The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars

| The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 16 June 1972[a] | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio | Trident, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 38:29 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars | ||||

| ||||

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (often shortened to Ziggy Stardust[1]) is the fifth studio album by the English musician David Bowie, released on 16 June 1972 in the United Kingdom through RCA Records. It was co-produced by Bowie and Ken Scott and features Bowie's backing band the Spiders from Mars — Mick Ronson (guitar), Trevor Bolder (bass) and Mick Woodmansey (drums). It was recorded from November 1971 to February 1972 at Trident Studios in London.

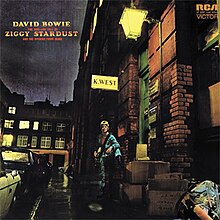

Described as a loose concept album and rock opera, Ziggy Stardust focuses on Bowie's titular alter ego Ziggy Stardust, a fictional androgynous and bisexual rock star who is sent to Earth as a saviour before an impending apocalyptic disaster. In the story, Ziggy wins the hearts of fans but suffers a fall from grace after succumbing to his own ego. The character was inspired by numerous musicians, including Vince Taylor. Most of the album's concept was developed after the songs were recorded. The glam rock and proto-punk musical styles were influenced by Iggy Pop, the Velvet Underground and Marc Bolan. The lyrics discuss the artificiality of rock music, political issues, drug use, sexuality and stardom. The album cover, photographed in monochrome and recoloured, was taken in London outside the home of furriers "K. West".

Preceded by the single "Starman", Ziggy Stardust reached top five of the UK Albums Chart. Critics responded favourably; some praised the musicality and concept while others struggled to comprehend it. Shortly after its release, Bowie performed "Starman" on Britain's Top of the Pops in early July 1972, which propelled him to stardom. The Ziggy character was retained for the subsequent Ziggy Stardust Tour, performances from which have appeared on live albums and a concert film. Bowie described the follow-up album, Aladdin Sane, as "Ziggy goes to America".

In later decades, Ziggy Stardust has been considered one of Bowie's best works, appearing on numerous professional lists of the greatest albums of all time. Bowie had ideas for a musical based on the album, although this project never came to fruition; ideas were later used for Diamond Dogs (1974). Ziggy Stardust has been reissued several times and was remastered in 2012 for its 40th anniversary. In 2017, it was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress, being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Background

[edit]After his promotional tour of America in February 1971,[2] David Bowie returned to Haddon Hall in England and began writing songs,[3] many of which were inspired by the diverse musical genres that were present in America.[4] He wrote over three dozen songs, many of which would appear on his fourth studio album Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust;[5] among these were "Moonage Daydream" and "Hang On to Yourself", which he recorded with his short-lived band Arnold Corns in February 1971,[6] and subsequently reworked for Ziggy Stardust.[3][5]

Hunky Dory was recorded in the middle of 1971 at Trident Studios in London,[7] with Ken Scott producing.[3] The sessions featured the musicians who would later become known as the Spiders from Mars – the guitarist Mick Ronson, the bassist Trevor Bolder, and the drummer Mick Woodmansey.[8] According to Woodmansey, Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust were almost recorded back-to-back, but the Spiders realised that most of the songs on Hunky Dory were not suitable live material, so they needed a follow-up album with material they could use on tour.[9]

After Bowie's manager Tony Defries ended his contract with Mercury Records, Defries presented the album to multiple labels in the US, including New York City's RCA Records. The head of the label, Dennis Katz, heard the tapes and saw the potential of the piano-based songs, signing Bowie to a three-album deal in September 1971; RCA became Bowie's label for the rest of the decade.[10][11] Hunky Dory was released in December to very positive reviews from critics but sold poorly.[12]

Recording and production

[edit]

The first song to be properly recorded for Ziggy Stardust was the Ron Davies cover "It Ain't Easy", on 9 July 1971. Originally slated for release on Hunky Dory, the song was passed for inclusion on that album and subsequently placed on Ziggy Stardust. With Hunky Dory being readied for release, the sessions for Ziggy Stardust officially began at Trident on 8 November 1971,[13] using the same personnel as Hunky Dory minus Wakeman. In 2012, Scott said that "95 percent of the vocals on the four albums I did with him as producer, they were first takes."[14] According to the biographer Nicholas Pegg, Bowie's "sense of purpose" during the sessions was "decisive and absolute"; he knew exactly what he wanted for each individual track. Since most of the tracks were recorded almost entirely live, Bowie recalled that at some points, he had to hum Ronson's solos to him.[15] Due to Bowie's generally dismissive attitude during the sessions for The Man Who Sold the World (1970),[16][3] Ronson had to craft his solos individually and had very little guidance.[15] Bowie had a much better attitude when recording Hunky Dory[3][16] and Ziggy Stardust, and gave Ronson guidance on what he was looking for.[15] For the album, Ronson used an electric guitar plugged to a 100-watt Marshall amplifier and a wah-wah pedal;[14] Bowie played acoustic rhythm guitar.[17]

On 8 November 1971, the band recorded initial versions of "Star" (then titled "Rock 'n' Roll Star") and "Hang On to Yourself", both of which were deemed unsuccessful. Both songs were rerecorded three days later on 11 November, along with "Ziggy Stardust", "Looking For a Friend", "Velvet Goldmine", and "Sweet Head".[18][15] The next day the band recorded two takes of "Moonage Daydream", one of "Soul Love", two of "Lady Stardust", and two of a new version of The Man Who Sold the World track "The Supermen". Three days later on 15 November, the band recorded "Five Years" as well as unfinished versions of "It's Gonna Rain Again" and "Shadow Man".[18][19] Woodmansey described the recording process as very fast-paced. He said they would record the songs, listen to them, and if they did not capture the sound they were looking for, record them again.[15] On that day a running order was created, which included the Chuck Berry cover "Around and Around" (titled "Round and Round"), the Jacques Brel cover "Amsterdam", a new recording of "Holy Holy", and "Velvet Goldmine". "It Ain't Easy" was absent from the list.[18] According to Pegg, the album was to be titled Round and Round as late as 15 December.[15]

After the 15 November session the group took a break for the holiday season.[15] Reconvening on 4 January 1972, the band held rehearsals for three days at Will Palin's Underhill Studios in Blackheath, London, in preparation for the final recording sessions.[20] After recording some of the new songs for radio presenter Bob Harris's Sounds of the 70s as the newly dubbed Spiders from Mars in January 1972,[20] the band returned to Trident that month to begin work on "Suffragette City" and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide".[15] After receiving a complaint from the RCA executive Dennis Katz that the album did not contain a single, Bowie wrote "Starman", which replaced "Round and Round" on the track listing at the last minute.[21] According to biographer Kevin Cann, the replacement occurred on 2 February. Two days later, the band recorded "Starman",[b] "Suffragette City", and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide"[23] bringing the sessions to a close.[14]

Concept and themes

[edit]Overview

[edit][Ziggy Stardust] was never discussed as a concept album from the start ... We were recording a bunch of songs—some of them happened to fit together, some didn't work.[24]

