Emoticon

An emoticon (/əˈmoʊtəkɒn/, ə-MOH-tə-kon, rarely /ɪˈmɒtɪkɒn/, ih-MOTT-ih-kon),[1][2][3][4] short for emotion icon,[5] is a pictorial representation of a facial expression using characters—usually punctuation marks, numbers and letters—to express a person's feelings, mood or reaction, without needing to describe it in detail.

The first ASCII emoticons are generally credited to computer scientist Scott Fahlman, who proposed what came to be known as "smileys"—:-) and :-(—in a message on the bulletin board system (BBS) of Carnegie Mellon University in 1982. In Western countries, emoticons are usually written at a right angle to the direction of the text. Users from Japan popularized a kind of emoticon called kaomoji, using Japanese's larger character sets. This style arose on ASCII NET of Japan in 1986.[6][7] They are also known as verticons (from vertical icon) due to their readability without rotations.[8]

As SMS mobile text messaging and the Internet became widespread in the late 1990s, emoticons became increasingly popular and were commonly used in texting, Internet forums and emails. Emoticons have played a significant role in communication through technology, and some devices and applications have provided stylized pictures that do not use text punctuation. They offer another range of "tone" through texting through facial gestures.[9] Emoticons were the precursors to modern emojis.

History

[edit]Different uses of text characters (pre-1981)

[edit]

In 1648, poet Robert Herrick wrote, "Tumble me down, and I will sit Upon my ruins, (smiling yet:)." Herrick's work predated any other recorded use of brackets as a smiling face by around 200 years. However, experts doubted the inclusion of the colon in the poem was deliberate and if it was meant to represent a smiling face. English professor Alan Jacobs argued that "punctuation, in general, was unsettled in the seventeenth century ... Herrick was unlikely to have consistent punctuational practices himself, and even if he did he couldn't expect either his printers or his readers to share them."[10] 17th century typography practice often placed colons and semicolons within parentheses, including 14 instances of ":)" in Richard Baxter's 1653 Plain Scripture Proof of Infants Church-membership and Baptism.[11]

Precursors to modern emoticons have existed since the 19th century.[12][13][14] The National Telegraphic Review and Operators Guide in April 1857 documented the use of the number 73 in Morse code to express "love and kisses"[15] (later reduced to the more formal "best regards"). Dodge's Manual in 1908 documented the reintroduction of "love and kisses" as the number 88. New Zealand academics Joan Gajadhar and John Green comment that both Morse code abbreviations are more succinct than modern abbreviations such as LOL.[16]

The transcript of one of Abraham Lincoln's speeches in 1862 recorded the audience's reaction as: "(applause and laughter ;)".[12][17] There has been some debate whether the glyph in Lincoln's speech was a typo, a legitimate punctuation construct or the first emoticon.[18] Linguist Philip Seargeant argues that it was a simple typesetting error.[19]

Before March 1881, the examples of "typographical art" appeared in at least three newspaper articles, including Kurjer warszawski (published in Warsaw) from March 5, 1881, using punctuation to represent the emotions of joy, melancholy, indifference and astonishment.[20]

In a 1912 essay titled "For Brevity and Clarity", American author Ambrose Bierce suggested facetiously[12][17] that a bracket could be used to represent a smiling face, proposing "an improvement in punctuation" with which writers could convey cachinnation, loud or immoderate laughter: "it is written thus ‿ and presents a smiling mouth. It is to be appended, with the full stop, to every jocular or ironical sentence".[12][22] In a 1936 Harvard Lampoon article, writer Alan Gregg proposed combining brackets with various other punctuation marks to represent various moods. Brackets were used for the sides of the mouth or cheeks, with other punctuation used between the brackets to display various emotions: (-) for a smile, (--) (showing more "teeth") for laughter, (#) for a frown and (*) for a wink.[12][23] An instance of text characters representing a sideways smiling and frowning face could be found in the New York Herald Tribune on March 10, 1953, promoting the film Lili starring Leslie Caron.[24]

The September 1962 issue of MAD magazine included an article titled "Typewri-toons". The piece, featuring typewriter-generated artwork credited to "Royal Portable", was entirely made up of repurposed typography, including a capital letter P having a bigger 'bust' than a capital I, a lowercase b and d discussing their pregnancies, an asterisk on top of a letter to indicate the letter had just come inside from snowfall, and a classroom of lowercase n's interrupted by a lowercase h "raising its hand".[25] A further example attributed to a Baltimore Sunday Sun columnist appeared in a 1967 article in Reader's Digest, using a dash and right bracket to represent a tongue in one's cheek: —).[12][17][26] Prefiguring the modern "smiley" emoticon,[12][19] writer Vladimir Nabokov told an interviewer from The New York Times in 1969, "I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile—some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket, which I would now like to trace in reply to your question."[27]

