced Indian cuisine and shampoo baths to Europe, where he offered therapeutic massage.[a] He was also the first Indian to publish a book in English.[3][4]

Early life

[edit]"so long as the Sepoys maintain their formations, which they call 'lines', they are like an immovable volcano spewing artillery and rifle fire like unrelenting hail on the enemy, and they are seldom defeated."

Born c. May 1759 in the city of Patna, then part of the Bengal Subah and today the capital of the Indian state of Bihar.[5] Dean Mahomed described himself as a "native of Patna"[6] belonging to a Shia Muslim family that claimed Arab and Afshar Turk origin.[7][8] However other sources indicate that he belonged to the Nai caste of barbers.[9]

In his work Shampooing, he described himself as a native of India, born in the city of Patna in Hindoostan:[10]

"The humble author of these sheets, is a native of India; and was born in the year 1749, at Patna, the capital of Bihar, in Hindoostan, about 290 miles N.W. of Calcutta. I was educated to the profession of, and served in the Company's Service, as a Surgeon, which capacity I afterwards relinquished, and acted in a military character, exclusively for nearly fifteen years. In … the commencement of the year 1784, [I] left the service and came to Europe, where I have resided ever since."

Dean Mahomed's father served in the Bengal Army which mainly recruited from the area of Bihar and the historian, Michael H. Fisher believes that Dean Mahomed's father was recruited by Robert Clive during a recruitment drive in the town of Buxar.[11] He claimed he had ancestors who worked in administrative service under the Mughal Emperors and the Nawabs of Murshidabad.[12] Sake Dean Mahomed grew up in Patna and his father died in battle when Mahomed was about 11 years old.[8]

Following his father's death, he was taken under the wing of Captain Godfrey Evan Baker, an Anglo-Irish Protestant officer. Mahomed served in the army of the East India Company as a trainee surgeon and against the Marathas. He remained with Captain Baker until 1782 when the Captain resigned. That same year, Mahomed also resigned from the Army, choosing to accompany Baker, 'his best friend', to Ireland.[13]

Adult life and family

[edit]In 1784, Mahomed emigrated to Cork, Ireland, with the Baker family.[13] There he studied to improve his English language skills at a local school, and fell in love with Jane Daly, a "pretty Irish girl of respectable parentage". The Daly family was opposed to their relationship because it was illegal for Protestants to marry non-Protestants at the time, so the couple eloped to another town to get married.[14][13][15] Mahomed and Daly were married in the Diocese of Cork & Ross in Cork.[16][17] They moved to 7 Little Ryder Street in London, England, at the turn of the 19th century."[18][19] In 1786, Mahomed converted from Islam to Christianity.[20][21][22]

According to leading scholars, and as indicated by parish records in London, Mahomed contracted a bigamous marriage in Marylebone in 1806 to Jane Jeffreys (1780-1850); the banns were read on 24 August for Jane and "William Mahomet."[23][24] He had a daughter, Amelia (b. 1808) by her and is listed as the father "William Dean Mahomet" in the parish register.[25][26] Amelia was baptised on 11 June 1809 at St Marylebone, Westminster, in London.[26] By his legal wife, Sake Dean Mahomed had seven children: Rosanna, Henry, Horatio, Frederick, Arthur,[15] and Dean Mahomed (baptised in the Roman Catholic church of St. Finbarr's, Cork, in 1791).[27]

His son, Frederick, was the proprietor of Medicated and Hot and Cold Baths at Brighton[b][28] and also ran a boxing and fencing academy near Brighton. His most famous grandson, Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (c. 1849–1884), became an internationally known physician[15] and worked at Guy's Hospital in London. In 1869, he opened a "Turkish bath room" in Somerset Street, London.[29] In 1863 he added a Victorian Turkish bath to his establishment which remained open till the early 1870s. He made important contributions to the study of high blood pressure.[30] Another of Sake Dean Mahomed's grandsons, Rev. James Keriman Mahomed, was appointed as the vicar of Hove, Sussex, in the late 19th century.[15] James married Emma Louisa Black, a flower painter whose work was displayed at the Royal Academy.[31] Together they had a son, RAF Captain Felix Wyatt. Felix was killed in action during the First World War after he was shot down whilst flying over France.[31] During the war, Frederick and James' children changed their surnames from Mahomed to Deane and Wyatt, respectively, in order to avoid xenophobic attention at a time when racial prejudice was rife and mixed marriages were disapproved of.[31][32]

The Travels of Dean Mahomet

[edit]

