Capital punishment in Judaism

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

Capital punishment in traditional Jewish law has been defined in Codes of Jewish law dating back to medieval times, based on a system of oral laws contained in the Babylonian and Jerusalem Talmud, the primary source being the Hebrew Bible. In traditional Jewish law there are four types of capital punishment: a) stoning, b) burning by ingesting molten lead, c) strangling, and d) beheading, each being the punishment for specific offenses. Except in special cases where a king can issue the death penalty, capital punishment in Jewish law cannot be decreed upon a person unless there were a minimum of twenty-three judges (Sanhedrin) adjudicating in that person's trial who, by a majority vote, gave the death sentence, and where there had been at least two competent witnesses who testified before the court that they had seen the litigant commit the offense. Even so, capital punishment does not begin in Jewish law until the court adjudicating in this case had issued the death sentence from a specific place (formerly, the Chamber of Hewn Stone) on the Temple Mount in the city of Jerusalem.[1]

History

[edit]Capital and corporal punishment in Judaism have a complex history which has been a subject of extensive debate. The Bible and the Talmud specify capital punishment by the "Four Executions of the Court," — stoning, burning, decapitation, and strangulation — for the most severe transgressions,[2] and the corporal punishment of flagellation for intentional transgressions of negative commandments that do not incur one of the Four Executions. According to Talmudic law, the authority to apply capital punishment ceased with the destruction of the Second Temple.[2][3] The Mishnah states that a Sanhedrin that executes one person in seven years — or seventy years, according to Eleazar ben Azariah — is considered bloodthirsty.[4][5] During the Late Antiquity, the tendency of not applying the death penalty at all became predominant in Jewish courts.[6] In practice, where medieval Jewish courts had the power to pass and execute death sentences, they continued to do so for particularly grave offenses, although not necessarily the ones defined by the law.[2] While it was recognized that the use of capital punishment in the post-Second Temple era went beyond the biblical warrant, the rabbis who supported it believed that it could be justified by other considerations of Jewish law.[7][8] Whether Jewish communities ever practiced capital punishment according to rabbinical law, and whether the rabbis of the Talmudic era ever supported its use even in theory, has been a subject of historical and ideological debate.[9]

The 12th-century Jewish legal scholar Maimonides stated that "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death."[10] Maimonides argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until convictions would be mere "according to the judge's caprice". Maimonides was concerned about the need for the law to guard itself in public perception, to preserve its majesty, and to retain the people's respect.[11]

The position of Jewish Law on capital punishment often formed the basis of deliberations by Israel's Supreme Court. It has been carried out by Israel's judicial system only twice, in the cases of Adolf Eichmann[8] and Meir Tobianski.

Capital punishment in classical sources

[edit]In the Pentateuch

[edit]

The institution of capital punishment in Jewish law is defined in the Law of Moses (Torah) in multiple places. The Mosaic Law provides for the death penalty to be inflicted upon those persons convicted of the following offenses:

- adultery (for a married woman and her lover)[12][13]

- bestiality[14]

- blasphemy[15]

- child sacrifice[16]

- false testimony in capital cases[17]

- false prophecy[18]

- proselytizing and promoting other religions[19]

- male homosexual relations[20]

- idolatry, actual or virtual[21]

- incestuous relations[22]

- insubordination to supreme authority[23]

- lying about one's virginity upon marrying a spouse (Deuteronomy 22:13–21)[13][24]

- kidnapping[25]

- licentiousness of a priest's daughter[26]

- murder[27]

- rape committed against a betrothed woman[28]

- striking, cursing, or otherwise rebelling against parental authority[29]

- Sabbath-breaking[30]

- touching Mount Sinai while God was giving Moses the Ten Commandments[31]

- witchcraft, divination, necromancy, sorcery, etc.[32][33]

In Rabbinic Judaism

[edit]

The principal tractate in the Talmud that deals with such cases is Tractate Sanhedrin.