In the 1970s, the PLATO IV computer system was launched. It was one of the first computers used throughout educational and professional institutions, but rarely used in a residential setting.[28] On the computer system, a student at the University of Illinois developed pictograms that resembled different smiling faces. Mary Kalantzis and Bill Cope stated this likely took place in 1972, and they claimed these to be the first emoticons.[29][30]

ASCII emoticons use in digital communication (1982–mid-1990s)

[edit]Carnegie Mellon computer scientist Scott Fahlman is generally credited with the invention of the digital text-based emoticon in 1982.[19][31][13] The use of ASCII symbols, a standard set of codes representing typographical marks, was essential to allow the symbols to be displayed on any computer.[32] In Carnegie Mellon's bulletin board system, Fahlman proposed colon–hyphen–right bracket :-) as a label for "attempted humor" to try to solve the difficulty of conveying humor or sarcasm in plain text.[33][13] Fahlman sent the following message[a] after an incident where a humorous warning about a mercury spill in an elevator was misunderstood as serious:[17][19][35]

19-Sep-82 11:44 Scott E Fahlman :-)

From: Scott E Fahlman <Fahlman at Cmu-20c>

I propose that the following character sequence for joke markers:

:-)

Read it sideways. Actually, it is probably more economical to mark

things that are NOT jokes, given current trends. For this, use

:-(

Within a few months, the smiley had spread to the ARPANET[36][non-primary source needed] and Usenet.[37][non-primary source needed] Other suggestions on the forum included an asterisk * and an ampersand &, the latter meant to represent a person doubled over in laughter,[38][35] as well as a percent sign % and a pound sign #.[39] Scott Fahlman suggested that not only could his emoticon communicate emotion, but also replace language.[33] Since the 1990s, emoticons (colon, hyphen and bracket) have become integral to digital communications,[14] and have inspired a variety of other emoticons,[13][40] including the "winking" face using a semicolon ;-),[41] XD, a representation of the Face with Tears of Joy emoji and the acronym LOL.[42]

In 1996, The Smiley Company was established by Nicolas Loufrani and his father Franklin as a way of commercializing the smiley trademark. As part of this, The Smiley Dictionary website focused on ASCII emoticons, where a catalogue was made of them. Many other people did similar to Loufrani from 1995 onwards, including David Sanderson creating the book Smileys in 1997. James Marshall also hosted an online collection of ASCII emoticons that he completed in 2008.[42]

A researcher at Stanford University surveyed the emoticons used in four million Twitter messages and found that the smiling emoticon without a hyphen "nose" :) was much more common than the original version with the hyphen :-). Linguist Vyvyan Evans argues that this represents a shift in usage by younger users as a form of covert prestige: rejecting a standard usage in order to demonstrate in-group membership.[43]

Graphical emoticons and other developments (1990s–present)

[edit]Loufrani began to use the basic text designs and turned them into graphical representations. They are now known as graphical emoticons. His designs were registered at the United States Copyright Office in 1997 and appeared online as GIF files in 1998.[44][45][46] For ASCII emoticons that did not exist to convert into graphical form, Loufrani also backward engineered new ASCII emoticons from the graphical versions he created. These were the first graphical representations of ASCII emoticons.[47] He published his Smiley icons as well as emoticons created by others, along with their ASCII versions, in an online Smiley Dictionary in 2001.[44] This dictionary included 640 different smiley icons[48][49] and was published as a book called Dico Smileys in 2002.[44][50] In 2017, British magazine The Drum referred to Loufrani as the "godfather of the emoji" for his work in the field.[51]

On September 23, 2021, it was announced that Scott Fahlman was holding an auction for the original emoticons he created in 1982. The auction was held in Dallas, United States, and sold the two designs as non-fungible tokens (NFT).[52] The online auction ended later that month, with the originals selling for US$237,500.[53]

In some programming languages, certain operators are known informally by their emoticon-like appearance. This includes the Spaceship operator <=> (a comparison), the Diamond operator <> (for type hinting) and the Elvis operator ?: (a shortened ternary operator).[54]

Styles

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Western

[edit]Usually, emoticons in Western style have the eyes on the left, followed by the nose and the mouth. It is commonly placed at the end of a sentence, replacing the full stop. The two-character version :), which omits the nose, is very popular. The most basic emoticons are relatively consistent in form, but some can be rotated (making them tiny ambigrams). There are also some variations to emoticons to get new definitions, like changing a character to express another feeling. For example, :( equals sad and :(( equals very sad. Weeping can be written as :'(. A blush can be expressed as :">. Others include wink ;), a grin :D, :P for tongue out, and smug :->; they can be used to denote a flirting or joking tone, or may be implying a second meaning in the sentence preceding it.[55] ;P, such as when blowing a raspberry. An often used combination is also <3 for a heart and </3 for a broken heart. :O is also sometimes used to depict shock. :/ is used to depict melancholy, disappointment or disapproval. :| may be used to depict a neutral face.

