Battle of Williamsburg

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

General Hooker's division engaging the rebels, Harper's Weekly | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,768[1] | 13,750 engaged (8,750 in reserve) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,682[2] | ||||||

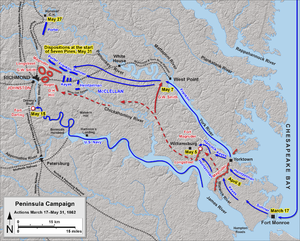

The Battle of Williamsburg, also known as the Battle of Fort Magruder, took place on May 5, 1862, in York County, James City County, and Williamsburg, Virginia, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was the first pitched battle of the Peninsula Campaign, in which nearly 41,000 Federals and 32,000 Confederates were engaged, fighting an inconclusive battle that ended with the Confederates continuing their withdrawal.

Following up the Confederate retreat from Yorktown, the Union division of Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker encountered the Confederate rearguard near Williamsburg. Hooker assaulted Fort Magruder, an earthen fortification alongside the Williamsburg Road, but was repulsed. Confederate counterattacks, directed by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, threatened to overwhelm the Union left flank, until Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny's division arrived to stabilize the Federal position. Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's brigade then moved to threaten the Confederate left flank, occupying two abandoned redoubts. The Confederates counterattacked unsuccessfully. Hancock's localized success was not exploited. The Confederate army continued its withdrawal during the night in the direction of Richmond, Virginia.[1]

Background

[edit]When Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston unexpectedly withdrew his forces from the Warwick Line at the Siege of Yorktown the night of May 3, Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan was taken by surprise and was unprepared to mount an immediate pursuit. On May 4, he ordered cavalry commander Brig. Gen. George Stoneman to pursue Johnston's rearguard and sent approximately half of his Army of the Potomac along behind Stoneman, under the command of Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner. He also ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin's division to board transport ships on the York River in an attempt to move upstream and land so as to cut off Johnston's retreat. However, it took two days just to board the men and equipment onto the ships, so the maneuver had no effect on the battle of May 5; Franklin's division landed and fought in the Battle of Eltham's Landing on May 7.[3]

By May 5, Johnston's army was making slow progress on muddy roads and Stoneman's cavalry was skirmishing with Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry, Johnston's rearguard. To give time for the bulk of his army to get free, Johnston detached part of his force to make a stand at a large earthen fortification, Fort Magruder, straddling the Williamsburg Road (from Yorktown), constructed earlier by Brig. Gen. John B. Magruder.[4]

Opposing forces

[edit]| Opposing Commanders at Williamsburg |

|---|

|

Union

[edit]Confederate

[edit]Battle

[edit]

Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker's 2nd division of the III Corps was the lead infantry in the Union Army advance. It assaulted Fort Magruder and a line of rifle pits and smaller fortifications that extended in an arc south-west from the fort, but was repulsed. Confederate counterattacks, directed by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, threatened to overwhelm Hooker's division, which had contested the ground alone since the early morning while waiting for the main body of the army to arrive. Hooker had expected Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith's 2nd Division of the IV Corps, marching north on the Yorktown Road, to hear the sound of battle and come in on Hooker's right in support. However, Smith had been halted by Sumner more than a mile away from Hooker's position. He had been concerned that the Confederates would leave their fortifications and attack him on the Yorktown Road.[5]

Longstreet's men did leave their fortifications, but they attacked Hooker, not Smith or Sumner. The brigade of Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox applied strong pressure to Hooker's line. Regimental bands playing Yankee Doodle slowed the retreating troops as they passed by, allowing them to rally long enough to be aided by the arrival of Brig. Gen. Philip Kearny's 3rd Division of the III Corps at about 2:30 p.m. Kearny ostentatiously rode his horse out in front of his picket lines to reconnoiter and urged his men forward by flashing his saber with his only arm. The Confederates were pushed off the Lee's Mill Road and back into the woods and the abatis of their defensive positions. There, sharp firefights occurred until late in the afternoon.[6]

While Hooker continued to confront the Confederate forces in front of Fort Magruder, Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's 1st Brigade of Baldy Smith's division, which had marched a few miles to the Federal right and crossed Cub's Creek at the point where it was dammed to form the Jones' Mill pond, began bombarding Longstreet's left flank around noon. Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill, commanding Longstreet's reserve force, had previously detached a brigade under Brig. Gen. Jubal Early and posted them on the grounds of the College of William and Mary. Hearing the sounds of Union artillery, Early and Hill hurried in that direction. Splitting his command, Early led two of his four regiments (the 24th and 38th Virginia Infantry) through the woods without performing adequate reconnaissance and found that they emerged not on the enemy's flank, but directly in front of Hancock's guns, which occupied two abandoned redoubts. He personally led the 24th Virginia Infantry on a futile assault and was wounded by a bullet through the shoulder, putting him out of action for almost two months. Also (per Longstreet's report of the battle) temporarily assigned to Early's brigade was the 2nd Mississippi Battalion and the 2nd Florida Infantry from Robert Rodes's brigade. The commander of the 2nd Florida, Col. George Ward, was killed leading a charge. Also killed in action were Lt. Col Thomas Irby of the 8th Alabama and Col. Christopher Mott of the 19th Mississippi. A.P. Hill's brigade of four Virginia regiments suffered severe losses in the fighting and three of its regimental commanders were wounded. Present on the field but unengaged or only involved in skirmishing or long range shooting were the divisions of Magruder and the remainder of Hill's division.[7]

