Bootleg recording

A bootleg recording is an audio or video recording of a performance not officially released by the artist or under other legal authority. Making and distributing such recordings is known as bootlegging. Recordings may be copied and traded among fans without financial exchange, but some bootleggers have sold recordings for profit, sometimes by adding professional-quality sound engineering and packaging to the raw material. Bootlegs usually consist of unreleased studio recordings, live performances or interviews without the quality control of official releases.

Bootlegs reached new popularity with Bob Dylan's Great White Wonder, a compilation of studio outtakes and demos released in 1969 using low-priority pressing plants. The following year, the Rolling Stones' Live'r Than You'll Ever Be, an audience recording of a late 1969 show, received a positive review in Rolling Stone. Subsequent bootlegs became more sophisticated in packaging, particularly the Trademark of Quality label with William Stout's cover artwork. Compact disc bootlegs first appeared in the 1980s, and Internet distribution became increasingly popular in the 1990s.

Changing technologies have affected the recording, distribution, and profitability of the bootlegging industry. The copyrights for the music and the right to authorise recordings often reside with the artist, according to several international copyright treaties. The recording, trading and sale of bootlegs continues to thrive, even as artists and record companies release official alternatives.

Definitions

[edit]The word bootleg originates from the practice of smuggling illicit items in the legs of tall boots, particularly the smuggling of alcohol during the American Prohibition era. The word, over time, has come to refer to any illegal or illicit product. This term has become an umbrella term for illicit, unofficial, or unlicensed recordings, including vinyl LPs, silver CDs, or any other commercially sold media or material.[1] The alternate term ROIO (an acronym meaning "Recording of Indeterminate/Independent Origin") or VOIO (Video...) arose among Pink Floyd collectors, to clarify that the recording source and copyright status were hard to determine.[2]

Although unofficial and unlicensed recordings had existed before the 1960s, the very first rock bootlegs came in plain sleeves with the titles rubber stamped on them.[3] However, they quickly developed into more sophisticated packaging, in order to distinguish the manufacturer from inferior competitors.[4] With today's packaging and desktop publishing technology, even the layman can create "official" looking CDs. With the advent of the cassette and CD-R, however, some bootlegs are traded privately with no attempt to be manufactured professionally. This is even more evident with the ability to share bootlegs via the Internet.[5]

Bootlegs should not be confused with counterfeit or unlicensed recordings, which are merely unauthorised duplicates of officially released recordings, often attempting to resemble the official product as closely as possible. Some record companies have considered that any record issued outside of their control, and for which they do not receive payment, to be a counterfeit, which includes bootlegs. However, some bootleggers are keen to stress that the markets for bootleg and counterfeit recordings are different, and a typical consumer for a bootleg will have bought most or all of that artist's official releases anyway.[6]

The most common type is the live bootleg, often an audience recording, which is created with sound recording equipment smuggled into a live concert. Many artists and live venues prohibit this form of recording, but from the 1970s onwards the increased availability of portable technology made such bootlegging easier, and the general quality of these recordings has improved over time as consumer equipment becomes sophisticated. A number of bootlegs originated with FM radio broadcasts of live or previously recorded live performances.[7] Other bootlegs may be soundboard recordings taken directly from a multi-track mixing console used to feed the public address system at a live performance. Artists may record their own shows for private review, but engineers may surreptitiously take a copy of this,[a] which ends up being shared. As a soundboard recording is intended to supplement the natural acoustics of a gig, a bootleg may have an inappropriate mix of instruments, unless the gig is so large that everything needs to be amplified and sent to the desk.[9]