Cases concerning offenses punishable by death are decided by 23 judges.[34] The reason for this odd number is that the early rabbis had learnt that it takes at least 10 judges to convict a man, and another 10 judges to acquit a man, and the court being unequal will result in a verdict rendered by majority vote.[35] Strict regulations were in place as to how these judges were to be selected, based on their sex, age and family standing. For example, they could not appoint a judge who did not have children of his own, for he was thought to be less merciful towards other men's children.[36] Neither could they select a judge who was not a male, by way of an edict,[37][38] and which others say was because of the levity and temerity of the other sex.[39] Nor could they admit the testimony of women in a court of Jewish law where the death-penalty hinged over the accused.[40][41][42][43]

The harshness of the death penalty indicated the seriousness of the crime. Jewish philosophers argue that the whole point of corporal punishment was to serve as a reminder to the community of the severe nature of certain acts. This is why, in Jewish law, the death penalty is more of a principle than a practice. The numerous references to the death penalty in the Torah underscore the severity of the sin, rather than the expectation of death. This is bolstered by the standards of proof required for application of the death penalty, which were extremely stringent.[44] The Mishnah outlines the views of several prominent first-century CE rabbis on the subject:

"A Sanhedrin that puts a man to death once in seven years is called a murderous one. Rabbi Eliezer ben Azariah said, 'Or even once in 70 years.' Rabbi Tarfon and Rabbi Akiba said, 'If we had been in the Sanhedrin, no death sentence would ever have been passed'; Rabban Simeon ben Gamaliel said, 'If so, they would have multiplied murderers in Israel.'"[45][46]

The Talmud notes that "forty years before the destruction of the [Second] Temple, capital punishment ceased in Israel."[47] This date is traditionally put at 28 CE, a time that corresponds with the 18th year of Tiberius' reign. At this time, the Sanhedrin required the approbation of the Roman procurator of Judea before they could punish any malefactor by death. Other sources, such as Josephus, disagree. The issue is highly debated because of its relevance to the New Testament trial of Jesus.[48][49] Ancient rabbis did not like the idea of capital punishment, and interpreted the texts in a way that made the death penalty virtually non-existent.

Legal proceedings involving capital punishment were to be handled with extreme caution. In all cases of capital punishment in Jewish law, the judges are required to open their deliberations by pointing out the good qualities of the litigant and to bring up arguments about why he should be acquitted.[50][51] Only later did they hear the incriminating evidence. It was almost impossible to inflict the death penalty because the standards of proof were so high. As a result, convictions for capital offenses were rare, but did happen in Judaism.[52][53][54] The standards of evidence in capital cases include:

- Two witnesses were required. Acceptability was limited to:

- Adult Jewish men who were known to keep the commandments knew the written and oral law, and had legitimate professions;

- The witnesses had to see each other at the time of the sin;

- The witnesses had to be able to speak clearly, without any speech impediment or hearing deficit (to ensure that the warning and the response were done);

- The witnesses could not be related to each other, or to the accused.

- The witnesses had to see each other, and both of them had to give a warning (hatra'ah) to the person that the sin they were about to commit was a capital offense;[55]

- This warning had to be delivered within seconds of the performance of the sin (in the time it took to say, "Peace unto you, my Rabbi and my Master");

- In the same amount of time, the person about to sin had to both respond that s/he was familiar with the punishment, but they were going to sin anyway; and begin to commit the sin/crime;

- However, if the accused has already committed the crime, the accused would have been given a chance to repent (i.e. Ezekiel 18:27), and if they repeated the same crime, or any other, it would lead to a death sentence. If witnesses were caught lying about the crime, they would be executed.

- The Beth Din (rabbinical court) had to examine each witness separately; and if even one minor point of their evidence, such as eye color, was contradictory the evidence was considered contradictory, and the evidence was not heeded;

- The Beth Din had to consist of a minimum of 23 judges;

- The majority could not be a simple majority - the split verdict that would allow conviction had to be at least 13 to 10 in favor of conviction;

- If Beth Din arrived at a unanimous verdict of guilty, the person was let go - the idea being that if no judge could find anything exculpatory about the accused, there was something wrong with the court.[56]

- The witnesses were appointed by the court to be the executioners.

