Abbeville

Abbeville

| |

|---|---|

Subprefecture and commune | |

![The belfry, entrance to the Boucher-de-Perthes Museum [fr]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9d/Mus%C3%A9e_Boucher-de-Perthes.jpg/164px-Mus%C3%A9e_Boucher-de-Perthes.jpg) The belfry, entrance to the Boucher-de-Perthes Museum | |

| Coordinates: 50°06′21″N 1°50′09″E / 50.1058°N 01.8358°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Hauts-de-France |

| Department | Somme |

| Arrondissement | Abbeville |

| Canton | Abbeville-1 Abbeville-2 |

| Intercommunality | Baie de Somme |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Pascal Demarthe[1] |

| Area 1 | 26.42 km2 (10.20 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[2] | 22,595 |

| • Density | 860/km2 (2,200/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Abbevillois, Abbevilloises |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 80001 /80100 |

| Elevation | 2–76 m (6.6–249.3 ft) (avg. 8 m or 26 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Abbeville (French: [abvil] ; West Flemish: Abbekerke; Picard: Advile) is a commune in the Somme department and in Hauts-de-France region in northern France.

It is the chef-lieu of one of the arrondissements of Somme. Located on the river Somme, it was the capital of Ponthieu.

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]

Abbeville is located on the river Somme, 20 km (12 mi) from its modern mouth in the English Channel. The majority of the town is located on the east bank of the Somme, as well as on an island.[3] It is located at the head of the Abbeville Canal, and is 45 km (28 mi) northwest of Amiens and approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) from Paris. It is also 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) as the crow flies from the Bay of Somme and the English Channel. In the medieval period, it was the lowest crossing point on the Somme and it was nearby that Edward III's army crossed shortly before the Battle of Crécy in 1346.

Just halfway between Rouen and Lille, it is the historical capital of the County of Ponthieu and maritime Picardy.

Quarters, hamlets and localities

[edit]- Émonville Park takes its name from one of its owners Arthur Foulc d'Émonville, an amateur botanist, who bought a part of the Priory of Saints Peter and Paul in order to accommodate a garden and to construct a mansion, which now houses the study and heritage section of the Robert Mallet municipal library. The remains of the priory include the entrance arch, current main entrance of the garden located on Place Clemenceau, as well as some buildings which make up the Saint-Pierre School, including the remarkable Chapel of Saint-Pierre-Saint-Paul (now in a very poor state). This place is considered by some to be the origin of Abbeville, because it was the location of the first château of the Counts of Ponthieu, called castrum. It is assumed that this place could have been the location of the farm of Abbatisvilla, dependent upon the Abbey of Saint-Riquier.[4]

- The suburbs of La Bouvaque and Thuison are located to the north of the city. The municipal park of La Bouvaque, bordered by the Boulevard de la République, consists of the La Bouvaque pond and Collart meadows, former settling ponds of the Béghin-Say sugar factory. It was in Thuison that the Carthusian monastery of Saint-Honoré was founded in 1301 by William of Mâcon, Bishop of Amiens.[5] This was a property of the Order of the Temple, sold to the latter by Gérard de Villars, the last master of the province of France.[6] The sale was confirmed by Hugues de Pairaud, then visitor of France.[7]

- The suburb of Saint Gilles

- Rouvroy is to the west, and the origin of the name comes from Rouvray (from Latin roborem, Middle French robre, meaning "oak") indicates the presence of an oak wood or a remarkable oak.

- Mautort, beside Rouvroy, is a former stronghold located between Cambron and Abbeville. It is at the origin of the noble name of de Mautort, surviving in the name of the Tillette de Mautort family or, for example, of Georges-Victor Demautort. The name tort is attested in Old French with the sense of détour and Mau (from the Latin malus, meaning "bad"). The Church of Saint-Silvin de Mautort, emblematic of the quarter, was initially a simple chapel of sailors founded in the 11th century and underwent many changes during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries.

- Menchecourt, in the north-west, is known for its sugar factory (closed in 2008 and demolished in 2010) and for its football club.

Transport

[edit]

Abbeville station is served by trains on the line between Boulogne-sur-Mer and Amiens and between Calais and Paris. Abbeville was the southern terminus of the Réseau des Bains de Mer, the line to Dompierre-sur-Authie opened on 19 June 1892 and closed on 10 March 1947.

Abbeville is located just near the A16 autoroute, and is about 1 hour 50 minutes by car from Paris.