A broad grin is sometimes shown with crinkled eyes to express further amusement; XD and the addition of further "D" letters can suggest laughter or extreme amusement, e.g., XDDDD. The "3" in X3 and :3 represents an animal's mouth. An equal sign is often used for the eyes in place of the colon, seen as =). It has become more acceptable to omit the hyphen, whether a colon or an equal sign is used for the eyes.[56] One linguistic study has indicated that the use of a nose in an emoticon may be related to the user's age, with younger people less likely to use a nose.[57]

Some variants are also more common in certain countries due to keyboard layouts. For example, the smiley =) may occur in Scandinavia. Diacritical marks are sometimes used. The letters Ö and Ü can be seen as emoticons, as the upright versions of :O (meaning that one is surprised) and :D (meaning that one is very happy), respectively. In countries where the Cyrillic alphabet is used, the right parenthesis ) is used as a smiley. Multiple parentheses )))) are used to express greater happiness, amusement or laughter. The colon is omitted due to being in a lesser-known position on the ЙЦУКЕН keyboard layout. The 'shrug' emoticon, ¯\_(ツ)_/¯, uses the glyph ツ from the Japanese katakana writing system.

Kaomoji (Japan ASCII movement)

[edit]Kaomoji are often seen as the Japanese development of emoticons that is separate to the Scott Fahlman movement, which started in 1982. In 1986, a designer began to use brackets and other ASCII text characters to form faces. Over time, they became more often differentiated from each other, although both use ASCII characters. However, more westernised Kaomojis have dropped the brackets, such as owo, uwu and TwT, popularised in internet subcultures such as the anime and furry communities.

2channel

[edit]Users of the Japanese discussion board 2channel, in particular, have developed a variety emoticons using characters from various scripts, such as Kannada, as in ಠ_ಠ (for a look of disapproval, disbelief or confusion). Similarly, the letter ರೃ was used in emoticons to represent a monocle and ಥ to represent a tearing eye. They were picked up by 4chan and spread to other Western sites soon after. Some have become characters in their own right like Monā.

Korean

[edit]In South Korea, emoticons use Korean Hangul letters, and the Western style is rarely used.[58] The structures of Korean and Japanese emoticons are somewhat similar, but they have some differences. Korean style contains Korean jamo (letters) instead of other characters.

The consonant jamos ㅅ, ㅁ or ㅂ can be used as the mouth or nose component and ㅇ, ㅎ or ㅍ for the eyes. Using quotation marks " and apostrophes ' are also commonly used combinations. Vowel jamos such as ㅜ and ㅠ can depict a crying face. Example: ㅜㅜ, (same function as T in Western style). Sometimes ㅡ (not an em-dash "—", but a vowel jamo), a comma (,) or an underscore (_) is added, and the two character sets can be mixed together, as in ㅠ.ㅡ, ㅡ^ㅜ and ㅜㅇㅡ. Also, semicolons and carets are commonly used in Korean emoticons; semicolons can mean sweating, examples of it are -;/, --^ and -_-;;.

Chinese ideographic

[edit]The character 囧 (U+56E7), which means 'bright', may be combined with the posture emoticon Orz, such as 囧rz. The character existed in Oracle bone script but was rarely used until its use as an emoticon,[59] documented as early as January 20, 2005.[60]

Other variants of 囧 include 崮 (king 囧), 莔 (queen 囧), 商 (囧 with a hat), 囧興 (turtle) and 卣 (Bomberman). The character 槑 (U+69D1), a variant of 梅 'plum', is used to represent a double of 呆 'dull' or further magnitude of dullness. In Chinese, normally full characters (as opposed to the stylistic use of 槑) might be duplicated to express emphasis.[citation needed]

Posture emoticons

[edit]Orz

[edit]

Orz resembles a person performing a Japanese dogeza bow.Orz (other forms include: Or2, on_, OTZ, OTL, STO, JTO,[61] _no, _冂○[62] and 囧rz[60]) is an emoticon representing a kneeling or bowing person (the Japanese version of which is called dogeza), with the "o" being the head, the "r" being the arms and part of the body, and the "z" being part of the body and the legs. This stick figure can represent respect or kowtowing, but commonly appears along a range of responses, including "frustration, despair, sarcasm, or grudging respect".[63]