Where the death sentence was warranted but the court did not the jurisdiction to mete out the death sentence, such as when there were not two or more witnesses, the court had the authority to lock up the convicted individual within a cupola, or similar confined structure, and to feed them meager portions of bread and water until they died.[57]

Megillat Taanit

[edit]According to an oral teaching appearing in Megillat Taanit, the four modes of execution formerly used in Jewish law were mostly orally transmitted practices not explicitly stated in the Written Law of Moses, although some modes of punishment are explicitly stated. Megillat Taanit records that "On the fourth[a] [day] of [the lunar month] Tammuz, the book of decrees had been purged (עדא ספר גזרתא)". The Hebrew commentary (scholion) on this line brings two different explanations of this event; according to one of the explanations, the "book of decrees" was composed by the Sadducees and used by them as proof concerning the four modes of capital punishment; the Pharisees and rabbis preferred to determine the punishments via orally transmitted interpretation of scripture.[58]

Modes of punishment

[edit]

The court had the power to inflict four kinds of death penalty: stoning, burning, beheading, and strangling.[59]

For some crimes, the Bible specifies which form of execution is to be used. Blasphemy, idolatry, Sabbath-breaking, witchcraft, prostitution by a betrothed virgin, or deceiving her husband at marriage as to her chastity (Deut. 22:21), and the rebellious son are punished with death by stoning; bigamous marriage with a wife's mother and the prostitution of a priest's daughter is punished by burning; communal apostasy is punished by the sword.

With reference to all other capital offenses, the law ordains that the perpetrator shall die a violent death, occasionally adding the expression, "His (their) blood shall be upon him (them)." This expression applies to death by stoning.

The Bible speaks also of hanging (Deut. 21:22), but (according to the rabbinical interpretation) not as a mode of execution, but rather of exposure after death.[60][61]

The following is a list by Maimonides of the crimes punished by each form of capital punishment:[62]

Punishment by stoning

[edit]

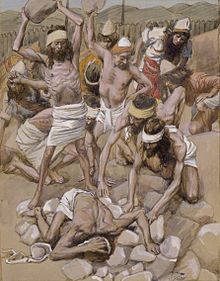

Death by stoning (סקילה, skila) was issued for the transgression of one of eighteen crimes, among which being those who wantonly transgressed the Sabbath day by breaking its laws (excluding those who may have broken the Sabbath laws unintentionally), as well as a male who had a licentious connection with another male.[63] Stoning was administered by throwing the condemned person off a height, typically twice the height of an average person, so that they would fall to the ground. If the fall did not result in death, a large stone would be dropped on the person's chest. If this still did not cause death, bystanders would then continue to hurl stones until the person was dead.[64]

- Intercourse between a man and his mother.

- Intercourse between a man and his father's wife (not necessarily his mother).

- Intercourse between a man and his daughter-in-law.

- Intercourse with another man's wife from the first stage of marriage.

- Intercourse between two men.

- Bestiality.

- Cursing the name of God in God's name.

- Idol worship.

- Giving one's progeny to Molech (child sacrifice).

- Necromancy sorcery.

- Pythonic sorcery.

- Attempting to convince another to worship idols.

- Instigating a community to worship idols.

- Witchcraft.

- Violating the Sabbath.

- Cursing one's own parent.

- Ben sorer umoreh, a stubborn and rebellious son.

Punishment by burning

[edit]Death by burning (שריפה, serefah) was issued for ten offenses, including prostitution and bigamous relations with one's wife and their mother.[63] Perpetrators were not burnt at the stake, but rather molten lead was poured down the perpetrator's esophagus. Alternatively, the burning was inflicted after the perpetrator had been stoned, a precedent that was established in Achan's stoning.[65]

According to Halakha, this punishment is conducted by pouring molten metal (lead, or a mixture of lead and tin) into one's throat, rather than burning at the stake.

- The daughter of a priest who completed the second stage of marriage commits adultery.

- Intercourse between a man and his daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his daughter's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his son's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his wife's daughter (not necessarily his own daughter).

- Intercourse between a man and his wife's daughter's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his wife's son's daughter.

- Intercourse between a man and his mother-in-law.

- Intercourse between a man and his mother-in-law's mother.

- Intercourse between a man and his father-in-law's mother.

Punishment by the sword

[edit]Death by the sword (הרג, hereg) was issued in two cases: for wanton murder and for communal apostasy (idolatry). The perpetrators of these crimes were beheaded.[63]

- Unlawful premeditated murder.

- Being a citizen of an Ir nidachat, a "city that has gone astray".