On 15 January 1794, Mahomed published a book titled The Travels of Dean Mahomet. The book is in epistolary form as was common for travel books and many novels in that era and consists of 38 letters.[33] The book begins with a brief introduction where he contrasts Ireland and India, writing that "the face of every thing about me [is] so contrasted to those striking scenes in India."[34] and proceeds to give a sketch of his early years. He then describes his travels over the period 1770 to 1775 as a camp follower to the Bengal army as it moved around North East India. A series of military conflicts are described along with descriptions of some major cities, including Kolkata (Calcutta) and Varanasi (Benares). This is accompanied by first hand accounts of Indian culture, trade, military conflicts, food, wildlife, etc.[35] The book concludes with a description of Mahomed's voyage to Britain where he arrived at Dartmouth in September 1784. While Mahomed gives an insightful and sympathetic account of India and Indian customs, as Mona Narain points out this is done from an essentially European cultural perspective - he consistently uses the pronoun "we" to describe himself and Europeans, and does not in his writings seek to challenge poor governmental management within the East India Company.[36] The historian Michael Fisher, who published a biographical essay to accompany an edition of the book, suggested that some passages in the book were closely paraphrased from other travel narratives written in the late 18th century.[37]

Restaurant venture

[edit]

In 1810, after moving to London, Sake Dean Mahomed opened the first Indian restaurant in England: the Hindoostane Coffee House in George Street, near Portman Square, Central London.[38] The restaurant offered, among other items, hookah "with real chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes, ... allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England."[39] The restaurant also provided a home delivery service.[2] This venture came to an end in 1812 due to financial difficulties.[25]

Introduction of shampooing to Europe

[edit]Before opening his restaurant, Mahomed had worked in London for nabob Basil Cochrane, who had installed a steam bath for public use in his house in Portman Square and promoted its medical benefits. Once again indicating his acceptance by the wealthy elite, Mahomed and his family lived alongside the rich and titled in Portman Square and Mahomed may have been responsible for introducing the practice of "champi" or "shampooing" (or Indian massage) there.[2] In 1814, Mahomed and his family moved back to Brighton and opened the first commercial "shampooing" vapour masseur bath in England, "Mahomed's Baths", on the site now occupied by the Queen's Hotel. Located on the seafront, the luxurious bathhouse offered therapeutic baths and shampooing with Indian oils.[2] He described the treatment in a local paper as "The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath, a cure to many diseases and giving full relief when every thing fails; particularly Rheumatic and paralytic, gout, stiff joints, old sprains, lame legs, aches and pains in the joints".[40] Jane Daly, Mahomed's wife, was also actively involved in the bathhouse business. Adverts suggested that, like her husband, Jane possessed "the art of shampooing" and that she superintended the Ladies Baths.[2] The business was an immediate success and Dean Mahomed became known as "Dr. Brighton". Hospitals referred patients to him and he was appointed as shampooing surgeon to both King George IV and William IV.[40] Due to a lack of capital, however, Mahomed's Baths was put up for auction in the late 1830s and Mahomed and his family were forced to relocate to more modest accommodation in Brighton.[2]

The literary critic Muneeza Shamsie notes that Mahomed wrote two books connected to his burgeoning trade.[40] The first was Cases Cured by Sake Deen Mahomed, Shampooing Surgeon, and Inventor of the Indian Medicated Vapour and Sea-Water Bath (1820), while the second, Shampooing; or, benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath, went through three editions (1822, 1826, 1838) and was dedicated to King George IV.[41][24] In this work, Mahomed speaks of the initial resistance to the idea of shampooing among the English he encountered in his new country: "It is not in the power of any individual to give unqualified satisfaction, or to attempt to establish a new opinion without the risk of incurring the ridicule, as well as censure, of some portion of mankind. So it was with me: in the face of indisputable evidence, I had to struggle with doubts and objections raised and circulated against my Bath, which, but for the repeated and numerous cures effected by it, would long since have shared the common fate of most innovations in science."[42]

Death

[edit]

Mahomed died on 24 February 1851 (aged 91–92) at 32 Grand Parade, Brighton. He was buried in a grave at St Nicholas Church, Brighton, in which his son Frederick was later interred. Frederick taught fencing, gymnastics and other activities in Brighton at a gymnasium he built on the town's Church Street.[43]

Recognition

[edit]After his death in 1851, Sake Dean Mahomed, once so renowned in Ireland and Brighton's social scenes, began to lose prominence as a public figure and until the scholarly interventions of the last fifty years was largely forgotten by history.[2] The modern renewal of interest in his writings developed after poet and scholar Alamgir Hashmi drew attention to him in the 1970s and 1980s. Michael H. Fisher has written a book on Mahomet entitled The First Indian Author in English: Dean Mahomed in India, Ireland, and England (Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1996). Additionally, Rozina Visram's Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947 (1998) was highly influential in drawing public attention to Mahomed's life and work.[44]