—Ken Scott on the Ziggy Stardust concept

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars is about a bisexual alien rock superstar named Ziggy Stardust.[25][26] It was not initially conceived as a concept album; much of the story was written after the album was recorded.[27][28] Tracks rewritten for the narrative included "Star" (originally titled "Rock 'n' Roll Star"),[28] "Moonage Daydream",[29] and "Hang On to Yourself".[30] Some reviewers have categorised the record as being a rock opera,[31][32][33] although Paul Trynka argues that it is less an opera and more a "collection of snapshots thrown together and later edited into a sequence that makes sense."[34] The characters were androgynous. Mick Woodmansey said the clothes they had worn had "femininity and sheer outrageousness". He also said that the characters' looks "definitely appealed to our rebellious artistic instincts".[35] Nenad Georgievski of All About Jazz said the record was presented with "high-heeled boots, multicolored dresses, extravagant makeup and outrageous sexuality".[36] Bowie had already developed an androgynous appearance, which was approved by critics, but received mixed reactions from audiences.[37]

The album's lyrics discuss the artificiality of rock music in general, political issues, drug use, sexual orientation, and stardom.[38][17] Stephen Thomas Erlewine described the lyrics as "fractured, paranoid" and "evocative of a decadent, decaying future".[26] Apart from the narrative, "Star" reflects Bowie's idealisations of becoming a star himself and shows his frustrations at not having fulfilled his potential.[39] On the other hand, "It Ain't Easy" has nothing to do with the overarching narrative.[28][40] The outtakes "Velvet Goldmine" and "Sweet Head" did fit the narrative, but both contained provocative lyrics, which likely contributed to their exclusions.[41][42] Meanwhile "Suffragette City" contains a false ending, followed by the phrase "wham bam, thank you, ma'am!"[43][44] Bowie uses American slang and pronunciations throughout, such as "news guy", "cop" and "TV" (instead of "newsreader", "policeman", and "telly" respectively).[45][46] Richard Cromelin of Rolling Stone called Bowie's imagery and storytelling in the track some of his most "adventuresome" up to that point,[44] while James Parker of The Atlantic wrote that Bowie is "one of the most potent lyricists in rock history".[32]

Inspirations

[edit]

One of the main inspirations for Ziggy Stardust was the English singer Vince Taylor, whom Bowie met after Taylor had a mental breakdown and believed himself to be a cross between a god and an alien.[47] Iggy Pop, the singer of the proto-punk band the Stooges,[48] provided another main inspiration. Bowie had recently become infatuated with the singer and took influence from him for his next record, both musically and lyrically.[49] Other influences for the character included Bowie's earlier album The Man Who Sold the World,[48] Lou Reed, the singer and guitarist of the Velvet Underground;[48] Marc Bolan, the singer and guitarist of the glam rock band T. Rex;[15][26] and the cult musician Legendary Stardust Cowboy.[50] An alternative theory is that during a tour, Bowie developed the concept of Ziggy as a melding of the persona of Iggy Pop with the music of Reed, producing "the ultimate pop idol".[37][15] Woodmansey also cited the guitarist and singer Jimi Hendrix and the progressive rock band King Crimson as being influences.[51]

Sources for the Ziggy Stardust name included the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, the song "Stardust" by Hoagy Carmichael, and Bowie's fascination with glitter.[34] A girlfriend recalled Bowie "scrawling notes on a cocktail napkin about a crazy rock star named Iggy or Ziggy", and on his return to England he declared his intention to create a character "who looks like he's landed from Mars".[37] In 1990, Bowie explained that the "Ziggy" part came from a tailor's shop called Ziggy's that he passed on a train. He liked it because it had "that Iggy [Pop] connotation but it was a tailor's shop, and I thought, Well, this whole thing is gonna be about clothes, so it was my own little joke calling him Ziggy. So Ziggy Stardust was a real compilation of things."[52][53] He later asserted that Ziggy Stardust was born out of a desire to move away from the denim and hippies of the 1960s.[54]

In 2015, Tanja Stark proposed that due to Bowie's well-known fascination with esoterica and his self-identification as 'Jungian', the Ziggy character may be a neologism influenced by Carl Jung, Greek and Gnostic concepts of Syzygy with their connotations of androgyny, the conjunction of male and female, and union of celestial bodies "hinting perhaps, at 'Syzygy' Stardust as futuristic alchemical theatre... foreshadow[ing] the double-headed mannequin of 'Where Are We Now?' (2013)".[55]

Story

[edit]The album begins with "Five Years"; a news broadcast reveals that the Earth only has five years left before it gets destroyed by an impending apocalyptic disaster.[45][56] The first two verses are from the point of view of a child hearing this news for the first time and going numb as it sinks in. The listener is addressed directly by the third verse, while the character of Ziggy Stardust is introduced indirectly.[57] Afterwards the listener hears the point of view of numerous characters dealing with love before the impending disaster ("Soul Love").[58] Biographer Marc Spitz called attention to the sense of "pre-apocalypse frustration" in the track.[57] Doggett said that following the "panoramic vision" of "Five Years", "Soul Love" offers a more "optimistic" landscape, with bongos and acoustic guitar indicating "mellow fruitfulness."[59] Ziggy directly introduces himself in "Moonage Daydream", where he proclaims himself "an alligator" (strong and remorseless), "a mama-papa" (non-gender specific), "the space invader" (alien and phallic), "a rock 'n' rollin' bitch", and a "pink-monkey-bird" (gay slang for a recipient of anal sex).[60][61]

"Starman" sees Ziggy bringing a message of hope to Earth's youth through the radio, salvation by an alien 'Starman', told from the point of view of one of the youths who hears Ziggy.[28] "Lady Stardust" presents an unfinished tale with what Doggett states as "no hint at a denouement beyond a vague air of melancholy".[62] Ziggy is recalled by the audience using both 'he' and 'she' pronouns, showing a lack of gender distinction.[28][62] Ziggy then looks at himself through a mirror, pondering what it would be like to make it "as a rock 'n' roll star" and if it would all be "worthwhile" ("Star").[28][39] In "Hang On to Yourself", Ziggy is put in front of the crowd. The track emphasises the metaphor that rock music goes from sex to fulfilment and back to sex again; Ziggy plans to abandon the sexual climax for a chance at stardom, which ultimately leads to his downfall.[28][30]

"Ziggy Stardust" is the central piece of the narrative, presenting a complete "birth-to-death chronology" of Ziggy.[62] He is described as a "well-hung, snow white-tanned, left-hand guitar-playing man" who rises to fame with his backing band the Spiders from Mars, but he lets his ego take control of him, effectively alienating his fans and losing his bandmates.[63] Unlike "Lady Stardust", "Ziggy Stardust" shows the character's rise and fall in a very human manner.[64] O'Leary notes that the song's narrator is not definitive: it could be an audience member retrospectively discussing Ziggy, it could be one of the Spiders or even the "dissociated memories" of Ziggy himself.[28] After his fall from grace, Ziggy is described by Pegg as "a hollow figure caught in the headlights of braking cars as he stumbles across the road."[65] Rather than dying in blood, Ziggy cries to the audience ("Rock 'n' Roll Suicide"), requesting they "give him their hands" because they are "wonderful" before perishing on stage.[63][65]

Musical styles

[edit]

The music on Ziggy Stardust has been retrospectively described as glam rock and proto-punk.[17][66][67] Georgievski felt the record represents Bowie's interests in "theater, dance, pantomime, kabuki, cabaret, and science fiction".[36] The Library of Congress also notes the presence of blues, garage rock, soul, and stadium rock.[68] Some of the tracks also feature elements of 1950s rock and pop ("Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" and "Sweet Head"),[28][69] pop and jazz ("Soul Love"),[57] heavy metal ("Moonage Daydream") and late-1970s punk rock ("Hang On to Yourself").[17] Bowie himself compared the record's sound to the music of Iggy Pop.[18] Author James Perone opined that the music is "more focused" than Bowie's previous works, being full of melodic and harmonic hooks.[17]