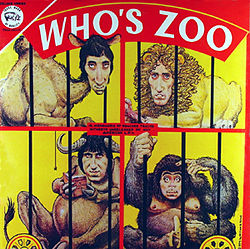

Some bootlegs consist of private or professional studio recordings distributed without the artist's involvement, including demos, works-in-progress or discarded material. These might be made from private recordings not meant to be widely shared, or from master recordings stolen or copied from an artist's home, a recording studio or the offices of a record label, or they may be copied from promotional material issued to music publishers or radio stations, but not for commercial release.[10] A theme of early rock bootlegs was to copy deleted records, such as old singles and B-sides, onto a single LP, as a cheaper alternative to obtaining all the original recordings. Strictly speaking, these were unlicensed recordings, but, because the work required to clear all the copyrights and publishing of every track for an official release was considered to be prohibitively expensive, the bootlegs became popular. Some bootlegs, however, did lead to official releases. The Who's Zoo bootleg, collecting early singles by the Who, inspired the official album Odds And Sods, which beat the bootleggers by issuing unreleased material, while various compilations of mid-1960s bands inspired the Nuggets series of albums.[11]

History

[edit]Pre-1960s

[edit]According to the enthusiast and author Clinton Heylin, the concept of a bootleg record can be traced back to the days of William Shakespeare, when unofficial transcripts of his plays would be published.[12] At that time, society was not particularly interested in who had authored a work. The "cult of authorship" was established in the 19th century, resulting in the first Berne Convention in 1886 to cover copyright. The US did not agree to the original terms, resulting in many "piratical reprints" of sheet music being published there by the end of the century.[13]

Film soundtracks were often bootlegged. If the officially released soundtrack had been re-recorded with a house orchestra, there would be demand for the original audio recording taken directly from the film. One example was a bootleg of Judy Garland performing Annie Get Your Gun (1950), before Betty Hutton replaced her early in production, but after a full soundtrack had been recorded.[14] The Recording Industry Association of America objected to unauthorised releases and attempted several raids on production.[15] The Wagern-Nichols Home Recordist Guild recorded numerous performances at the Metropolitan Opera House, and openly sold them without paying royalties to the writers and performers. The company was sued by the American Broadcasting Company and Columbia Records (whom at the time held the official rights to recordings made at the opera house), who obtained a court injunction against producing the record.[16]

Saxophone player and Charlie Parker fan Dean Benedetti famously bootlegged several hours of solos by Parker at live clubs in 1947 and 1948 via tape and disc recordings. Benedetti stored the recordings and they were only rediscovered in 1988, over thirty years after Benedetti had died, by which time they had become a "jazz myth." Most of these recordings were later released officially on Mosaic Records in the 1990s.[17]

1960s

[edit]

The first popular rock music bootleg resulted from Bob Dylan's activities between largely disappearing from the public eye after his motorcycle accident in 1966, and the release of John Wesley Harding at the end of 1967. After a number of artists had hits with Dylan songs that he had not officially released himself, demand increased for Dylan's original recordings, particularly when they started airing on local radio in Los Angeles. Through various contacts in the radio industry, a number of pioneering bootleggers managed to buy a reel-to-reel tape containing a selection of unreleased Dylan songs intended for distribution to music publishers and wondered if it would be possible to manufacture them on an LP. They managed to convince a local pressing plant to press between 1,000 and 2,000 copies discreetly, paying in cash and avoiding using real names or addresses. Since the bootleggers could not commercially print a sleeve, due to it attracting too much attention from recording companies, the LP was issued in a plain white cover with Great White Wonder rubber stamped on it.[3] Subsequently, Dylan became one of the most popular artists to be bootlegged with numerous releases.[18]

When the Rolling Stones announced their 1969 American tour, their first in the U.S. for several years, an enterprising bootlegger known as "Dub" decided to record some of the shows. He purchased a Sennheiser 805 "shotgun" microphone and a Uher 4000 reel to reel tape recorder specifically for recording the performances, smuggling them into the venues.[19] The resulting bootleg, Live'r Than You'll Ever Be, was released shortly before Christmas 1969, mere weeks after the tour had finished, and in January 1970 received a rave review in Rolling Stone, who described the sound quality as "superb, full of presence, picking up drums, bass, both guitars and the vocals beautifully ... it is the ultimate Rolling Stones album".[20] The bootleg sold several tens of thousands of copies, orders of magnitude more than a typical classical or opera bootleg,[21] and its success resulted in the official release of the live album Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out! later in the year. "Dub" was one of the founders of the Trade Mark of Quality (TMOQ or TMQ) bootleg record label.[22]