It was first used in late 2002 at the forum on Techside, a Japanese personal website. At the "Techside FAQ Forum" (TECHSIDE教えて君BBS(教えてBBS)), a poster asked about a cable cover, typing "_| ̄|○" to show a cable and its cover. Others commented that it looked like a kneeling person, and the symbol became popular.[64] These comments were soon deleted as they were considered off-topic. By 2005, Orz spawned a subculture: blogs have been devoted to the emoticon, and URL shortening services have been named after it. In Taiwan, Orz is associated with the concept of nice guys.[61]

o7

[edit]o7, or O7, is an emoticon that depicts a person saluting, with the o being the head and the 7 being its arm.[citation needed]

Multimedia variations

[edit]A portmanteau of emotion and sound, an emotisound is a brief sound transmitted and played back during the viewing of a message, typically an IM message or email message. The sound is intended to communicate an emotional subtext.[65] Some services, such as MuzIcons, combine emoticons and music players in an Adobe Flash-based widget.[66] In 2004, the Trillian chat application introduced a feature called "emotiblips", which allows Trillian users to stream files to their instant message recipients "as the voice and video equivalent of an emoticon".[67]

In 2007, MTV and Paramount Home Entertainment promoted the "emoticlip" as a form of viral marketing for the second season of the show The Hills. The emoticlips were twelve short snippets of dialogue from the show, uploaded to YouTube. The emoticlip concept is credited to the Bradley & Montgomery advertising firm, which wrote that they hoped it would be widely adopted as "greeting cards that just happen to be selling something".[68]

Intellectual property rights

[edit]

In 2000, Despair, Inc. obtained a U.S. trademark registration for the "frowny" emoticon :-( when used on "greeting cards, posters and art prints". In 2001, they issued a satirical press release, announcing that they would sue Internet users who typed the frowny; the company received protests when its mock release was posted on technology news website Slashdot.[70]

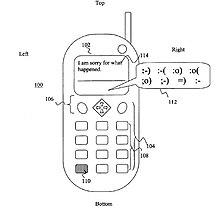

A number of patent applications have been filed on inventions that assist in communicating with emoticons. A few of these have been issued as US patents. US 6987991,[69] for example, discloses a method developed in 2001 to send emoticons over a cell phone using a drop-down menu. The stated advantage was that it eases entering emoticons.[69]

The emoticon :-) was also filed in 2006 and registered in 2008 as a European Community Trademark (CTM). In Finland, the Supreme Administrative Court ruled in 2012 that the emoticon cannot be trademarked,[71] thus repealing a 2006 administrative decision trademarking the emoticons :-), =), =(, :) and :(.[72] In 2005, a Russian court rejected a legal claim against Siemens by a man who claimed to hold a trademark on the ;-) emoticon.[73] In 2008, Russian entrepreneur Oleg Teterin claimed to have been granted the trademark on the ;-) emoticon. A license would not "cost that much—tens of thousands of dollars" for companies but would be free of charge for individuals.[73]

Unicode

[edit]A different, but related, use of the term "emoticon" is found in the Unicode Standard, referring to a subset of emoji that display facial expressions.[74] The standard explains this usage with reference to existing systems, which provided functionality for substituting certain textual emoticons with images or emoji of the expressions in question.[75]

Some smiley faces were present in Unicode since 1.1, including a white frowning face, a white smiling face and a black smiling face ("black" refers to a glyph which is filled, "white" refers to a glyph which is unfilled).[76]

| Miscellaneous Symbols (partial)[1][2][3] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+263x | ☹ | ☺ | ☻ | |||||||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

The Emoticons block was introduced in Unicode Standard version 6.0 (published in October 2010) and extended by 7.0. It covers Unicode range from U+1F600 to U+1F64F fully.[77]

| Emoticons[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1F60x | 😀 | 😁 | 😂 | 😃 | 😄 | 😅 | 😆 | 😇 | 😈 | 😉 | 😊 | 😋 | 😌 | 😍 | 😎 | 😏 |

| U+1F61x | 😐 | 😑 | 😒 | 😓 | 😔 | 😕 | 😖 | 😗 | 😘 | 😙 | 😚 | 😛 | 😜 | 😝 | 😞 | 😟 |

| U+1F62x | 😠 | 😡 | 😢 | 😣 | 😤 | 😥 | 😦 | 😧 | 😨 | 😩 | 😪 | 😫 | 😬 | 😭 | 😮 | 😯 |

| U+1F63x | 😰 | 😱 | 😲 | 😳 | 😴 | 😵 | 😶 | 😷 | 😸 | 😹 | 😺 | 😻 | 😼 | 😽 | 😾 | 😿 |

| U+1F64x | 🙀 | 🙁 | 🙂 | 🙃 | 🙄 | 🙅 | 🙆 | 🙇 | 🙈 | 🙉 | 🙊 | 🙋 | 🙌 | 🙍 | 🙎 | 🙏 |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