After the departure of Rick Wakeman on keyboards, the songs on Ziggy Stardust are considerably less piano-led than the songs on Hunky Dory and are more guitar-led, primarily due to the influence of Ronson's guitar and string arrangements.[15] Nevertheless, biographers have noted stylistic similarities to Hunky Dory in "Velvet Goldmine" and the string arrangement for "Starman".[28][70] Ronson played piano on the album as well as guitar and strings; according to Pegg, his playing on tracks like "Five Years" and "Lady Stardust" foreshadows the skills he showcases on Lou Reed's Transformer (1972).[15] Meanwhile his electric guitar playing dominates tracks including "Moonage Daydream",[28][60] "It Ain't Easy",[71] "Ziggy Stardust",[57] and "Suffragette City".[67] Additionally Bowie's acoustic guitar playing is prominent on some tracks, notably "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide". Perone argues that although listeners tend to pay closer attention to Ronson's electric, Ziggy Stardust is "one of the better albums" in Bowie's catalogue to highlight his rhythm guitar playing.[17]

The songwriting includes a wide variety of influences, from singer Elton John and poet Lord Alfred Douglas ("Lady Stardust"),[28][62][72] Little Richard ("Suffragette City"),[73][74][75] "Over the Rainbow" from the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz ("Starman"),[76] and the Velvet Underground ("Suffragette City" and "Velvet Goldmine").[73][77] As well as covering Chuck Berry's "Around and Around" during the sessions, Berry and Eddie Cochran influence the straightforward rock songs "Hang On to Yourself" and "Suffragette City".[78][17]

As well as including faster-paced numbers ("Star"),[39] the album contains the minimalist tracks "Five Years" and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide". Both tracks are mostly led by Bowie's voice,[78] building intensity throughout their runtimes.[79][80] While "Five Years" contains what author David Buckley calls a "heartbeat-like" drum beat,[81] "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" starts acoustic and builds to a lush arrangement, backed by an orchestra.[80] Pegg describes "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" as Bowie's own "A Day in the Life".[65] The album also features some experimentation. "Soul Love" contains bongos, a hand-clap rhythm, and a saxophone solo from Bowie which Doggett calls "relaxing".[17][82] "It Ain't Easy" features a harpsichord contribution from Rick Wakeman and backing vocals from Dana Gillespie, both of which were uncredited.[c][41] Additionally "Suffragette City" features one of Bowie's earliest uses of the ARP synthesiser, which later became the backbone of his late-1970s Berlin Trilogy.[75][74]

Artwork and packaging

[edit]The idea was to hit a look somewhere between the Malcolm McDowell thing with the one mascaraed eyelash and insects. It was the era of Wild Boys, by William S. Burroughs ... [It] was a cross between that and Clockwork Orange that really started to put together the shape and the look of what Ziggy and the Spiders were going to become ... Everything had to be infinitely symbolic.[84]

—Bowie discussing the album's packaging, 1993

The album cover photograph was taken by photographer Brian Ward in monochrome;[85] it was recoloured by illustrator Terry Pastor, a partner at the Main Artery design studio in Covent Garden with Bowie's longtime friend George Underwood. Both Ward and Underwood had done the artwork and sleeve for Hunky Dory.[15][86] The typography, initially pressed onto the original image using Letraset, was airbrushed by Pastor in red and yellow, and inset with white stars.[86] Pegg said that unlike many of Bowie's album sleeves, which feature close-ups of Bowie in a studio, the Ziggy image has Bowie almost in the foreground. Pegg describes the shot as: "Bowie (or Ziggy) [stands] as a diminutive figure dwarfed by the shabby urban landscape, picked out in the light of a street lamp, framed by cardboard boxes and parked cars".[15] Bowie is also holding a Gibson Les Paul guitar, which was owned by Arnold Corns guitarist Mark Pritchett and was the same guitar Pritchett used on Corns' recordings of "Moonage Daydream" and "Hang On to Yourself". Similar to Hunky Dory's cover, Bowie's jumpsuit and hair, which was still his natural brown at the time,[86] were artificially retinted. Pegg believes it gives the impression that the "guitar-clutching visitor" is from another dimension or world.[15]

The photograph was taken during a photoshoot on 13 January 1972 at Ward's Heddon Street studio in London, just off Regent Street. Suggesting they take photos outside before natural light was lost, the Spiders chose to stay inside while Bowie, who was ill with flu[87] went outside just as it started to rain. Not willing to go very far, he stood outside the home of furriers "K. West" at 23 Heddon Street.[88][89] According to Cann, the "K" stands for Konn, the surname of the company's founder Henry Konn, and the "West" indicated it was on the west end of London.[86] Soon after Ziggy Stardust became a massive success, the directors of K. West were displeased with their company's name appearing on a pop album. A solicitor for K. West wrote a letter to RCA saying: "Our clients are Furriers of high repute who deal with a clientele generally far removed from the pop music world. Our clients certainly have no wish to be associated with Mr. Bowie or this record as it might be assumed that there was some connection between our client's firm and Mr. Bowie, which is certainly not the case". However tensions eased and the company soon became accustomed to tourists photographing themselves on the doorstep.[86] K. West moved out of the Heddon Street location in 1991 and the sign was taken down; according to Pegg, the site remains a popular "place of pilgrimage" for Bowie fans.[15] Bowie said of the sign, "It's such a shame that sign [was removed]. People read so much into it. They thought 'K. West' must be some sort of code for 'quest.' It took on all these sort of mystical overtones".[84]

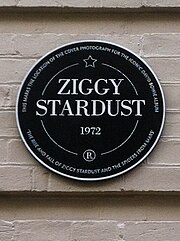

The rear cover of the original vinyl LP contained the instruction "To be played at maximum volume" (stylised in all caps). The cover was among the ten chosen by the Royal Mail for a set of "Classic Album Cover" postage stamps issued in January 2010.[15][90] In March 2012, The Crown Estate, which owns Regent Street and Heddon Street, installed a commemorative brown plaque at No. 23 in the same place as the "K. West" sign on the cover photo. The unveiling ceremony was attended by Woodmansey and Bolder; it was unveiled by Gary Kemp.[91] The plaque was the first to be installed by The Crown Estate and is one of few plaques in the country devoted to fictional characters.[92]

Release and promotion

[edit]Before Bowie changed his appearance to his Ziggy persona, he conducted an interview with journalist Michael Watts of Melody Maker where he came out as gay.[93] Published on 22 January 1972 with the headline "Oh You Pretty Thing",[94] the announcement garnered publicity in both Britain and America,[95] although according to Pegg the declaration was not as monumental as latter-day accounts perceive. Nevertheless Bowie was adopted as a gay icon in both countries, with Gay News describing him as "probably the best rock musician in Britain" and "a potent spokesman" for "gay rock". Although Defries was reportedly "shocked" by the announcement, Scott believed Defries was behind it from the start, wanting to use it for publicity.[15] According to Cann, the ambiguity surrounding Bowie's sexuality drew press attention for his tour dates, the upcoming album and the subsequent "John, I'm Only Dancing" non-album single.[95]