Climate

[edit]Abbeville has an oceanic climate due to its proximity to the ocean.[citation needed] The summers and winters are temperate and rainy, days of snow are fairly common (18 days of snow per year on average). There are 26 days of storm per year with a maximum in the months of July and August, the rains are frequent and distributed regularly in the year with precipitation totalling 781.3 millimetres (30.76 in) and 128 days with precipitation. The sunshine is average (1678 hours of sunshine) because of its position in the north and the oceanic influence also helps to prevent temperatures from being too high with only three days of intense heat (temperature > = 30 °C) and from being too cold with 6 days of heavy frost (temperature = -5 °C). The highest temperature was 37.8 °C (100.0 °F) on 1 July 1952 and the record low is −17.4 °C (0.7 °F), which occurred during a particularly cold spell on 17 January 1985.

| Climate data for Abbeville, 1981–2010 except sun 1991–2010, records from 1921 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

19.9 (67.8) |

25.2 (77.4) |

29.3 (84.7) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.2 (95.4) |

41.3 (106.3) |

37.3 (99.1) |

32.8 (91.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

41.3 (106.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.2 (66.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.5 (40.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.4 (0.7) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 63.3 (2.49) |

49.3 (1.94) |

56.7 (2.23) |

52.5 (2.07) |

59.4 (2.34) |

66.0 (2.60) |

59.1 (2.33) |

70.2 (2.76) |

65.1 (2.56) |

81.7 (3.22) |

79.6 (3.13) |

79.7 (3.14) |

782.6 (30.81) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.4 | 9.4 | 11.5 | 10.1 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 9.1 | 9.2 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 128.0 |

| Average snowy days | 4.1 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 16.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 89 | 87 | 85 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 83 | 83 | 85 | 88 | 90 | 90 | 85.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.6 | 78.5 | 125.0 | 172.2 | 195.5 | 209.3 | 216.9 | 209.2 | 158.8 | 117.4 | 69.8 | 56.6 | 1,679.7 |

| Source 1: Meteo France[8][9] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity, snowy days 1961–1990)[10] | |||||||||||||

Demography

[edit]Its inhabitants are called Abbevillois in French.

Demographic evolution

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: EHESS[11] and INSEE[12] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Age structure

[edit]The population of the commune is relatively old.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Economy

[edit]Abbeville is the seat of the Chambre de commerce et d'industrie d'Abbeville – Picardie maritime. It manages ports, the aerodrome and industrial areas of the arrondissement of Abbeville.

Abbeville manufactured textiles, and in particular, linens and tablecloths when the Van Robais family created la Manufacture Royale des Rames in 1665;[citation needed] however after the Edict of Nantes was revoked and the subsequent migration of Protestants away from the area, the cloth business succumbed.[15] Also affecting the economy of the town was the closure of the river port on the Somme River due to excessive silt.[15] It also has cordage factories, carpet factories, and spinning mills. Finally, it also fabricates locks, has breweries, and produces food and, until 2007, sugar,[3][16][better source needed][15]

Culture, festivals, sport and leisure

[edit]Culture

[edit]

- The municipal theatre, built in 1911, registered as an historic monument in 2003

- The Municipal Conservatory of the Abbevillois (music and dance)

- The Robert Mallet municipal library: It preserves a Heritage fonds including being based on collections from the ancient monastic establishments in the vicinity, with 972 manuscripts. Among these, is a Carolingian Gospel book running to 790–800 at the Court of Charlemagne.[17]

- The Boucher de Perthes Museum, a certified Museum of France

- The Society of Emulation of Abbeville

Festivals

[edit]Floral town

[edit]Abbeville was awarded three flowers in 2007 by the Conseil des Villes et Villages Fleuris de France [Council of Floral Cities and Villages of France] in the Contest of floral cities and villages.[19]

Sport

[edit]- Association Futsal Abbevilloise

- Rowing club, Sport Nautique Abbevillois, Centre nautique Jean-Raymond-Peltier

- Rugby union club, XV of Abbeville, at stage Imanol Harinordoquy (side of Justice)

- Cycling club, the Étoile Cycliste Abbevilloise

- Handball club, the EAL Handball

- Table tennis club, currently in Nationale 1

- Flying school of aeroplanes and gliders, and ULM school (Ludair), located on the edge of Abbeville and Buigny-Saint-Maclou (at the Aerodrome Abbeville)

- Football, Sporting Club Abbeville Côte Picarde, a team of one of the regional football leagues

- Field hockey, women's team playing in Nationale 1

- Judo Club Abbevillois

- Grand-Laviers golf course, north-west of the city, one of the largest of Picardy and one of the cheapest of France[citation needed]

- Skatepark of Abbeville

- Boxing Club – Bobo-Lorcy and Benjamin-Leberton rooms

- Automotive Stadium of Abbeville

- Fencing club, Abbevilloise Fencing Association (AAE)

- Sporting club of swimming (SCA swimming)

Abbeville has featured as the departure point for Stage 4 of the 2012 Tour de France and the departure point for Stage 1 of the 2011 Tour de Picardie. The commune has also been on the route of the Grand Prix de la Somme one-day cycle race. Abbeville will feature as the departure point for Stage 6 of the 2015 Tour de France, on 9 July.