After that block had been filled, Unicode 8.0 (2015), 9.0 (2016) and 10.0 (2017) added additional emoticons in the range from U+1F910 to U+1F9FF. Currently, U+1F90C – U+1F90F, U+1F93F, U+1F94D – U+1F94F, U+1F96C – U+1F97F, U+1F998 – U+1F9CF (excluding U+1F9C0 which contains the 🧀 emoji) and U+1F9E7 – U+1F9FF do not contain any emoticons since Unicode 10.0.

| Supplemental Symbols and Pictographs[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1F90x | 🤀

|

🤁

|

🤂

|

🤃

|

🤄

|

🤅

|

🤆

|

🤇

|

🤈

|

🤉

|

🤊

|

🤋

|

🤌

|

🤍

|

🤎

|

🤏

|

| U+1F91x | 🤐

|

🤑

|

🤒

|

🤓

|

🤔

|

🤕

|

🤖

|

🤗

|

🤘

|

🤙

|

🤚

|

🤛

|

🤜

|

🤝

|

🤞

|

🤟

|

| U+1F92x | 🤠

|

🤡

|

🤢

|

🤣

|

🤤

|

🤥

|

🤦

|

🤧

|

🤨

|

🤩

|

🤪

|

🤫

|

🤬

|

🤭

|

🤮

|

🤯

|

| U+1F93x | 🤰

|

🤱

|

🤲

|

🤳

|

🤴

|

🤵

|

🤶

|

🤷

|

🤸

|

🤹

|

🤺

|

🤻

|

🤼

|

🤽

|

🤾

|

🤿

|

| U+1F94x | 🥀

|

🥁

|

🥂

|

🥃

|

🥄

|

🥅

|

🥆

|

🥇

|

🥈

|

🥉

|

🥊

|

🥋

|

🥌

|

🥍

|

🥎

|

🥏

|

| U+1F95x | 🥐

|

🥑

|

🥒

|

🥓

|

🥔

|

🥕

|

🥖

|

🥗

|

🥘

|

🥙

|

🥚

|

🥛

|

🥜

|

🥝

|

🥞

|

🥟

|

| U+1F96x | 🥠

|

🥡

|

🥢

|

🥣

|

🥤

|

🥥

|

🥦

|

🥧

|

🥨

|

🥩

|

🥪

|

🥫

|

🥬

|

🥭

|

🥮

|

🥯

|

| U+1F97x | 🥰

|

🥱

|

🥲

|

🥳

|

🥴

|

🥵

|

🥶

|

🥷

|

🥸

|

🥹

|

🥺

|

🥻

|

🥼

|

🥽

|

🥾

|

🥿

|

| U+1F98x | 🦀

|

🦁

|

🦂

|

🦃

|

🦄

|

🦅

|

🦆

|

🦇

|

🦈

|

🦉

|

🦊

|

🦋

|

🦌

|

🦍

|

🦎

|

🦏

|

| U+1F99x | 🦐

|

🦑

|

🦒

|

🦓

|

🦔

|

🦕

|

🦖

|

🦗

|

🦘

|

🦙

|

🦚

|

🦛

|

🦜

|

🦝

|

🦞

|

🦟

|

| U+1F9Ax | 🦠

|

🦡

|

🦢

|

🦣

|

🦤

|

🦥

|

🦦

|

🦧

|

🦨

|

🦩

|

🦪

|

🦫

|

🦬

|

🦭

|

🦮

|

🦯

|

| U+1F9Bx | 🦰

|

🦱

|

🦲

|

🦳

|

🦴

|

🦵

|

🦶

|

🦷

|

🦸

|

🦹

|

🦺

|

🦻

|

🦼

|

🦽

|

🦾

|

🦿

|

| U+1F9Cx | 🧀

|

🧁

|

🧂

|

🧃

|

🧄

|

🧅

|

🧆

|

🧇

|

🧈

|

🧉

|

🧊

|

🧋

|

🧌

|

🧍

|

🧎

|

🧏

|

| U+1F9Dx | 🧐

|

🧑

|

🧒

|

🧓

|

🧔

|

🧕

|

🧖

|

🧗

|

🧘

|

🧙

|

🧚

|

🧛

|

🧜

|

🧝

|

🧞

|

🧟

|

| U+1F9Ex | 🧠

|

🧡

|

🧢

|

🧣

|

🧤

|

🧥

|

🧦

|

🧧

|

🧨

|

🧩

|

🧪

|

🧫

|

🧬

|

🧭

|

🧮

|

🧯

|

| U+1F9Fx | 🧰

|

🧱

|

🧲

|

🧳

|

🧴

|

🧵

|

🧶

|

🧷

|

🧸

|

🧹

|

🧺

|

🧻

|

🧼

|

🧽

|

🧾

|

🧿

|

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

For historic and compatibility reasons, some other heads and figures, which mostly represent different aspects like genders, activities, and professions instead of emotions, are also found in Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs (especially U+1F466 – U+1F487) and Transport and Map Symbols. Body parts, mostly hands, are also encoded in the Dingbat and Miscellaneous Symbols blocks.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The transcript of the conversation between several computer scientists, including David Touretzky, Guy Steele and Jaime Carbonell,[34] was believed lost before it was recovered 20 years later from old backup tapes.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ "emoticon". Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "emoticon". American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "emoticon". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "emoticon - Definition of emoticon in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017.

- ^ Zimmerly, Arlene; Jaehne, Julie (2003). Computer Connections: Projects and Applications, Student Edition. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-861399-9.

Emoticon: An acronym for emotion icon, a small icon composed of punctuation characters that indicate how an e-mail message should be interpreted (that is, the writer's mood).