RCA released the lead single, "Starman", on 28 April 1972, backed by "Suffragette City".[28] The single sold steadily rather than spectacularly but earned many positive reviews. Promoting the upcoming album, Bowie, the Spiders, and keyboardist Nicky Graham performed the song on the Granada children's music programme Lift Off with Ayshea on 15 June; it was presented by Ayshea Brough.[70] Ziggy Stardust was released a day later in the United Kingdom on 16 June,[96][97][d][a] with the catalogue number SF 8287. It sold 8,000 copies in Britain in its first week and entered the top 10 in its second week on the UK Albums Chart.[15] The Lift Off performance was broadcast on 21 June in a "post-school" time slot, where it was witnessed by thousands of British children.[102] By 1 July, "Starman" rose to number 41 on the UK Singles Chart, earning Bowie an invitation to perform on the BBC television programme Top of the Pops.[103]

Bowie, the Spiders, and Graham performed "Starman" on Top of the Pops on 5 July 1972.[70] Bowie appeared in a brightly coloured rainbow jumpsuit, astronaut boots, and with "shocking" red hair while the Spiders wore blue, pink, scarlet, and gold velvet attire. During the performance, Bowie was relaxed and confident and wrapped his arm around Ronson's shoulder.[103] Shown the following day,[104] the performance brought public attention to the album[105] and helped solidify Bowie as a controversial pop icon. Buckley writes: "Many fans date their conversion to all things Bowie to this Top of the Pops appearance."[106] The performance was a defining moment for many British children.[107] U2 singer Bono said in 2010, "The first time I saw [Bowie] was singing 'Starman' on television. It was like a creature falling from the sky. Americans put a man on the moon. We had our own British guy from space–with an Irish mother."[108] After the performance,[107] "Starman" charted at number 10 in the UK while peaking at number 65 in the US.[109] On 11 April 1974,[110] impatient for a follow-up to "Rebel Rebel", RCA belatedly released "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" as a single. Buckley calls this move a "dosh-catching exercise".[111][112]

After dropping down the chart in late 1972, the album began climbing the chart again; by the end of 1972, the album had sold 95,968 units in Britain. It peaked at number five on the chart in February 1973.[113] In Canada, the album reached number 59 and was on the charts for 27 weeks.[114] In the US, the album peaked at number 75 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart in April 1973.[115] The album returned to the UK chart on 31 January 1981, peaking at No. 73,[116] amid the New Romantic era that Bowie had helped inspire.[117] After Bowie's death in 2016, the album reached a new peak of No. 21 in the US Billboard 200.[118] It has sold an estimated 7.5 million copies worldwide, making it Bowie's second-best-selling album after Let’s Dance (1983).[119]

Critical reception

[edit]After its release, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars received generally lukewarm reviews from contemporaneous critics.[120] James Johnson of New Musical Express (NME) said the album has "a bit more pessimism" than on previous releases and called the songs "fine".[121] Watts said in Melody Maker that while Ziggy Stardust had "no well-defined story line", it had "odd songs and references to the business of being a pop star that overall add up to a strong sense of biographical drama."[122] In Rolling Stone, writer Richard Cromelin thought the album was good, but he felt that it and its style might not be of lasting interest: "We should all say a brief prayer that his fortunes are not made to rise and fall with the fate of the 'drag-rock' syndrome."[44]

Some reviewers gave overwhelming praise to the album. A writer for Circus magazine wrote that the album is "from start to finish... of dazzling intensity and mad design", and called it a "stunning work of genius".[123] Referencing the album, Jack Lloyd of The Philadelphia Inquirer declared that "David Bowie is one of the most creative, compelling writers around today".[124] The Evening Standard's Andrew Bailey agreed, praising the songwriting, performances, production, and "operatic" music.[125] Robert Hilburn positively compared Ziggy to the Who's Tommy (1969) in the Los Angeles Times, describing the music as "exciting, literate and imaginative".[126]

Jon Tiven of Phonograph Record praised the album, calling it "the Aftermath of the Seventies", where there are no filler tracks. He further called Bowie "one of the most distinctive personalities in rock" believing that should Bowie ever become a star "of the Ziggy Stardust magnitude", he deserves it.[127] In Creem, Dave Marsh considered Ziggy Stardust Bowie's best record up to that point, stating "I can't see him stopping here for long".[128] Creem later placed the album at the top of their end of year list.[129] Meanwhile Lillian Roxon of New York Sunday News chose Ziggy Stardust over the Rolling Stones' Exile on Main St. as the best album of the year up to that point, even considering Bowie "the Elvis of the Seventies".[130]

Nevertheless the album did receive some negative reviews. A writer for Sounds magazine, who praised Hunky Dory, opined: "It would be a pity if this album was the one to make it... much of it sounds the work of a competent plagiarist."[131] Writing for The Times, Richard Williams felt that the persona was just for show and Bowie "doesn't mean it".[132] Although Nick Kent of Oz magazine enjoyed the album as a whole, he felt the character of Ziggy Stardust did not quite come together as well, stating that Bowie was "over-reaching himself".[133] Doggett said that this was the general verdict for reviewers who had enjoyed the "dense, philosophical songs" of Bowie's previous releases, as they could not relate to the "mythology" of Ziggy Stardust.[120]

Tour

[edit]

Bowie began touring as a promotion of Ziggy Stardust. The first part began in the United Kingdom and ran from 29 January to 7 September 1972.[134] A show at the Toby Jug pub in Tolworth on 10 February of the same year was hugely popular, catapulting him to stardom and creating, as described by Buckley, a "cult of Bowie".[135] Bowie retained the Ziggy character for the tour. His love of acting led to his total immersion in the characters he created for his music. After acting the same role over an extended period, it became impossible for him to separate Ziggy from his own offstage character. Bowie said that Ziggy "wouldn't leave me alone for years. That was when it all started to go sour... My whole personality was affected. It became very dangerous. I really did have doubts about my sanity."[136]

After arriving in America in September 1972, he told Newsweek magazine that he began having trouble differentiating between himself and Ziggy.[137] Fearing that Ziggy would define his career, Bowie quickly developed a new persona for his follow-up album, Aladdin Sane (1973), which was mostly recorded from December 1972 to January 1973 between legs of the tour.[138] Described by Bowie as "Ziggy goes to America", Aladdin Sane contained songs he wrote while travelling to and across America during the earlier part of the Ziggy tour. The character of Aladdin Sane was far less optimistic, rather engaging in aggressive sexual activities and heavy drugs. Aladdin Sane became Bowie's first number-one album in the UK.[139][140][141]

The tour lasted 18 months and passed through North America; it then went to Japan to promote Aladdin Sane.[140] The final date of the tour was 3 July 1973, which was performed at the Hammersmith Odeon in London. At this show, Bowie made the sudden surprise announcement that the show would be "the last show that we'll ever do", later understood to mean that he was retiring his Ziggy Stardust persona.[142][143] The performance was documented by filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker in a documentary and concert film, which premiered in 1979 and commercially released in 1983 as Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, with an accompanying soundtrack album titled Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture.[144][145][146] After being widely bootlegged, a show performed in Santa Monica, California, on 20 October 1972 was officially issued in 2008 as Live Santa Monica '72.[147][148]