1970s

[edit]During the 1970s the bootleg industry in the United States expanded rapidly, coinciding with the era of stadium rock or arena rock. Vast numbers of recordings were issued for profit by bootleg labels such as Kornyfone and TMQ.[23] The large followings of rock artists created a lucrative market for the mass production of unofficial recordings on vinyl, as it became evident that more and more fans were willing to purchase them.[24] In addition, the huge crowds which turned up to these concerts made the effective policing of the audience for the presence of covert recording equipment difficult. Led Zeppelin quickly became a popular target for bootleggers on the strength and frequency of their live concerts; Live on Blueberry Hill, recorded at the LA Forum in 1970, was sufficiently successful to incur the wrath of manager Peter Grant.[25] Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band recorded numerous concerts for radio broadcast in the 1970s, which resulted in many Springsteen bootlegs.[26]

Some bootleggers noticed rock fans that had grown up with the music in the 1960s wanted rare or unreleased recordings of bands that had split up and looked unlikely to reform. For instance, the release of Golden Eggs, a bootleg of outtakes by the Yardbirds had proven to be so popular that the bootlegger had managed to interview the band's Keith Relf for the sequel, More Golden Eggs.[27] Archive live performances became popular; a 1970 release of Dylan's set with the Hawks (later to become the Band) at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in 1966 (incorrectly assumed to be the Royal Albert Hall for years) was critically and commercially successful owing to the good sound quality and the concert's historical importance.[28]

In Los Angeles there were a number of record mastering and pressing plants that were not "first in line" to press records for the major labels, usually only getting work when the larger plants were overloaded. These pressing plants were more than happy to generate income by pressing bootlegs of dubious legality.[29] Sometimes they simply hid the bootleg work when record company executives would come around (in which case the printed label could show the artist and song names) and other times secrecy required labels with fictitious names. For example, a 1974 Pink Floyd bootleg called Brain Damage was released under the name the Screaming Abadabs, which was one of the band's early names.[30] Because of their ability to get records and covers pressed unquestioned by these pressing plants, bootleggers were able to produce artwork and packaging that a commercial label would be unlikely to issue – perhaps most notoriously the 1962 recording of the Beatles at the Star-Club in Hamburg, which was bootlegged as The Beatles vs. the Third Reich (a parody of the early US album The Beatles vs. the Four Seasons), or Elvis' Greatest Shit, a collection of the least successful of Elvis Presley's recordings, mostly from film soundtracks.[31]

Bootleg collectors in this era generally relied on Hot Wacks, an annual underground magazine listing known bootlegs and information about recent releases. It provided the true information on bootlegs with fictitious labels, and included details on artists and track listings, as well as the source and sound quality of the various recordings.[32][33]

Initially, knowledge of bootlegs and where to purchase them spread by word of mouth.[34] The pioneering bootlegger Rubber Dubber sent copies of his bootleg recordings of live performances to magazines such as Rolling Stone in an attempt to get them reviewed. When Dylan's record company, Columbia Records objected, Rubber Dubber counteracted he was simply putting fans in touch with the music without the intermediary of a record company.[35] Throughout the 1970s most bootleg records were of poor quality, with many of the album covers consisting of nothing more than cheap photocopies. The packaging became more sophisticated towards the end of the decade and continued into the 1980s.[36] Punk rock saw a brief entry into the bootleg market in the 1970s, particularly the bootleg Spunk, a series of outtakes by the Sex Pistols. It received a good review from Sounds' Chas de Whalley, who said it was an album "no self-respecting rock fan would turn his nose up" at.[37]