Punishment by strangulation

[edit]Death by strangulation (חנק, chenek) was issued for six crimes, among which being a man who had a forbidden connection with another man's wife (adultery), and a person who willfully caused injury (bruise) to one of his/her parents.[61]

- Committing adultery with another man's wife, when it does not fall under the above criteria.

- Wounding one's own parent.

- Kidnapping another Israelite.

- Prophesying falsely.

- Prophesying in the name of other deities.

- A sage who is guilty of insubordination in front of the grand court in the Chamber of the Hewn Stone.

Contemporary attitudes towards capital punishment

[edit]Rabbinical courts have given up the ability to inflict any kind of physical punishment, and such punishments are left to the civil court system to administer. The modern institution of the death penalty, at least as practiced in the United States, is opposed by the major rabbinical organizations of Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Judaism.[66][67] In a 2014 poll, 57 percent of Jews surveyed said they supported life in prison without the chance of parole over the death penalty for people convicted of murder.[68]

Orthodox Judaism

[edit]Orthodox Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan wrote:

"In practice, ... these punishments were almost never invoked, and existed mainly as a deterrent and to indicate the seriousness of the sins for which they were prescribed. The rules of evidence and other safeguards that the Torah provides to protect the accused made it all but impossible to actually invoke these penalties ... the system of judicial punishments could become brutal and barbaric unless administered in an atmosphere of the highest morality and piety. When these standards declined among the Jewish people, the Sanhedrin ... voluntarily abolished this system of penalties.[69]

On the other hand, Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, in a letter to then-New York Governor Hugh Carey, states: "One who murders because the prohibition to kill is meaningless to him, and he is especially cruel, and so too when murderers and evil people proliferate, they [the courts] would [should?] judge [capital punishment] to repair the issue [and] to prevent murder – for this [action of the court] saves the state."[70]

According to Yaakov Elman, imprisonment of criminals was impractically expensive under the material conditions of ancient society, which meant that the death penalty and other corporal punishments were the only available options for severe crimes. Thus, use of the death penalty in ancient society would not necessarily imply that the Jewish tradition prefers it in wealthy modern society.[71]

Conservative Judaism

[edit]In Conservative Judaism, the death penalty was the subject of a responsum by its Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, which has gone on record as opposing the modern institution of the death penalty:

"The Talmud ruled out the admissibility of circumstantial evidence in cases which involved a capital crime. Two witnesses were required to testify that they saw the action with their own eyes. A man could not be found guilty of a capital crime through his own confession or through the testimony of immediate members of his family. The rabbis demanded a condition of cool premeditation in the act of crime before they would sanction the death penalty; the specific test on which they insisted was that the criminal be warned prior to the crime, and that the criminal indicate by responding to the warning, that he is fully aware of his deed, but that he is determined to go through with it. In effect, this did away with the application of the death penalty. The rabbis were aware of this, and they declared openly that they found capital punishment repugnant to them… There is another reason which argues for the abolition of capital punishment. It is the fact of human fallibility. Too often, we learn of people who were convicted of crimes, and only later are new facts uncovered by which their innocence is established. The doors of the jail can be opened; in such cases, we can partially undo the injustice. But the dead cannot be brought back to life again. We regard all forms of capital punishment as barbaric and obsolete."[72]

Reform Judaism

[edit]Since 1959, the Central Conference of American Rabbis and the Union for Reform Judaism have formally opposed the death penalty. The Central Conference also resolved in 1979 that "both in concept and in practice, Jewish tradition found capital punishment repugnant", and there is no persuasive evidence "that capital punishment serves as a deterrent to crime".[73]

Humanistic Judaism

[edit]Humanistic Judaism has no policy on the use of the death penalty.[74]

See also

[edit]- Capital punishment in Israel

- Death penalty in the Bible

- List of capital crimes in the Torah

- Religion and capital punishment

- Testimony in Jewish law

Notes

[edit]- ^ Following Vered Noam, Megillat Taanit – The Scroll of Fasting; variant manuscripts say 10th or 14th day

References

[edit]- ^ Jerusalem Talmud (Horayot 2a): "They do not make a person liable until such instruction comes forth from the Chamber of Hewn Stone. Said Rabbi Yohanan: The reason being is that there is a teaching that [explicitly] states, 'From that place which the Lord shall choose' (Deuteronomy 17:10)." Cf. Babylonian Talmud (Rosh Hashanah 31a–b; Avodah Zarah 8b), where the Sanhedrin intentionally removed themselves from the Chamber of Hewn Stone (לשכת הגזית) on the Temple Mount and sat in the Hanuth, and thence removed themselves to other places (known as the ten migratory journeys of the Sanhedrin) so that the court could not execute an offending Jew, since the 23 judges needed to condemn a man to die would formerly convene in the Temple Mount to decide on capital cases.