Other projects

[edit]While recording Ziggy Stardust, Bowie offered "Suffragette City" to the band Mott the Hoople, who were on the verge of breaking up, but they declined. So Bowie wrote a new song for them, "All the Young Dudes".[23][74] With Bowie producing, the band recorded the track in May 1972.[149] Bowie would also produce the band's fifth album named after the song. Bowie would perform the song on the Ziggy Stardust Tour and record his own version during the Aladdin Sane sessions.[150] The tour took a toll on Bowie's mental health; it marked the beginning of his longtime cocaine addiction.[151] During this time, he underwent other projects that contributed to growing exhaustion. In August 1972, he co-produced Lou Reed's Transformer with Ronson in London in between tour commitments. Two months later, he mixed the Stooges' 1973 album Raw Power in Hollywood during the first US tour; Bowie had become friends with the band's frontman Iggy Pop.[152]

In November 1973, Bowie conducted an interview with the writer William S. Burroughs for Rolling Stone. He spoke of a musical based on Ziggy Stardust, saying: "Forty scenes are in it and it would be nice if the characters and actors learned the scenes and we all shuffled them around in a hat the afternoon of the performance and just performed it as the scenes come out." The musical, considered by Pegg a "retrograde step", fell through, but Bowie salvaged two songs for he had written for it—"Rebel Rebel" and "Rock 'n' Roll with Me"—for his 1974 album Diamond Dogs.[153]

Influence and legacy

[edit]The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars made [Bowie] a household name and left a milestone on the highway of popular music, rewriting the terms of the performer's contract with his audience and ushering in a new approach to rock's relationship with artifice and theatre that permanently altered the cultural aesthetic of the twentieth century.[15]

—Nicholas Pegg, 2016

Ziggy Stardust is widely considered to be Bowie's breakthrough album.[154][155][156] Although Pegg believes Ziggy Stardust was not Bowie's greatest work, he said that it had the biggest cultural impact of all his records.[15] Trynka stated that besides the music itself, the album "works overall as a drama that demands suspension of disbelief", making each listener a member of Ziggy's audience. He believes that decades later, "it's a thrill to be a part of the action."[157]

In retrospectives for The Independent and Record Collector, Barney Hoskyns and Mark Paytress respectively, said that unlike Bolan, who became a star a year before Bowie and influenced his glam persona of Ziggy Stardust, was unable to stay in a position of stardom in the long run due to a lack of adaptability. Bowie, on the other hand, made change a theme of his entire career, progressing through the 1970s with different musical genres, from the glam rock of Ziggy Stardust to the Thin White Duke of Station to Station (1976).[158][159] Hoskyns argued that through the Ziggy persona, Bowie "took glam rock to places that the Sweet only had nightmares about".[158] Ultimate Classic Rock's Dave Swanson stated that as the public were adapting to glam, Bowie decided to move on, abandoning the persona within two years.[107] Writing on Bowie's influence on the glam rock genre as a whole, Joe Lynch of Billboard called both Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane records that "ensured his long-term career and infamy". He argues that both albums "transcended" the genre, are "works of art", and are not just "glam classics", but "rock classics".[160] In 2002, Chris Jones of BBC Music argued that with the album, Bowie fashioned the template for the "truly modern pop star" that had yet to be matched.[161]

Before their formation, the members of English gothic rock band Bauhaus watched Bowie's performance of "Starman" on Top of the Pops, recalling that it was "a significant and profound turning point in their lives". The band thereafter idolised Bowie and subsequently covered "Ziggy Stardust" in 1982.[162] In 2004, Brazilian singer Seu Jorge contributed five cover versions of Bowie songs, three of them from Ziggy Stardust, to the soundtrack for the film The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.[163] Jorge later rerecorded the songs as a solo album called The Life Aquatic Studio Sessions. On that album's liner notes, Bowie wrote, "Had Seu Jorge not recorded my songs in Portuguese I would never have heard this new level of beauty which he has imbued them with."[164] In 2016, Jorge toured performing his Portuguese covers of Bowie's songs in front of sailboat-shaped screens.[165] Musician Saul Williams named his 2007 album The Inevitable Rise and Liberation of NiggyTardust! after the album.[166] In June 2017, an extinct species of wasp was named Archaeoteleia astropulvis after Ziggy Stardust ("astropulvis" is Latin for "stardust").[167][168]

Retrospective reviews

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B+[171] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[147] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Slant Magazine | |

| Spin | |

| Spin Alternative Record Guide | 8/10[176] |

| Uncut | |

Retrospectively, Ziggy Stardust has received critical acclaim and is recognised as one of the most important rock albums.[67][178][179] When reviewing the 30th anniversary edition of Ziggy Stardust in 2002, Daryl Easlea of Record Collector called the album "a monumental piece of work", praising the backing band of the Spiders and noting its cultural impact.[180] Jones noted the album's importance in rock music 30 years later and credits Scott and the Spiders as elements that elevated the album to the status it has received, finding it to be the "peak" of that group's creativity and achievements.[161] Billboard wrote that the record serves as a reminder to record companies that "hopelessly idiosyncratic and excessively provocative" music can initially be disliked but later celebrated as "timeless".[179] Writing for Slant Magazine in 2004, Barry Walsh said that aside from the "pop culture phenomenon" the album has become, the songs are among Bowie's finest and most memorable, and ultimately called the album "truly timeless".[156] Erlewine wrote for AllMusic: "Bowie succeeds not in spite of his pretensions but because of them, and Ziggy Stardust–familiar in structure, but alien in performance–is the first time his vision and execution met in such a grand, sweeping fashion."[26] Greg Kot writing for Chicago Tribune, described the album as a "guitar-fueled song cycle", saying it "enacted the deaths of Joplin, Morrison, Hendrix, and the '60s" and that it "presaged the dread, decadence and eroticism of a new era."[170]

Many reviewers have considered the album to be a masterpiece.[107][156][181] Reviewing its 40th anniversary, Jordan Blum of PopMatters writes: "It's easy to appreciate how Ziggy Stardust was a revolutionary record in 1972, and it's still as vibrant, significant, and enjoyably today."[67] In a 2013 readers' poll for Rolling Stone, Ziggy Stardust was voted Bowie's greatest album. The magazine argues that it "is the Bowie album that will be in history books".[182] Reviewing in 2015, Douglas Wolk of Pitchfork commented that while it has an incoherent concept overall, it still remains a great collection of tracks, "overflowing with huge riffs and huger personae".[147] Ian Fortnam wrote for Classic Rock in 2016 that "Ziggy Stardust is David Bowie's crowning achievement. Obviously, contrarians will insist other albums have proven to carry greater cultural weight or defined his artistic legacy better, but revisit Ziggy today and its visceral and emotional impact remains undeniable. Especially when played, as advised, 'at maximum volume'... Ziggy reflected and shaped its time and its audience like no other album".[63]

Rankings

[edit]The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars has frequently appeared on numerous lists of the greatest albums of all time by many publications. In 1987 as part of their 20th anniversary, Rolling Stone ranked it number six on "The 100 Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years".[183] In 1997, Ziggy Stardust was named the 20th greatest album of all time in a Music of the Millennium poll conducted in the UK.[184] It was voted number 11 and 27 in the second and third editions of English writer Colin Larkin's book All Time Top 1000 Albums, respectively. He said in the second edition: "The blend of rock star persona and alien creature defining Ziggy Stardust was probably [Bowie's] finest creation".[185] In 2003, Rolling Stone ranked it 35th on their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[186] It retained the same position on the updated 2012 list,[187] and was re-ranked 40th in 2020.[188] In 2004, it was placed at number 81 in Pitchfork's list of the 100 Best Albums of the 1970s,[189] while Ultimate Classic Rock included it in a similar list of the 100 best rock albums from the 1970s in 2015, calling it "a masterstroke of genius myth-making".[190] In 2006, Q magazine readers ranked it as the 41st best album ever,[191] while Time magazine chose it as one of the 100 best albums of all time.[192] In 2013, NME ranked the album 23rd in their list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, writing: "'Ziggy Stardust'... demands to be engaged with from start to finish".[193] In Apple Music's 2024 list of the 100 Best Albums, the album ranked number 24.[194]