1980s

[edit]

The 1980s saw the increased use of audio cassettes and videotapes for the dissemination of bootleg recordings, as the affordability of private dubbing equipment made the production of multiple copies significantly easier.[38] Cassettes were also smaller, easier to ship, and could be sold or traded more affordably than vinyl. Cassette culture and tape trading, propelled by the DIY ethic of the punk subculture, relied on an honor system where people who received tapes from fellow traders made multiple copies to pass on to others within the community.[39] For a while, stalls at major music gatherings such as the Glastonbury Festival sold mass copies of bootleg soundboard recordings of bands who, in many cases, had played only a matter of hours beforehand. However, officials soon began to counteract this illegal activity by making raids on the stalls and, by the end of the 1980s, the number of festival bootlegs had consequently dwindled.[40][36]

One of the most critically acclaimed bootlegs from the 1980s is The Black Album by Prince. The album was to have been a conventional major-label release in late 1987, but on 1 December, immediately before release, Prince decided to pull the album, requiring 500,000 copies to be destroyed.[41] A few advance copies had already shipped, which were used to create bootlegs. This eventually led to the album's official release.[42] Towards the end of the 1980s, the Ultra Rare Trax series of bootlegs, featuring studio outtakes of the Beatles, showed that digital remastering onto compact disc could produce a high-quality product that was comparable with official studio releases.[43]

1990s–present

[edit]Following the success of Ultra Rare Trax, the 1990s saw an increased production of bootleg CDs, including reissues of shows that had been recorded decades previously. In particular, companies in Germany and Italy exploited the more relaxed copyright laws in those countries by pressing large numbers of CDs and including catalogs of other titles on the inlays, making it easier for fans to find and order shows direct.[36][44] Similarly, relaxed copyright laws in Australia meant that the most serious legal challenge to unauthorised releases were made on the grounds of trademark law by Sony Music Entertainment in 1993. Court findings were in favour of allowing the release of unauthorised recordings clearly marked as "unauthorised". The updated GATT 1994 agreement soon closed this so-called "protection gap" in all three aforementioned countries effective 1 January 1995.[45]

By this time, access to the Internet was increasing, and bootleg review sites began to appear. The quality control of bootlegs began to be scrutinised, as a negative review of one could adversely harm sales.[46] Bootlegs began to increase in size, with multi-CD packages being common. In 1999, a 4-CD set was released containing three and a half hours of recording sessions for the Beach Boys' "Good Vibrations", spanning seven months.[47]

The tightening of laws and increased enforcement by police on behalf of the British Phonographic Industry (BPI), Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and other industry groups—often for peripheral issues such as tax evasion—gradually drove the distributors of for-profit vinyl and CD bootlegs further underground.[36] Physical bootlegging largely shifted to countries with laxer copyright laws, with the results distributed through existing underground channels, open-market sites such as eBay, and other specialised websites. By the end of the decade, eBay had forbidden bootlegs.[48]

The late 1990s saw an increase in the free trading of digital bootlegs, sharply decreasing the demand for and profitability of physical bootlegs. The rise of audio file formats such as MP3 and Real Audio, combined with the ability to share files between computers via the internet, made it simpler for collectors to exchange bootlegs. The arrival of Napster in 1999 made it easy to share bootlegs over a large computer network.[49] Older analog recordings were converted to digital format, tracks from bootleg CDs were ripped to computer hard disks, and new material was created with digital recording of various types; all of these types could now be easily shared. Instead of album-length collections or live recordings of entire shows, fans often now had the option of searching for and downloading bootlegs of songs.[50] Artists had a mixed reaction to online bootleg sharing; Bob Dylan allowed fans to download archive recordings from his official website, while King Crimson's Robert Fripp and Metallica were strongly critical of the ease with which Napster circumvented traditional channels of royalty payments.[51]