- ^ a b c Haim Hermann Cohn (2008). "Capital Punishment. In the Bible & Talmudic Law". Encyclopedia Judaica. The Gale Group.

- ^ "[A]t a time when there is no priest [serving in the Temple], there is no judgment [of capital cases]." Sanh. 52b.

- ^ Louis Isaac Rabinowitz (2008). "Capital Punishment. In Practice in the Talmud". Encyclopedia Judaica. The Gale Group.

Similarly, the passage in Mishnah Makkot 1:10: "A Sanhedrin that puts a man to death once in seven years is called a murderous one. R. Eleazar ben Azariah says, 'Or even once in 70 years.' R. Tarfon and R. Akiva said, 'If we had been in the Sanhedrin, no death sentence would ever have been passed'; Rabban Simeon b. Gamaliel said: 'If so, they would have multiplied murderers in Israel.'

- ^ Menachem Elon (2008). "Capital Punishment. In the State of Israel". Encyclopedia Judaica. The Gale Group.

This refers to the statement in the Mishnah (Mak. 1:10; Mak. 7a) that a Sanhedrin that kills (gives the death penalty) once in seven years (R. Eleazer b. Azariah said: once in 70 years) is called "bloody" (ḥovlanit, the term "ḥovel" generally implying a type of injury in which there is blood).

- ^ Glen Warren Bowersock; Peter Brown; Oleg Grabar (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- ^ Dale S. Recinella (2015). The Biblical Truth about America's Death Penalty. Northeastern University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-55553-862-0.

- ^ a b Menachem Elon (2008). "Capital Punishment. In the State of Israel". Encyclopedia Judaica. The Gale Group.

- ^ Jacobs, Jill (2009). There Shall Be No Needy: Pursuing Social Justice Through Jewish Law & Tradition. Woodstock, Vt: Jewish Lights. p. 200. ISBN 978-1-58023-425-2.

- ^ Goldstein, Warren (2006). Defending the human spirit: Jewish law's vision for a moral society. Feldheim Publishers. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-58330-732-8. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ^ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269-271 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ^ Leviticus 20:10;Deuteronomy 22:22

- ^ a b Weren, Wim J. C. (2012). "The Use of Violence in Punishing Adultery in Biblical Texts (Deuteronomy 22:13-29 and John 7:53-8:11)". In Villiers, Pieter G. R. de; Henten, Jan Willem van (eds.). Coping with Violence in the New Testament. BRILL. pp. 134–139. ISBN 978-90-04-22104-8.

- ^ Exodus 22:18; Leviticus 20:15

- ^ Leviticus 24:16

- ^ Leviticus 20:1–3

- ^ Deuteronomy 19:16–19

- ^ Deuteronomy 13:6, Deuteronomy 18:20

- ^ Deuteronomy 13:7–12

- ^ Leviticus 18:22, Leviticus 20:13

- ^ Leviticus 20:2, Deuteronomy 13:7–19, Deuteronomy 17:2–7

- ^ Leviticus 18:22, Leviticus 20:11–14

- ^ Deuteronomy 17:12

- ^ Gane, Roy (2001). "Old Testament Principles Relating to Divorce and Remarriage". Journal of the Adventist Theological Society: 44–45.

- ^ Exodus 21:16, Deuteronomy 24:7

- ^ Leviticus 21:9

- ^ Exodus 21:12, Leviticus 24:17, Numbers 35:16, et seq.