The album was also included in the 2018 edition of Robert Dimery's book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[195] In March 2017, the album was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the United States National Recording Preservation Board, which designates it as a sound recording that has had significant cultural, historical, or aesthetic impact in American life.[68]

Reissues

[edit]Ziggy Stardust was first released on CD in November 1984 by RCA.[196] Dr. Toby Mountain later remastered the album at Northeastern Digital Recording in Southborough, Massachusetts[197] from the original master tapes for Rykodisc. The reissue was released on 6 June 1990, with five bonus tracks.[198] It charted for four weeks on the UK Albums Chart, peaking at number 25.[199] The album was remastered again by Peter Mew and released on 28 September 1999 by Virgin.[200]

On 16 July 2002, a two-disc version was released by EMI/Virgin. The first in a series of 30th Anniversary 2CD Editions, this release included a newly remastered version as its first CD. The second disc contained twelve tracks, most of which had been previously released on CD as bonus tracks on the 1990–1992 reissues. The new mix of "Moonage Daydream" was originally done for a 1998 Dunlop television commercial.[201]

On 4 June 2012, a "40th Anniversary Edition" was released by EMI/Virgin. This edition was remastered by original Trident Studios' engineer Ray Staff.[202] The 2012 remaster was made available on CD and on a special, limited edition format of vinyl and DVD, featuring the new remaster on an LP, together with 2003 remixes of the album by Scott (5.1 and stereo mixes) on DVD-Audio. The latter included bonus 2003 Scott mixes of "Moonage Daydream" (instrumental), "The Supermen", "Velvet Goldmine", and "Sweet Head".[196][203]

The 2012 remaster of the album and the 2003 remix (stereo mix only) were both included in the Parlophone box set Five Years (1969–1973), released on 25 September 2015.[204][205] The album with its 2012 remastering, was also rereleased separately in 2015–2016, in CD, vinyl, and digital formats.[206] Parlophone released the separate LP on 26 February 2016 on 180g vinyl.[207] On 16 June 2017, Parlophone reissued the album as a limited edition LP pressed on gold vinyl.[208]

On 17 June 2022, Parlophone reissued the album to celebrate its 50th anniversary, in vinyl picture disc and half-speed-mastered versions.[209][210] Two years later, the label announced the release of Waiting in the Sky, an alternate version of the album based on a tracklist made before the recording of "Starman", for Record Store Day 2024.[211] The same year, on 14 June 2024, Parlophone released a five-disc box set entitled Rock 'n' Roll Star!, chronicling Bowie's Ziggy Stardust period, featuring various unreleased tracks, including demos, outtakes and live performances.[212]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks written by David Bowie, except "It Ain't Easy", written by Ron Davies.[213]

Side one

- "Five Years" – 4:42

- "Soul Love" – 3:34

- "Moonage Daydream" – 4:40

- "Starman" – 4:10

- "It Ain't Easy" – 2:58

Side two

- "Lady Stardust" – 3:22

- "Star" – 2:47

- "Hang On to Yourself" – 2:40

- "Ziggy Stardust" – 3:13

- "Suffragette City" – 3:25

- "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" – 2:58

Personnel

[edit]Sources:[213][214][215][216][217]

- David Bowie – vocals, acoustic guitar, saxophone, string arrangements; pennywhistle on "Moonage Daydream"

- Mick Ronson – electric guitar, keyboards, backing vocals, string arrangements; autoharp on "Five Years"

- Trevor Bolder – bass guitar

- Woody Woodmansey – drums; congas on "Soul Love"

- Rick Wakeman – harpsichord on "It Ain't Easy" (uncredited)

- Dana Gillespie – backing vocals on "It Ain't Easy" (uncredited)

Technical

- David Bowie – production

- Ken Scott – production, audio engineering, mixing engineering

Charts and certifications

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

Decade-end charts[edit]

Sales and certifications[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Several sources indicate a release date of 6 June 1972.[101] In 2015, Bowie's official website discovered a contemporaneous letter from an RCA manager indicating the release date was 16 June.[96]

- ^ There are distinct mixes of "Starman". The original UK Ziggy Stardust album featured a "loud mix" of the "morse-code" piano-and-guitar section between the verse and the chorus. On the US release of the album, the "morse-code" section was lower in the mix.[22]

- ^ Gillespie's contribution to "It Ain't Easy" was credited for the 1999 reissue of the album.[83]

- ^ The US release date is unclear. The 27 May 1972 issue of Record World mentions that the album "is available" and the album appeared in the Billboard Bubbling Under the Top LP's chart at number 207 the week ending 10 June, suggesting a release date in late May.[98][99] Clerc lists it as 6 June.[100]

References

[edit]- ^ Perone 2007, p. 162.

- ^ Sandford 1997, pp. 72–74.

- ^ a b c d e Pegg 2016, pp. 340–350.

- ^ Greene, Andy (16 December 2019). "David Bowie's 'Hunky Dory': How America Inspired 1971 Masterpiece". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ^ a b Spitz 2009, p. 156.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 219.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (17 December 2016). "Revisiting David Bowie's First Masterpiece 'Hunky Dory'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ Woodmansey 2017, pp. 107, 117.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 195, 227.

- ^ Sandford 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 104.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 223, 230.

- ^ a b c Fanelli, Damian (23 April 2012). "On Its 40th Anniversary, 'Ziggy Stardust' Co-Producer Ken Scott Discusses Working with David Bowie". Guitar World. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Pegg 2016, pp. 351–360.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Perone 2007, pp. 26–34.

- ^ a b c d Cann 2010, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Woodmansey 2017, pp. 88, 114.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 262.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 263.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 242.

- ^ Trynka 2011, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Auslander 2006, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Woodmansey 2017, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m O'Leary 2015, chap. 5.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 253.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Nelson, Michael (5 November 2012). "Top 10 Rock Operas That Deserve A Stage Adaptation". Stereogum. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ a b Parker, James (April 2016). "The Brilliant Lyrics of David Bowie". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Auslander 2006, p. 138.

- ^ a b Trynka 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Woodmansey 2017, p. 123.

- ^ a b Georgievski, Nenad (21 July 2012). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (40th Anniversary Remaster)". All About Jazz. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b c Sandford 1997, pp. 73–74.

- ^ McLeod, Ken. "Space Oddities: Aliens, Futurism and Meaning in Popular Music". Popular Music. Vol. 22. JSTOR 3877579.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 260–261.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 132.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 298.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Cromelin, Richard (20 July 1972). "The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 130.

- ^ "BBC – BBC Radio 4 Programmes – Ziggy Stardust Came from Isleworth". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 September 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Ludwig, Jamie (13 January 2016). "David Bowie's Spirit of Transgression Made Him Metal Before Metal Existed". Noisey. Vice Media. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Trynka 2011, pp. 175–182.

- ^ Schinder & Schwartz 2008, p. 448.

- ^ Woodmansey 2017, p. 114.

- ^ Campbell 2005.