Games

[edit]- Chess club, Exchequer of Picardy Maritime (EPM).

- Poker club, (PCA Poker Club Abbeville), a club which has finished first at France's Team Poker Championships (CNEC).

In literature

[edit]Voltaire, in his Dictionnaire philosophique (1769), wrote an article Torture, in which he set out an account of the martyrdom of the Chevalier de La Barre:

When the Knight of La Barre, grandson of a lieutenant general of the armies, young man of great wit and great hope, but with the giddiness of unbridled youth, was convicted of having sung ungodly songs, and even to have passed before a procession of Capuchin without removing his hat, the judges of Abbeville, comparable to the Roman senators, ordered, not only that his tongue be torn out, his hand was cut off, and his body be burned slowly; but they still applied torture to find out how many songs he had sung, and how many processions he had seen pass the hat on the head. It wasn't in the 13th or 14th century that this adventure came, it was in the 18th.

Victor Hugo evoked the trips he made to Abbeville in his accounts of travel.

André Maurois, in Les Silences du Colonel Bramble (1918) amusingly described the intact commercial spirit of the inhabitants of Abbeville in the last months of the war. Maurois' Ni ange ni bete (Neither Angel, Nor Beast) is also set in Abbeville.

Christian Morel de Sarcus, in his novel Déluges, Éditions Henry, November 2004 (2005 Prix Renaissance), evokes the bombing of 1940 and the floods of the Somme of 2001.

Toponymy

[edit]The Romans occupied it and named it Abbatis Villa.[3][20]

The name of the city is attested in various forms over the centuries: Brittania (in the 3rd century), Abacivo villa (6th century), Bacivum palatium, Cloie and Cloye (in the 7th century), Abacivum villa, Basiu, Haymonis villa, Abbatis villa, Abbevilla (in the 11th century), Abbavilla,[21] Abedvilla, Abatis villa, Abbasvilla, Abbisvilla, Abbevile in 1209, Abbevilla in ponticio in 1213, Abisvil, Abeville in 1255, Abbeville in 1266, Abbisville, Abbeville en Pontiu (13th century), Albeville, Aubeville in 1358, Albeville in 1347, Aubbeville, Aubeville, Abevile (1383), Abbativilla and, finally, Abbeville, meaning the "Villa of the Abbé" because it once depended on the Abbey of Saint-Riquier.

There are also Hableville in 1607 and Ableville in 1643, with transitional addition of an L.

Abbekerke and Abbegem[22] in Flemish.

Heraldry

[edit]Abbeville boasted of having never been taken and was called Abbeville la pucelle ("the virgin"). It was also granted many privileges from the Capetian kings, to reward its loyalty.[23]

|

Charles V granted to Abbeville, by letters patent of 19 June 1369 dated to Vincennes, to focus on its coat of arms the leader of France and the motto: "Fidelis".[24]

The Abbeville arms are blazoned Azure three bendlets or, a bordure gules, a chief azure semé of fleurs-de-lis or.[25]

Decree of 2 June 1948: "Beautiful city, victim of the two World Wars, holder of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918, was the scene of violent fighting in 1940, during the Battle of the Somme. Suffered many bombardments from May 1940 to Liberation, which have caused the destruction of more than one-third of its houses and very painful human losses. Its severely affected population in its flesh and in possessions, did no less face the occupant businesses with a wonderful patriotism. Liberated on 2 September 1944, after severe fighting in streets, which was valiantly attended by its volunteer combatants inflicting severe losses on the enemy. In all circumstances proved worthy of a beautiful past of glory and loyalty to the motherland". (3 June 1948 Olympics) Citation to the order of the army of 12 August 1920: "By its military situation has been the object of repeated attacks by enemy aviation; despite its suffering and its mourning it has kept its patriotic faith intact." (14 August 1920 Olympics) Details: Charles V granted to Abbeville, by letters patent of 19 June 1369, Vincennes, to focus on its coat of arms the chief of France and the motto: "Fidelis". The Mayor's office of Abbeville uses this form, which voluntarily reverse the arms of Ponthieu. The mistake is often made. Even Robert Louis erred in "The Armorial of the Somme", which earned an added erratum. Since then, the error is taken from copy to copy. Jacques Dulphy.

|

Sobriquet

[edit]The blason populaire of the people of Abbeville is "chés bourgeois d'Adville".