The video sharing website YouTube became a major carrier of bootleg recordings. YouTube's owner, Google, believes that under the "safe-harbor" provision of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), it cannot be held responsible for content, allowing bootleg media to be hosted on it without fear of a lawsuit. As the technology to host videos is open and available, shutting down YouTube may simply mean the content migrates elsewhere.[52] An audience recording of one of David Bowie's last concerts before he retired from touring in 2004 was uploaded to YouTube and received a positive review in Rolling Stone.[53] Bilal's unreleased second album, Love for Sale, leaked in 2006 and became one of the most infamously bootlegged recordings during the digital piracy era,[54] with its songs since remaining on YouTube.[55] Lana Del Rey's 2006 demo album Sirens leaked on YouTube in 2012.[56] In 2010, YouTube removed a 15-minute limit on videos, allowing entire concerts to be uploaded.[57]

Copyright

[edit]The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works has protected the copyrights on literary, scientific, and artistic works since 1886. Article 9 of the Convention states that: Authors of literary and artistic works protected by this Convention shall have the exclusive right of authorising the reproduction of these works, in any manner or form. ... Any sound or visual recording shall be considered as a reproduction for the purposes of this Convention.[58] This means a composer has performing rights and control over how derivative works should be used, and the rights are retained at least 50 years after death, or even longer. Even if a song is a traditional arrangement in the public domain, performing rights can still be violated.[59] Where they exist, performers rights may have a shorter duration than full copyright; for example, the Rome Convention sets a minimum term of twenty years after the performance. This created a market for bootleg CDs in the late 1980s, containing 1960s recordings.[60]

In the US, bootlegs had been a grey area in legality, but the 1976 Copyright Act extended copyright protection to all recordings, including "all misappropriated recordings, both counterfeit and pirate". This meant bootleggers would take a much greater risk, and several were arrested.[61] Bootlegs have been prohibited by federal law (17 USC 1101) since the introduction of the Uruguay Round Agreements Act (URAA, PL 103-465) in 1994, as well as by state law. The federal bootleg statute does not pre-empt state laws, which also apply both prior to and since the passage of the federal bootleg statute. The US v. Martignon case challenged the constitutionality of the federal bootleg statute, and in 2004, U.S. District Judge Harold Baer Jr. struck down the part banning the sale of bootleg recordings of live music, ruling that the law unfairly grants a seemingly perpetual copyright period to the original performances.[62][63] In 2007, Judge Baer's ruling was overruled, and the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit found that the anti-bootlegging statute was within the power of Congress.[64]

Official releases

[edit]

Record companies have described bootlegs as "grey area, live recordings", describing them as "semi-condoned".[65] Research into bootleg consumers found that they are committed fans of the artist; a study of Bruce Springsteen fans showed 80% felt some bootlegs were essential purchases despite owning every official release.[65] Springsteen has said he understands why fans buy bootlegs, but dislikes the market due to the lack of quality control and making profit over pleasing fans.[66] Frank Zappa hated bootlegs and wished to control his recordings, so he created the Beat the Boots! boxed sets, each containing LPs that were direct copies of existing bootlegs. He set up a hotline for fans to report bootlegs and was frustrated that the FBI were not interested in prosecuting. The first set included As An Am Zappa, in which he can be heard complaining about bootleggers releasing new material before he could.[67]

Throughout their career, the Grateful Dead were known to tolerate taping of the live shows. There was a demand from fans to hear the improvisations that resulted from each show, and taping appealed to the band's general community ethos.[68] They were unique among bands in that their live shows tended not to be pressed and packaged as LPs, but remained in tape form to be shared between tapers.[69] The group were strongly opposed to commercial bootlegging and policed stores that sold them, while the saturation of tapes among fans suppressed any demand for product.[70] In 1985, the Grateful Dead, after years of tolerance, officially endorsed live taping of their shows, and set up dedicated areas that they believed gave the best sound recording quality.[71] Other bands, including Pearl Jam, Phish and the Dave Matthews Band tolerate taping in a similar manner to the Grateful Dead, provided no profit is involved. Because of the questionable legality of bootlegs, fans have sometimes simply dubbed a bootleg onto tape and freely passed it onto others.[33]