[page needed] - ^ "The History of Smiley Marks". Staff.aist.go.jp. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ Yasumoto-Nicolson, Ken (September 19, 2007). "The History of Smiley Marks (English)". Whatjapanthinks.com. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ N'Diaye, Karim (January 8, 2009) [2006]. "Cross-cultural investigation of Smileys". International cognition & culture institute. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ^ Williams, Alex (July 29, 2007). "(-: Just Between You and Me ;-)". The New York Times. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (April 14, 2014). "The First Emoticon May have appeared in 1648". The Atlantic.

- ^ Zimmer, Ben (April 15, 2014). "Sorry, That's Not an Emoticon in a 1648 Poem :(". Slate. Retrieved June 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Evans, Vyvyan (2017). The Emoji Code: The Linguistics Behind Smiley Faces and Scaredy Cats. New York: Picador. pp. 149–150. ISBN 978-1-250-12906-2.

- ^ a b c d e Long, Tony (September 19, 2008). "Sept. 19, 1982: Can't You Take a Joke? :-)". Wired.

Fahlman became the acknowledged originator of the ASCII-based emoticon.

- ^ a b Giannoulis, Elena; Wilde, Lukas R. A., eds. (2019). "Emoticons, Kaomoji, and Emoji: The Transformation of Communication in the Digital Age". Emoticons, Kaomoji, and Emoji: The Transformation of Communication in the Digital Age. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-95884-7.

The most commonly used emoticons, the 'smileys', have since become an integral part of digital communication.

[page needed] - ^ Hey, Tony; Pápay, Gyuri (2014). The Computing Universe: A Journey through a Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-316-12322-5.

- ^ Gajadhar, Joan; Green, John (2005). "The Importance of Nonverbal Elements in Online Chat" (PDF). EDUCAUSE Quarterly. 28 (4): 63–64. ISSN 1528-5324.

- ^ a b c d Houston, Keith (September 28, 2013). "Something to Smile About". The Wall Street Journal. p. C3. ISSN 0099-9660.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer (January 19, 2009). "Is That an Emoticon in 1862?". City Room. The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Seargeant, Philip (2019). The Emoji Revolution: How Technology is Shaping the Future of Communication. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1-108-49664-3.

The history of emoticons conventionally begins with the computer scientist Scott Fahlman who, in 1982, combined a colon, a hyphen and a round bracket as a way of indicating that a given statement was meant as a joke.

- ^ "Polona".

- ^ Telegraphische Zeichenkunst. Deutschen Postzeitung, Vol. VII. (No. 22), 1896-11-16, p. 497)

- ^ Bierce, Ambrose (1912). "For Brevity and Clarity". The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce, XI: Antepenultimata. The Neale Publishing Company. pp. 386–387.

- ^ The Harvard Lampoon, Vol. 112 No. 1, September 16, 1936, pp. 30–31. ISSN 0017-8098

- ^ New York Herald Tribune, 1953-03-10, p. 20, cols. 4–6.

- ^ MAD Magazine No. 73, September 1962, pp. 36–37. ISSN 0024-9319

- ^ Mikkelson, David (September 20, 2007). "Fact Check: Emoticon (Smiley) Origin". Snopes.

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir (1990). Strong Opinions (1st Vintage international ed.). New York: Vintage Books. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-679-72609-8. OCLC 1035656350.

- ^ Smith, Ernie (November 13, 2017). "The Greatest Computer Network You've Never Heard Of". Vice.

- ^ Kalantzis, Mary; Cope, Bill (2020). Adding Sense: Context and Interest in a Grammar of Multimodal Meaning. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-108-49534-9.