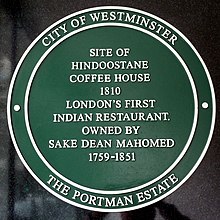

Several commemorations of and tributes to Mahomed's legacy have taken place in the 21st century. On 29 September 2005 the City of Westminster unveiled a Green Plaque commemorating the opening of the Hindoostane Coffee House.[38] The plaque is at 102 George Street, close to the original site of the coffee house at 34 George Street.[45] On 15 January 2019, Google recognised Sake Dean Mahomed with a Google Doodle on the main page.[46]

Excerpts from Dean Mahomed's writings were included in the anthology, The Book of Bihari Literature, which was edited by the diplomat, Abhay Kumar to celebrate literature which has come from people born in the state of Bihar.[47][48]

See also

[edit]Published works

[edit]- The Travels of Dean Mahomet, a Native of Patna in Bengal, Through Several Parts of India, While in the Service of the Honourable the East India Company. Cork: J. Connor. 1794.

- Fisher, Michael Herbert, ed. (1997). The Travels of Dean Mahomet: An Eighteenth-Century Journey Through India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20717-2.

- Shampooing; or, benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath. Brighton: Creasy & Baker. 1823.

- Shampooing; or, Benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath (3rd ed.). Bath: Wm. Fleet. 1838.

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The word "shampoo" did not take on its modern meaning of washing the hair until the 1860s. See p. 197 in The travels of Dean Mahomet, and "shampoo", v., entry, p. 167, Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., vol. 15, ISBN 0-19-861227-3.

- ^ The Domestic Encyclopædia, published in 1802, defines medicated baths as "those saturated with various mineral, vegetable, or sometimes animal substances. Thus we have sulphur and steel baths, aromatic and milk baths;—there can be no doubt, that such ingredients, if duly mixed, and a proper temperature be given to the water, may, in certain complaints, be productive of effects highly beneficial."

Citations

[edit]- ^ Mahomet 1794, pp. 148–149, 155–156, 160.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Sake Dean Mahomed and Jane Daly". The Mixed Museum. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ Fisher 2000.

- ^ "Sake Dean Mahomed, The first Indian to publish a book in English". Devdiscourse News. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 17. Britain, the Netherlands and Scandinavia (1800-1914). Brill. 2020. ISBN 9789004442399.

- ^ Narain, Mona (2009). "Dean Mahomet's "Travels", Border Crossings, and the Narrative of Alterity". Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. 49 (3): 693–716. doi:10.1353/sel.0.0070. JSTOR 40467318. S2CID 162301711.

- ^ Fisher, Michael (2004). "Mahomed, Deen [formerly Deen Mahomet]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53351. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Mahomet 1997.

- ^ "Sake Dean Mahomed (1759-1851), Shampooing surgeon, restaurateur and author Sake Dean Mahomed (Deen Mahomed (né Mahomet)". National Portrait Gallery.

- ^ Fisher, Michael. "Early Asian Travelers to the West: Indians in Britain, c.1600–c.1850". World History Connected.

- ^ Fisher, Michael (1996). The First Indian Author in English: Dean Mahomed (1759-1851) in India, Ireland, and England. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780195638998.

- ^ Das 2016, pp. 199–211.

- ^ a b c Husainy, Abi (6 November 2013). "Dean Mahomed's Early Life in India". Moving Here: Tracing Your Roots. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ "5 Fast Facts About Sake Dean Mahomed". 15 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d Ansari 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Platt, Lyman (1999). "Irish Records Extraction Database". Ancestry.com.

- ^ Mahomet 1997, Ch. 3 Dean Mahomet in Ireland and England (1784–1851).

- ^ Ansari 2004, p. 57–58.

- ^ "London, England, City Directories, 1736-1943". ancestry.com. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ^ Kathleen, Wilson (2004). A New Imperial History: Culture, Identity and Modernity in Britain and the Empire, 1660-1840. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 9780521007962.

Others , like Dean Mahomed , became Christian but retained an explicitly non-Christian name.

- ^ Yazdani, Kaveh (2017). India, Modernity and the Great Divergence: Mysore and Gujarat (17th to 19th C.). BRILL. p. 72. ISBN 9789004330795.

Dean Mahomet (1759–1851), a Muslim who converted to Anglican Christianity.

- ^ A. Chesworth, John (2020). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 17. Britain, the Netherlands and Scandinavia (1800-1914). BRILL. p. 91. ISBN 9789004442399.

He emigrated with Baker to the latter's hometown of Cork, Ireland, where he converted to Anglican Christianity.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: p89/mry1/288. Ancestry.com. London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Church of England Parish Registers. London Metropolitan Archives, London.

- ^ a b Fisher 2014, p. 128.