Many recordings first distributed as bootleg albums were later released officially by the copyright holder. Provided the official release matches the quality of the bootleg, demand for the latter can be suppressed. One of the first rock bootlegs, containing John Lennon's performance with the Plastic Ono Band at the 1969 Toronto Rock and Roll Revival, was released officially as Live Peace in Toronto 1969 by the end of the year, effectively ending sales of the bootleg.[72] The release of Bob Dylan's 1966 Royal Albert Hall concert on Vol. 4 of his Bootleg Series in 1998 included both the acoustic and electric sets, more than any bootleg had done.[73]

In 2002, Dave Matthews Band released Busted Stuff in response to the Internet-fuelled success of The Lillywhite Sessions, which they had not intended to release. Queen released 100 bootlegs for sale as downloads on their website, with profits going to the Mercury Phoenix Trust.[74] Although the recording of concerts by King Crimson and its guitarist Robert Fripp is prohibited, Fripp's music company Discipline Global Mobile (DGM) sells concert recordings as downloads, especially "archival" recordings from the concerts' mixing consoles. With an even greater investment of sound engineering, DGM has released "official bootlegs", which are produced from one or more fan bootlegs.[75] DGM's reverse engineering of the distribution-networks for bootlegs helped it to make a successful transition to an age of digital distribution, "unique" (in 2009) among music labels.[76] In the 21st century, artists responded to the demand for recordings of live shows by experimenting with the sale of authorized bootlegs made directly from the soundboard, with a superior quality to an audience recording.[77] Metallica, Phish and Pearl Jam have regularly distributed instant live bootlegs of their concerts. In 2014, Bruce Springsteen announced he would allow fans to purchase a USB stick at concerts, which could be used to download a bootleg of the show.[78]

According to a 2012 report in Rolling Stone, many artists have now concluded that the volume of bootlegged performances on YouTube in particular is so large that it is counterproductive to enforce it, and they should use it as a marketing tool instead. Music lawyer Josh Grier said that most artists had "kind of conceded to it".[57] Justin Bieber has embraced the distribution of video clips via Twitter to increase his fanbase.[57]

Australian psychedelic rock band King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard have a unique approach to bootlegging. An entire section of their official website is devoted to releasing bootlegs of their shows. The band permits the distribution and sale of bootlegs, so long as they are given hard copies on vinyl and CD.[79]

See also

[edit]- Cam, a bootleg recording of a film in a movie theatre

- Magnitizdat, for live recordings of banned bards and musicians in the Soviet Union

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ A bootleg of Bruce Springsteen was distributed after the band's sound engineer left a cassette in his car while it was being repaired. A bootlegger copied the cassette during the work, then returned it without arousing suspicion.[8]

Citations

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 6.

- ^ Greenman, Ben (1995). Netmusic: your complete guide to rock and more on the Internet and online services. Random House. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-679-76385-7.

- ^ a b Heylin 1994, p. 45.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 92.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 483.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 7.

- ^ Collectible '70s: A Price Guide to the Polyester Decade. Krause Publications. 2011. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4402-2748-6.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 278.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 256.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 44.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 196.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 37.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 31.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 32.

- ^ Watrous, Peter (23 December 1990). "POP VIEW; The Legendary, Lost Recordings Of Charlie Parker". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 394.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 60.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 61.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 65.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 66.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 102.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 117.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 98.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 73–74, 76.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 63.

- ^ Slugbelch. "A Brief History Of Bootlegs". The Pink Floyd Vinyl Bootleg Guide. Backtrax Records. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 188.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 130–131.