- ^ Cope, Bill; Kalantzis, Mary. "A Little History of e-Learning". Retrieved October 26, 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Doliashvili, Mariam; Ogawa, Michael-Brian C.; Crosby, Martha E. (2020). "Understanding Challenges Presented Using Emojis as a Form of Augmented Communication". In Schmorrow, Dylan D.; Fidopiastis, Cali M. (eds.). Augmented Cognition. Theoretical and Technological Approaches. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 12196. Springer Nature. p. 26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-50353-6_2. ISBN 978-3-030-50353-6. S2CID 220551348.

Scott Fahlman, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University, was credited with popularizing early text-based emoticons in 1982

- ^ Veszelszki, Ágnes (2017). Digilect: The Impact of Infocommunication Technology on Language. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 131–132. ISBN 978-3-11-049911-7.

- ^ a b Stanton, Andrea L. (2014). "Islamic Emoticons: Pious Sociability and Community Building in Online Muslim Communities.". In Benski, Tova; Fisher, Eran (eds.). Internet and Emotions. New York: Routledge. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-415-81944-2.

- ^ Fahlman, Scott. "Original Bboard Thread in which :-) was proposed". cs.cmu.edu. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ a b Garber, Megan (June 19, 2014). ") or :-)? Some Highly Scientific Data". The Atlantic.

- ^ Morris, James (October 10, 1982). "Notes – Communications Breakthrough". Newsgroup: net.works. Retrieved December 18, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Jackson, Curtis (December 3, 1982). "How to keep from being misunderstood on the net". Newsgroup: net.news. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ Hitt, Tarpley (July 17, 2020). "The Inventor of the Emoticon Tells All: 'I've Created a Virus'". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Baron, Naomi (2009). "The myth of impoverished signal: Dispelling the spoken-language fallacy for emoticons in online communication.". In Vincent, Jane; Fortunati, Leopoldina (eds.). Electronic Emotion: The Mediation of Emotion via Information and Communication Technologies. Bern: Peter Lang. p. 112. ISBN 978-3-03911-866-3.

- ^ Evans 2017, pp. 151–152.

- ^ ":-) turns 25". CNN.com. Associated Press. September 20, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007.

- ^ a b Seargeant 2019, p. 47.

- ^ Evans 2017, pp. 152–154.

- ^ a b c Mahfood, Rene (2016). "Emoji Users Are Shaping The Future Of Messaging". The Light Magazine. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017.

- ^ "Avec le smiley, 'on arrive à décontracter tout le monde'" [With the smiley, 'we get to relax everybody']. Europe 1 (in French). February 4, 2016.

- ^ Quann, Jack (July 17, 2015). "A picture paints a thousand words: Today is World Emoji Day". newstalk.com. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015.

- ^ Das, Souvik (August 4, 2016). "Emoting Out Loud: The Origin of Emojis". Digit.

- ^ Hooks, Matheus (March 10, 2022). "The Untold Story Behind the Emoji Phenomeon". Hooks magazine.

- ^ Hervez, Marc (May 9, 2016). "Qui a inventé le Smiley ? Son histoire va vous surprendre…" [Who invented the Smiley? Its history will surprise you…]. Le Parisien (in French). Archived from the original on May 10, 2019.

- ^ Danesi, Marcel (2016). The Semiotics of Emoji: The Rise of Visual Language in the Age of the Internet. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-8200-0.[page needed]

- ^ Deighton, Katie (July 24, 2017). "Creative The Smiley Company Emoji". The Drum.

- ^ "First smiley and frowny emoticons go under hammer in US". Daily Sabah. September 11, 2021.

- ^ "Erstes digitales Smiley für mehr als 200.000 Dollar als NFT versteigert" [First digital smiley sold for more than $ 200,000 as NFT]. Future Zone (in German). September 24, 2021.

- ^ Groovy Language Documentation, includes Spaceship, Elvis and Diamond operators

- ^ Dresner & Herring (2010).

- ^ "Denoser strips noses from text". SourceForge.net. February 21, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ Schnoebelen, Tyler (2012). "Do You Smile with Your Nose? Stylistic Variation in Twitter Emoticons". University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 18 (2). Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ "Korean Emoticons: The Ultimate Guide". 90 Day Korean®. March 17, 2016. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Li, Yuming; Li, Wei (April 1, 2014). The Language Situation in China. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-61451-365-0.

- ^ a b 心情很orz嗎? 網路象形文字幽默一下 [Feeling orz? Humor with Internet Hieroglyphics]. Nownews.com. January 20, 2005. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Jardin, Xeni (February 7, 2005). "All about Orz". Boing Boing. Retrieved March 24, 2009.