- ^ Bowie, David (25 August 2009). "David Bowie: the 1990 Interview". Paul Du Noyer (Interview). Interviewed by Paul Du Noyer. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011. In: "David Bowie". Q. No. 43. April 1990.

- ^ "David Bowie On The Ziggy Stardust Years: 'We Were Creating The 21st Century In 1971'". NPR. 19 September 2003. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ Stark, Tanja (22 June 2015). "Stark, T., Crashing out with Sylvian: David Bowie, Carl Jung and the Unconscious, in Deveroux, E., M.Power and A. Dillane (eds) David Bowie: Critical Perspectives: Routledge Press Contemporary Music Series. (chapter 5) Routledge Academic, 2015". www.tanjastark.com. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ Booth, Susan (2016). ""The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" — David Bowie (1972)" (PDF). The National Registry. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018 – via www.loc.gov.

- ^ a b c d Spitz 2009, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 253.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 162.

- ^ a b Pegg 2016, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d Doggett 2012, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c Fortnam, Ian (11 November 2016). "Every song on David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust ranked from worst to best". Louder. Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 325–326.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Inglis 2013, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Blum, Jordan (12 July 2012). "David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ a b "National Recording Registry Picks Are "Over the Rainbow"". Library of Congress. 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 261–263.

- ^ Raggett, Ned. "'It Ain't Easy' – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b Raggett, Ned. "'Suffragette City' – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Pegg 2016, pp. 271–272.

- ^ a b Owsinski, Bobby (11 January 2016). "The Making of David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust Album". Forbes. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 169.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 158.

- ^ a b Trynka 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 92–93, 227–228.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, pp. 161, 171.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 118.

- ^ Doggett 2012, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 223.

- ^ a b Sinclair, David (1993). "Station to Station". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ^ "Alternate Photos from David Bowie's 'Ziggy Stardust' Cover Shoot". Flavorwire. 23 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Cann 2010, p. 254.

- ^ Spitz 2009, p. 175.

- ^ Cann 2010, pp. 238–239, 254.

- ^ Kemp, Gary (27 March 2012). "How Ziggy Stardust Fell To Earth". London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ "Classic Album Covers: Issue Date – 7 January 2010". Royal Mail. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ Press Association (27 March 2012). "David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust album marked with blue plaque". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "Site of Ziggy Stardust album cover shoot marked with plaque". BBC News. 27 March 2012. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Watts, Michael (22 January 2006). "David Bowie tells Melody Maker he's gay". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Watts, Michael (22 January 1972). "Oh You Pretty Thing". Melody Maker. pp. 13–15 – via The History of Rock 1972.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b "Happy 43rd Birthday to Ziggy Stardust". David Bowie Official Website. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Jones 2017, p. S12.

- ^ Ross, Ron (27 May 1972). "Bowie Tempts Teens: New Album, Single". "Who in the World" (PDF). Record World. p. 23. Retrieved 5 October 2017 – via americanradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Billboard" (PDF). Billboard. 10 June 1972. p. 43. Retrieved 5 October 2017 – via americanradiohistory.com.

- ^ Clerc 2021, p. 137.

- ^

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Swanson, Dave (6 June 2017). "How David Bowie Created a Masterpiece with 'Ziggy Stardust'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- O'Leary 2015, chap. 5.

- Cann 2010, p. 252.

- Spitz 2009, p. 186.

- Pegg 2016, p. 360.

- Clerc 2021, p. 137.

- ^ Cann 2010, p. 256.

- ^ a b Cann 2010, p. 258.

- ^ "Bowie performs 'Starman' on 'Top of the Pops'". 7 Ages of Rock. BBC. 5 July 1972. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013.

- ^ Inglis 2013, p. 73.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 125–127.

- ^ a b c d Swanson, Dave (6 June 2017). "How David Bowie Created a Masterpiece with 'Ziggy Stardust'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Sheffield 2016, p. 70.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (1 November 2016). "David Bowie's Top 20 Biggest Billboard Hits". Billboard. Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Clerc 2021, p. 153.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 228, 780.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 213.

- ^ "David Bowie". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b "RPM Top 100 Albums - April 28, 1973" (PDF).

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel (2001). Top Pop Albums 1955–2001. Menomonee Falls: Record Research Inc. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-89820-147-5.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 75 – David Bowie". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 318.

- ^ "David Bowie". Billboard. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Dee, Johnny (7 January 2012). "David Bowie: Infomania". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ a b Doggett 2012, p. 173.

- ^ Johnson, James (3 June 1972). "Ziggy Stardust". New Musical Express. In: "David Bowie". The History of Rock 1972. pp. 12–15. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Watts, Michael (7 June 1972). "Ziggy Stardust". Melody Maker. In: "David Bowie". The History of Rock 1972. pp. 12–15. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Ziggy Stardust". Circus. June 1972.

- ^ Lloyd, Jack (16 July 1972). "David Bowie's Music Unsettles Chill". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 101. Retrieved 21 November 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Bailey, Andrew (1 July 1972). "Record Reviews – From space comes Ziggy: super star". Evening Standard. p. 14. Retrieved 29 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (17 September 1972). "Music to Go to College By". Los Angeles Times. p. 540. Retrieved 29 December 2021 – via Newspapers.com (subscription required).

- ^ Tiven, Jon (July 1972). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (RCA)". Phonograph Record. Retrieved 10 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Marsh, Dave (September 1972). "David Bowie: The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars (RCA)". Creem. Retrieved 9 May 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ "Albums of the Year". Creem. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Roxon, Lillian (18 June 1972). "David Bowie: The Elvis Of the Seventies". New York Sunday News. Retrieved 10 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Williams, Richard (2 September 1972). "Albums from David Bowie, T. Rex, Rod Stewart and Roxy Music". The Times. Retrieved 10 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Kent, Nick (July 1972). "David Bowie: The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders From Mars (RCA)". Oz. Retrieved 9 May 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 539.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Sandford 1997, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 175.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 361–363.

- ^ Sheffield 2016, pp. 81–86.

- ^ a b Sandford 1997, pp. 108.

- ^ Buckley 2005, p. 157.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 552–555.

- ^ Buckley 2005, pp. 165–167.

- ^ "Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". phfilms.com. Pennebaker Hegedus Films. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ Gibson, John (August 1979). "David Bowie Invited to Film Festival Premiere". Edinburgh Evening News.

- ^ "Theater Guide". New York. 30 January 1984. p. 63. Retrieved 3 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Wolk, Douglas (1 October 2015). "David Bowie: Five Years 1969–1973". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ Thornton, Anthony (1 July 2008). "David Bowie – 'Live: Santa Monica '72' review". NME. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 195.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 20.

- ^ Doggett 2012, p. 186.

- ^ Pegg 2016, pp. 482–485.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 368.

- ^ Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 52–56.

- ^ Bernard, Zuel (19 May 2012). "The rise and rise of Ziggy". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Walsh, Barry (3 September 2004). "MUSIC Review: David Bowie, The Rise & Fall Of Ziggy Stardust". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Trynka 2011, p. 483.

- ^ a b Hoskyns, Barney (15 June 2002). "David Bowie: Ziggy Stardust, now a man of wealth and taste". The Independent. Retrieved 10 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Paytress, Mark (June 1998). "Ziggy Stardust: The Album That Killed The Sixties". Record Collector. Retrieved 10 October 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Lynch, Joe (14 January 2016). "David Bowie Influenced More Musical Genres Than Any Other Rock Star". Billboard. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ a b Jones, Chris (2002). "David Bowie The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars Review". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Pettigrew, Jason (23 January 2018). "Goth Inventors Bauhaus Recall the Night They Met David Bowie". AltPress. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ Pegg 2016, p. 497.