- ^ a b Shuker 2013, p. 105.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 174.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 103.

- ^ a b c d Galloway, Simon (1999). "Bootlegs, an insight into the shady side of music collecting". More Music e-zine. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 170.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 79.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 123–4.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 428.

- ^ Gulla, Bob (2008). Icons of R&B and Soul: Smokey Robinson and the Miracles ; The Temptations ; The Supremes ; Stevie Wonder. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-313-34046-8.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 163.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 282–3.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 369.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 279.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 458.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 462.

- ^ "half.com, buy.com Team on Latest Used Goods Sites". Billboard. 18 November 2000. p. 115. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 476.

- ^ Jordan, Keith. "T'Internet – A Bootleg Fan's Paradise Archived 16 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine" – The Past, Present and Future of Bootlegs considering the internet. NPF Magazine. November 2006.

- ^ Heylin 2010, pp. 478–9.

- ^ Hilderbrand 2009, p. 242.

- ^ Greene, Andy (4 December 2015). "Bootleg of the Week: David Bowie Live in Atlantic City 5/29/04". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Larrier, Travis (4 March 2013). "Bilal Is the Future (And the Present ... And the Past)". The Shadow League. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Hull, Tom (31 August 2020). "Music Week". Tom Hull – on the Web. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Lana Del Rey's first album 'Sirens' leaks – The Strut". Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Knopper, Steve (17 December 2012). "Top Artists Adjust to New World of YouTube Bootlegs". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ "Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Article 9". World Intellectual Property Organisation. September 1886. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- ^ "Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works". Cornell University Law School. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ Heylin 2010, p. 289.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 125.

- ^ Landau, Michael (April 2005). "Constitutional Impediments to Protecting the Live Musical Performance Right in the United States". IPRinfo Magazine. IPR University Center. Retrieved 16 October 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ McClam, Erin (September 2004). "N.Y. judge strikes down anti-bootleg law". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- ^ US v. Martignon, 492 F. 3d 140 (2d Cir. 2007).

- ^ a b Shuker 2013, p. 106.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 136.

- ^ Heylin 1994, pp. 195, 395.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 156.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 157.

- ^ Heylin 1994, p. 397.

- ^ Cummings 2013, p. 158.

- ^ Heylin 1994.

- ^ "The Bootleg Series, Vol. 4". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Queen take on the Bootleggers with downloads of their own". EConsultancy. 11 November 2004. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ Bambarger (1998, p. 86): Bambarger, Bradley (11 July 1998). "Fripp label does it his way: Guitarist follows own muse in business, too". Billboard. Vol. 110, no. 28. pp. 13 and 86.

- ^ Anonymous, Belfast Telegraph (18 August 2009). "Jam and the joys of music distribution in today's world". Belfast Telegraph. Independent News and Media PLC. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ "The Encore Series". themusic.com. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Greene, Andy (17 January 2014). "Bruce Springsteen Formalizes Plans for Instant Live Bootlegs". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ "Bootlegger". King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

Bibliography

- Cummings, Alex Sayf (2013). Democracy of Sound: Music Piracy and the Remaking of American Copyright in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-932372-2.

- Heylin, Clinton (1994). The Great White Wonders – A History of Rock Bootlegs. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-85777-7.

- Heylin, Clinton (2010). Bootleg! The Rise And Fall Of The Secret Recording Industry. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-217-9.

- Hilderbrand, Lucas (2009). Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9219-4.

- Shuker, Roy (2013). Wax Trash and Vinyl Treasures: Record Collecting as a Social Practice. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-9397-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Thompson, Dave. A Music Lover's Guide to Record Collecting. Backbeat Books, September 2002. (ISBN 0-87930-713-7)

- Trew, Stuart. "The Double Life of a Bootlegger", Warrior Magazine, Sept. 2004, p. 6–8. N.B.: Discusses bootlegging in the Canadian context.