- ^ a b Husainy, Abi (7 November 2013). "Dean Mahomed in London". Moving Here: Tracing Your Roots. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ a b London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812; Reference Number: P89/MRY1/084. Ancestry.com. London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812. London, England: London Metropolitan Archives.

- ^ "Dean Mahomed baptism". Irish Genealogy. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ "Mahomed, Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar". Royal College of Physicians. 24 May 2005. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- ^ '[Advertisement]'. The Times. (30 January 1860). p.3

- ^ O'Rourke 1992, pp. 212–213.

- ^ a b c "Sake Dean Mahomed and Jane Daly". The Mixed Museum. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Cameron, J. Stewart; Hicks, Jackie; Carl, Gottschalk (1 May 1996). "Frederick Akbar Mahomed and his role in the description of hypertension at Guy's Hospital". Kidney International. 49 (5): 1488–1506. doi:10.1038/ki.1996.209. ISSN 0085-2538. PMID 8731118.

- ^ Fisher, Michael H. (1998). "Representations of India, the English East India Company, and Self by an Eighteenth-Century Indian Emigrant to Britain". Modern Asian Studies. 32 (4): 891–911. doi:10.1017/S0026749X9800314X. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 313054. S2CID 145623856.

- ^ Mahomet 1794, Letter I: when I first came to Ireland, I found the face of every thing about me so contrasted to those striking scenes in India

- ^ Mahomet 1794.

- ^ Narain, Mona (2009). "Dean Mahomet's "Travels", Border Crossings, and the Narrative of Alterity". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 49 (3): 693–716. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 40467318.

- ^ Fisher 1998 p. 138-140.

- ^ a b "Curry house founder is honoured". BBC News. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Husainy, Abi. "Dean Mahomed in London".

- ^ a b c Teltscher 2000, pp. 409–423.

- ^ Mahomed 1838, p. iii.

- ^ Mahomed 1838, p. vii.

- ^ Collis 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Zarr, Gerald (March 2018). "The Shampooing Surgeon of Brighton". Aramco World.

- ^ "Westminster Green Plaques" (PDF). City of Westminster. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- ^ "Celebrating Sake Dean Mahomed". google.com.

- ^ Kumar, Abhay (2022). The Book Of Bihari Literature. HarperCollins. pp. 20–25. ISBN 9789356291508.

- ^ Ray, Jonaki (18 January 2023). "Review of The Book of Bihari Literature". Financial Express.

Sources

[edit]- Ansari, Humayun (2004). The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-685-2.

- Collis, Rose (2010). The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. (based on the original by Tim Carder) (1st ed.). Brighton: Brighton & Hove Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9564664-0-2.

- Das, Alok (2016). "Life and Legacy of Sake Dean Mahomet: A Forgotten Enigma". Communication Studies and Language Pedagogy. 2 (1–2): 199–211.

- Fisher, Michael H. (2000). The First Indian Author in English: Dean Mahomed (1759-1851) in India, Ireland, and England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195638998.

- Fisher, Michael H. (2014). "South Asians in Britain up to the 1850s". In Chatterji, Joya; Washbrook, David (eds.). 'Routledge Handbook of the South Asian Diaspora. Routledge.

- O'Rourke, Michael F. (1992). "Frederick Akbar Mahomed". Hypertension. 19 (2): 212–217. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.19.2.212. PMID 1737655.

- Teltscher, Kate (2000). "The Shampooing Surgeon and the Persian Prince: Two Indians in Early Nineteenth-century Britain". Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. 2 (3): 409–23. doi:10.1080/13698010020019226. S2CID 161906676.

External links

[edit]- Celebrating Sake Dean Mahomed at Google Doodle

- Web version of The Travels of Dean Mahomet

- Works by or about Sake Dean Mahomed at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Sake Dean Mahomed at HathiTrust

- Plaque #3165 on Open Plaques. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Making History – Sake Dean Mahomed – Regency 'Shampooing Surgeon'", BBC – Beyond the Broadcast

- Black History in Brighton

- Portraits of Dean Mahomed at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Differences in Attitudes: Sheikh Deen Mahomed and Shampoo (Urdu)

- 1759 births

- 1851 deaths

- 18th-century Indian writers

- 19th-century Indian writers

- British Anglicans

- British former Shia Muslims

- Converts to Anglicanism from Shia Islam

- Indian Anglicans

- Indian emigrants to England

- Writers from Bihar

- Indian former Shia Muslims

- Indian surgeons

- Indian travel writers

- Writers from Patna

- British East India Company Army officers

- 18th-century surgeons

- 19th-century surgeons

- 18th-century travel writers

- 19th-century travel writers

- 18th-century male writers

- 19th-century male writers

- Writers from British India

- Medical doctors from British India