- ^ Cobo, Leila (12 January 2016). "David Bowie Praised Seu Jorge for Taking His Songs to a 'New Level of Beauty' With Portuguese Covers: Listen". Billboard. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ "'The Life Aquatic' Actor Seu Jorge Plots David Bowie Covers Tour". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Saul Williams Covers U2, Talks NiggyTardust". Stereogum. 5 November 2007. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Ferreira, Becky (23 June 2017). "This Freaky 100-Million-Year-Old Wasp Was Named for David Bowie". Vice. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "'Star dust' wasp is a new extinct species named after David Bowie's alter ego". Science Daily. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Blender. No. 48. June 2006. Archived from the original on 23 August 2007. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (10 June 1990). "Bowie's Many Faces Are Profiled On Compact Disc". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Christgau 1981.

- ^ Larkin 2011.

- ^ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Q. No. 128. May 1997. pp. 135–136.

- ^ Sheffield 2004, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Dolan, Jon (July 2006). "How to Buy: David Bowie". Spin. Vol. 22, no. 7. p. 84. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ Sheffield 1995, p. 55.

- ^ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Uncut. No. 63. August 2002. p. 98.

- ^ "David Bowie on the Ziggy Stardust Years: 'We Were Creating The 21st Century In 1971'". NPR. 19 September 2003. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust & the Spiders From Mars (30th anniversary edition)". Billboard. 20 July 2002. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Easlea, Daryl (July 2002). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust And the Spiders From Mars: 30th Anniversary Edition". Record Collector. Retrieved 9 May 2021 – via Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- ^ Jarroush, Sami (8 July 2014). "Masterpiece Reviews: "David Bowie – The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars"". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ "Readers' Poll: The Best David Bowie Albums". Rolling Stone. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years". Rolling Stone. No. 507. August 1987. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "The music of the millennium". BBC. 24 January 1998. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Larkin 1998, p. 19; Larkin 2000, p. 47

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie". Rolling Stone. 2003. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie". Rolling Stone. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Picco, Judson (23 June 2004). "Top 100 Albums of the 1970s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Top 100 '70s Rock Albums". Ultimate Classic Rock. 5 March 2015. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Albums Ever". Q. No. 137. February 1998. pp. 37–79.

- ^ "The All-Time 100 Albums". Time. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ^ Barker, Emily (25 October 2013). "The 500 Greatest Albums Of All Time: 100–1". NME. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Apple Music 100 Best Albums". Apple. Archived from the original on 14 May 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (2018). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. London: Cassell. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-1-78840-080-0.

- ^ a b Griffin 2016

- ^ "Northeastern Digital home page". Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ "The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars [Bonus Tracks] – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ a b "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (1990 version)". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – David Bowie (1999 credits)". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Drake, Rossiter (4 September 2002). "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars: 30th Anniversary Edition". Metro Times. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Album Premiere: David Bowie's 'Ziggy Stardust' (Anniversary Remaster)". Rolling Stone. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Remastered Ziggy 40th Vinyl/CD/DVD Due in June". David Bowie Official Website. 21 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Five Years 1969 – 1973 box set due September". David Bowie Official Website. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (23 June 2015). "David Bowie to Release Massive Box Set 'Five Years 1969–1973'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 16 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ Sinclair, Paul (15 January 2016). "David Bowie / 'Five Years' vinyl available separately next month". Super Deluxe Edition. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016.

- ^ "180g vinyl Bowie albums due February". David Bowie Official Website. 27 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016.

- ^ "Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust gold vinyl due". David Bowie Official Website. 11 May 2017. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017.

- ^ Sinclair, Paul (28 April 2022). "David Bowie / Ziggy Stardust half-speed and picture disc". Super Deluxe Edition. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Ziggy Stardust 50th anniversary vinyl releases". David Bowie Official Website. 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Waiting in the Sky Vinyl LP for RSD 2024". David Bowie Official Website. 7 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- ^ Martoccio, Angie (22 March 2024). "This Summer, You Can Go Back to David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust Era With Massive Reissue". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 21 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars (liner notes). David Bowie. RCA Records. 1972. SF 8287.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars – Credits". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Cann 2010.

- ^ O'Leary 2015.

- ^ Pegg 2016.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2021). "David Bowie". Sisältää hitin - 2. laitos Levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla 1.1.1960–30.6.2021 (PDF) (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. pp. 36–37.

- ^ "UK Albums Charts 1972". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Go-Set Australian charts - 25 November 1972". www.poparchives.com.au.

- ^ Racca, Guido (2019). M&D Borsa Album 1964–2019 (in Italian). Amazon Digital Services LLC - Kdp Print Us. ISBN 978-1-0947-0500-2.

- ^ "Hits of the World – Spain". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 7 April 1973. p. 66. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "UK Albums Charts 1973". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2016. 8. hét". slagerlistak.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ "Top album Classifica settimanale WK 9". FIMI. 26 February 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ "Charts.nz – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Topp 40 Album 2016-03". VG-lista. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Hung Medien. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "UK Charts 2016". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "UK Vinyl Charts 2016". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "Billboard 200 01/30/2016". Billboard. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie Chart History (Top Catalog Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "David Bowie – Billboard". Billboard. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "UK Vinyl Charts 2017". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ "IFPI Charts". www.ifpi.gr. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ "Portuguese charts portal (24/2021)". portuguesecharts.com. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2022. 25. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ "Official IFPI Charts – Top-75 Albums Sales Chart (Week: 31/2024)". IFPI Greece. Archived from the original on 7 August 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ "Top US Billboard 200 Albums - Year End 1973". bestsellingalbums. Retrieved 17 September 2024.

- ^ "End of Year Album Chart Top 100 – 2016". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ "Official Top 100 biggest selling vinyl albums of the decade". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "Danish album certifications – David Bowie – Ziggy Stardust". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – David Bowie – Ziggy Stardust" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Lane, Daniel (9 March 2013). "David Bowie's Official Top 40 Biggest Selling Downloads revealed!". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "British album certifications – David Bowie – The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust". British Phonographic Industry.

- ^ "American album certifications – David Bowie – Ziggy Stardust". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Dee, Johnny (7 January 2012). "David Bowie: Infomania". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2016.}

Sources

[edit]- Auslander, Philip (2006). Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-47-206868-5.

- Buckley, David (2005) [First published 1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5.

- Campbell, Michael (2005). Popular music in America: the beat goes on. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-55534-4.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croydon, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). David Bowie: An Illustrated Record. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-77966-6.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). "David Bowie: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. ISBN 978-0-89919-026-6. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2015 – via robertchristgau.com.

- Clerc, Benoît (2021). David Bowie All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. New York City: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-0-7624-7471-4.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- Griffin, Roger (2016). David Bowie: The Golden Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85-712875-1.

- Inglis, Ian, ed. (2013). Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-40-949354-9.

- Jones, Dylan (2017). David Bowie: A Life. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-0-45149-783-3.

- Larkin, Colin (1998). All Time Top 1000 Albums (2nd ed.). London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0258-7.

- Larkin, Colin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0493-2.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). "Bowie, David". The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester, UK: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Perone, James E. (2007). The Words and Music of David Bowie. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-27-599245-3.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80854-8.

- Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (2008). Icons of Rock. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33846-5.