- ^ Deuteronomy 22:25–27

- ^ Exodus 21:15, 17, Leviticus 20:9,Deuteronomy 21:18–21

- ^ Exodus 31:14, Exodus 35:2, Numbers 15:32–36

- ^ Exodus 19:13

- ^ Exodus 22:17, Leviticus 20:27

- ^ Marcus Jastrow, Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. Capital Punishment

- ^ Mishnah Sanhedrin 1:4

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin 2a-b)

- ^ Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Sanhedrin 2:3)

- ^ Maimonides, Mishne Torah (Hil. Melakhim u'milḥamot 1:6 [5])

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Special Laws (Book III, chapter XXXI (169–170)

- ^ Josephus (Antiquities IV.219; Against Apion 2.201)

- ^ Sifrei on Deuteronomy 19:15

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Shevu'ot 30a, Rashi, s.v. בעדים הכתוב מדבר); Jerusalem Talmud (Sanhedrin 3:9)

- ^ Maimonides, Mishneh Torah (Hil. 'Edut 9:2)

- ^ Joseph Karo, Shulhan Arukh (Hoshen Mishpat, Hil. Edut 7:4; 35:14)

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Makkoth 7b

- ^ Mishna, Makkoth 1:10

- ^ Encyclopaedia Judaica. "Capital Punishment". The Gale Group. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Avodah Zarah 8b; Shabbat 15a); Jerusalem Talmud (Sanhedrin 1:1 [1b])

- ^ "Capital Punishment". www. Jewish virtual library. org.

- ^ Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard, eds. (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. p. 795. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- ^ Meiri (2006). Daniel Bitton (ed.). Beit HaBechirah (Chiddushei ha-Meiri) (in Hebrew). Vol. 7. Jerusalem: Hamaor Institute. p. 62. OCLC 181631040., s.v. Sanhedrin 32b, explaining Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:1

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 7. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. pp. 26 [13b], 32 [16b] (Hil. Sanhedrin 9:1, 12:3). OCLC 122758200.

- ^ Mishnah Maccot, 1:10

- ^ "讚讬谞讬 谞驻砖讜转". cet.ac.il.

- ^ |Source= ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 4 |Section= capital punishment | Author=[Louis Isaac Rabinowitz | Page=447

- ^ Maimonides (1974). Sefer Mishneh Torah - HaYad Ha-Chazakah (Maimonides' Code of Jewish Law) (in Hebrew). Vol. 7. Jerusalem: Pe'er HaTorah. p. 31 [16a] (Hil. Sanhedrin 12:2). OCLC 122758200.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Sanhedrin, page 17a. Also Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Sanhedrin, Chapter 9.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin 81b)

- ^ "מגילת תענית". www.data.ac.il.

- ^ Mishnah Sanhedrin 7:1

- ^ Sanhedrin 6:4, 75b

- ^ a b Marcus Jastrow, S. Mendelsohn (1906). "Capital punishment". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Mishneh Torah Hilchot Sanhedrin 15:10

- ^ a b c Marcus Jastrow, S. Mendelsohn, Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. Capital Punishment

- ^ "Sanhedrin 45 ~ Stoning and the Height of a Lethal Fall". Talmudology. 2017-08-30. Retrieved 2024-09-09.

- ^ Bar, Shaul (2012). "The Punishment of Burning in the Hebrew Bible" (PDF). The University of Memphis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-12-22.

- ^ "The Death Penalty in Jewish Tradition." My Jewish Learning. 20 January 2018

- ^ Biale, Rachel. "The Death Penalty in Jewish Teachings." Bend the Arc. 4 October 2012. 2 November 2017.

- ^ "Opinion Polls: Death Penalty Support and Religion". Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved 2021-07-19.

- ^ Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. Handbook of Jewish Thought, Volume II, pp. 170-71

- ^ Responsa Iggerot Moshe, Choshen Mishpat 2:68

- ^ Shalom Carmy, Progress and Punishment

- ^ Bokser, Ben Zion. "Statement on capital punishment, 1960." Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards 1927-1970, Volume III, pp. 1537-1538.

- ^ "Position of the Reform Movement on the Death Penalty". Religious Action Center. Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ https://shj.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Volume-XLV-2016-Number-2-Change-Fear-and-Hope-in-the-Twenty-First-Century.pdf [bare URL PDF]

Further reading

[edit]- Capital Punishment, Jewish Virtual Library

- The Death Penalty in Jewish Tradition

- Jewish Law Legal Briefs

- Berkowitz, Beth A. (2002). "Decapitation and the discourse of antisyncretism in the Babylonian Talmud". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 70 (2): 743–770. doi:10.1093/jaar/70.4.743.