- ^ みんなの作った _| ̄|○クラフト "paper craft of orz" [Everyone's _| ̄|○ craft "paper craft of orz"]. Retrieved August 18, 2009.

- ^ Rodney H. Jones and Christoph A. Hafner, Understanding Digital Literacies: A Practical Introduction (London: Routledge, 2012), 126-27. ISBN 9781136212888

- ^ TECHSIDE FF11板の過去ログです [TECHSIDE FF11 board archives] (in Japanese). Archived from the original on April 30, 2003. Retrieved September 17, 2018. <正直>アフターバーナー予約してしまいました_| ̄|○←早速使ってみるw (12/23 00:20)

<ルン>/土下座_| ̄| ○のび助 ···駄目だ、完全に遅れた (12/23 23:09) - ^ Tomić, Maja Katarina; Martinez, Marijana; Vrbanec, Tedo (2013). "Emoticons". ยืนยันอีเมลแล้วที่. 1 (1): 41 – via Google Scholar.

- ^ "Muzicons.com – music sharing widget". Retrieved June 25, 2008.

- ^ "The Creators of Trillian and Trillian Pro IM Clients". Cerulean Studios. Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ High, Kamau (August 9, 2007). "MTV Combats 'Sucky' Relationships". adweek.com. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007.

- ^ a b c US 6987991, Nelson, Johnathon O., "Emoticon input method and apparatus", published 2006-01-17, assigned to Wildseed Ltd.

- ^ Schwartz, John (January 29, 2001). "Compressed Data; Don't Mind That Lawsuit, It's Just a Joke". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016.

- ^ STT (August 13, 2012). "Hymiölle ei saa tavaramerkkiä | Kotimaan uutiset". Iltalehti.fi. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "Tavaramerkkilehti" (PDF). Tavaramerkkilehti (10): 27–28. May 31, 2006. Retrieved June 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "Russian hopes to cash in on ;-)". BBC News. December 11, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ Hern, Alex (February 6, 2015). "Don't know the difference between emoji and emoticons? Let me explain". The Guardian.

To complicate matters, some emoji are also emoticons […] the emoji which depict emotive faces are separated out as "emoticons".

- ^ "22.9 Miscellaneous Symbols (§ Emoticons: U+1F600–U+1F64F)". The Unicode Standard: Core Specification (PDF). Version 13.0. Unicode Consortium. 2020. p. 866.

- ^ "📖 Emoji Glossary". emojipedia.org. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ "Emoticons" (PDF). The Unicode Consortium.

Further reading

[edit]- Asteroff, Janet (1988). "Appendix C: Face Symbols and ASCII Character Set". Paralanguage in Electronic Mail: A Case Study (PhD thesis). Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms International. pp. 221–228. OCLC 757048921.

- Bódi, Zoltán, and Veszelszki, Ágnes (2006). Emotikonok. Érzelemkifejezés az internetes kommunikációban (Emoticons: Expressing Emotions in the Internet Communication). Budapest: Magyar Szemiotikai Társaság.

- Dresner, Eli, and Herring, Susan C. (2010). "Functions of the Non-verbal in CMC: Emoticons and Illocutionary Force" (preprint copy). Communication Theory 20: 249–268.

- Walther, J. B.; D'Addario, K. P. (2001). "The impacts of emoticons on message interpretation in computer-mediated communication". Social Science Computer Review. 19 (3): 323–345. doi:10.1177/089443930101900307. ISSN 0894-4393. S2CID 16179750.

- Veszelszki, Ágnes (2012). Connections of Image and Text in Digital and Handwritten Documents. In: Benedek, András, and Nyíri, Kristóf (eds.): The Iconic Turn in Education. Series Visual Learning Vol. 2. Frankfurt am Main et al.: Peter Lang, pp. 97−110.

- Veszelszki, Ágnes (2015). "Emoticons vs. Reaction-Gifs: Non-Verbal Communication on the Internet from the Aspects of Visuality, Verbality and Time". In: Benedek, András − Nyíri, Kristóf (eds.): Beyond Words: Pictures, Parables, Paradoxes (series Visual Learning, vol. 5). Frankfurt: Peter Lang. 131−145.

- Wolf, Alecia (2000). "Emotional expression online: Gender differences in emoticon use". CyberPsychology & Behavior 3: 827–833.

- Savage, Jon (February 21, 2009). "A design for life". Design. The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 29, 2024. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- Churches, Owen; Nicholls, Mike; Thiessen, Myra; Kohler, Mark; Keage, Hannah (January 6, 2014) [2013-07-17, 2013-12-05]. "Emoticons in mind: An event-related potential study". Social Neuroscience. 9 (2): 196–202. doi:10.1080/17470919.2013.873737. PMID 24387045.