Hancock had been ordered repeatedly by Sumner to withdraw his command back to Cub Creek, but he used the Confederate attack as an excuse to hold his ground. As the 24th Virginia charged, D.H. Hill emerged from the woods leading one of Early's other regiments, the 5th North Carolina. He ordered an attack before realizing the difficulty of his situation—Hancock's 3,400 infantrymen and eight artillery pieces significantly outnumbered the two attacking Confederate regiments, fewer than 1,200 men with no artillery support. He called off the assault after it had begun, but Hancock ordered a counterattack. The North Carolinians suffered 302 casualties, the Virginians 508. Union losses were about 100. After the battle, the counterattack received significant publicity as a major, gallant bayonet charge and McClellan's description of Hancock's "superb" performance gave him the nickname, "Hancock the Superb."[8]

At about 2:00 p.m., Brig. Gen. John J. Peck's brigade of Brig. Gen. Darius N. Couch's 1st Division of the IV Corps arrived to support and extend the right of Hooker's line, which had, by this stage, been pushed back from the cleared ground in front of Fort Magruder into the abatis and heavy wood about 600 – 1,000 yards (910 m) from the Confederate fortifications. The morale of Hooker's troops had been affected terribly by the loss of Captain Charles H. Webber's Battery "H" of the 1st U.S. Light Artillery and Captain Walter M. Bramhall's 6th Battery of the New York Light Artillery. Peck's arrival on the field and his brigade's recovery of Bramhall's battery came at a critical moment for Hooker's division, which was on the verge of retreat. Three Union regimental commanders were wounded in the battle and Col. William Dwight of the 70th New York Infantry was left behind on the field and captured by the Confederates. One regimental commander (Lt. Col John Van Leer of the 6th New Jersey) was killed in action.

Aftermath

[edit]The Northern press portrayed the battle as a victory for the Federal army. McClellan miscategorized it as a "brilliant victory" over superior forces. However, the defense of Williamsburg was seen by the South as a means of delaying the Federals, which allowed the bulk of the Confederate army to continue its withdrawal toward Richmond. Confederate casualties, including the cavalry skirmishing on May 4, were 1,682. Union casualties were 2,283.[2]

Battlefield preservation

[edit]Much of the battlefield has been lost to development, but the American Battlefield Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved more than 343 acres (1.39 km2) of the battlefield from 2010 to mid-2023.[9] This total includes the purchase of a 29-acre parcel on the battlefield that the Trust bought in December 2020.[10] In February 2023, the Trust announced the preservation of a 245-acre plot on the battlefield for $9.4 million, which it said was the second most expensive private battlefield land acquisition in American history.[11]

See also

[edit]- Troop engagements of the American Civil War, 1862

- Peninsula Campaign and Siege of Yorktown (1862)

- List of costliest American Civil War land battles

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d NPS Williamsburg (2002).

- ^ a b Sears (1992), p. 82.

- ^ Sears (1992), pp. 66–70.

- ^ Sears (1992), p. 70.

- ^ Salmon (2001), p. 82.

- ^ Salmon (2001), p. 82; Sears (1992), pp. 74–78.

- ^ Sears (1992), pp. 78–80.

- ^ Sears (1992), pp. 79–83.

- ^ ABT, Williamsburg Battlefield (2024).

- ^ AP Williamsburg battlefield land purchased for preservation (2020).

- ^ Feser (2022).

Sources

[edit]- Salmon, John S. (2001). The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2868-4.

- Sears, Stephen W. (1992). To the Gates of Richmond : the Peninsula Campaign (PDF) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields. pp. 39, 42, 58. ISBN 978-0-89919-790-6. LCCN 92006923. OCLC 231474432. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

- "Williamsburg (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2002. Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved January 19, 2003.

- "Williamsburg Battlefield". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. October 5, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- "Williamsburg battlefield land purchased for preservation". Associated Press. December 25, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- Feser, Molly (February 20, 2022). "Preservationists Take Steps to Finalize Protection of 245-Acre Williamsburg Battlefield Property". Williamsburg Yorktown Daily. Retrieved May 17, 2023.

Memoirs and primary sources

[edit]- Robert Underwood Johnson, Clarence Clough Buell, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Volume 2 (Pdf), New York: The Century Co., 1887.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

[edit]- Burton, Brian K. The Peninsula & Seven Days: A Battlefield Guide. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8032-6246-1.

- Dubbs, Carol K. Defend This Old Town: Williamsburg During The Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8071-3017-6.

- Sears, Stephen W. (1988). George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon (PDF) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Ticknor & Fields. pp. 95, 168–169. ISBN 978-0-544-39122-2. LCCN 88002138. OCLC 571245090. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Battle of Williamsburg, histories, photos, and preservation news (Civil War Trust)

- Virginia Civil War Traveler map

- Gruber, D. A. "The Battle of Williamsburg." Encyclopedia Virginia. Accessed October 30, 2014.

- Ricker, Harry H., III. Battle of Williamsburg — Detailed strategic and tactical description