Politics and administration

[edit]Abbeville was the capital of the former province of Ponthieu. Today, it is one of the three sub-prefectures of the Somme department.

Political trends and results

[edit]Presidential Elections Second Round:

| Election | Winning Candidate | Party | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Marine Le Pen | RN | 51.23 | |

| 2017[26] | Emmanuel Macron | EM | 55.64 | |

| 2012 | François Hollande | PS | 56.90 | |

| 2007 | Ségolène Royal | PS | 53.08 | |

| 2002 | Jacques Chirac | RPR | 82.62 | |

Intercommunality

[edit]The commune is part of the Communauté d'agglomération de la Baie de Somme of which it has the headquarters.

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]Palaeolithic

[edit]

The subsoil contains many vestiges of the Pleistocene. This discovery was a founding element of prehistory as a science.

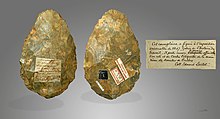

The name Abbeville has been adopted to name a category of paleolithic[3] stone tools. These stone tools are also known as handaxes. Various handaxes were found near Abbeville by Jacques Boucher de Perthes starting in 1838 and he was the first to describe the stones in detail, pointing out in the first publication of its kind, in 1846, that the stones were chipped deliberately by early man, so as to form a tool.[27] These stone tools which are some of the earliest found in Europe, were chipped on both sides so as to form a sharp edge, were known as Abbevillian handaxes or bifaces,[28] but recently the term 'Abbevillian' is becoming obsolete as the earlier form of stone tool, not found in Europe, is known as the Oldowan chopper. Some of these artifacts are displayed at the Musee Boucher-de-Perthes.[29]

A more refined and later version of handaxe production was found in the Abbeville/Somme River district. The more refined handaxe became known as the Acheulean industry, named after Saint-Acheul, today a suburb of Amiens.

It retained some importance into the Bronze Age.[3]

Antiquity

[edit]Although the research of Jacques Boucher de Perthes has highlighted an occupation of the site of Abbeville (Menchecourt-les-Abbeville quarter) from the Acheulean era, in Roman times it was a succession of marshes, similar to marsh of Saint-Gilles which remains today. Further to the north, the entire plateau between the Authie and the Somme was covered in primary forest. The Romans had to break through this forest massif for the passage of the road from Amiens to the village of Ponches on the one hand, and on the other to the west by the road linking the Beauvaisis in Boulogne-sur-Mer. The couple Abbeville / Saint-Valery-sur-Somme is the key to the historical enigma of the landing of Magnus Maximus and his Britto-Roman troops in the spring of 383 AD (St-Valery = Leuconos > Pors Liogan; Abbeville = Talence > Tolente). The road to Paris passes near the Vieux-Rouen-sur-Bresle, which has been identified with the character Himbaldus (Château-Hubault).[30]

Middle Ages

[edit]Early Middle Ages

[edit]In the 7th century, the Benedictine monks of Saint-Valéry, Saint-Josse, Saint-Saulve de Montreuil, Forest-Montiers, Balance and Valloires cleared the woods that were close to their monasteries. The Frankish king Dagobert I then gave part of the forest of Crécy, the hermitage became the Abbey of Saint-Riquier: it is the Act of birth of the abbatial field of Abbeville. The name, Abbeville, comes from the Latin and means "town (or more exactly) field of Abbots" (of Saint-Riquier).

The first historical mention of Abbeville, in the Chronicle of Hariulf,[note 1] dates to 831 AD. It was a small island in the Somme, inhabited by fishermen who took refuge there with their boats and had fortified it against barbarian invasions from the north. The Abbot Angilbert built a castle to defend this island, which depended on the Abbey of Saint-Riquier.[20][29] It was an important fort city responsible for the defense of the Somme.

In 992, Hugh Capet fortified the city and gave it to his daughter, Gisèle, on her marriage to Hugh I, Count of Ponthieu who resided in Montreuil.

High Middle Ages

[edit]

From the 12th century, the Abbot opened a leprosy hospice, the maladrerie des Frères du Val, moved to Grand-Laviers in the following century, before urban sprawl. Then accessible to boats, Abbeville became a port of the English Channel[note 2] under the dependence of the Abbots of Saint-Riquier. Subsequently, the silting up of the Bay of Somme forced the sea to recede by 12 kilometres (7.5 mi), but the city continued to be a trading port. Abbeville became the capital of the Ponthieu and rapidly spread on both banks of the River Somme, right on the slope of the hillsides and left into the marshes.

In 1095, Guy I Count of Ponthieu founded the Abbey Saint-Pierre of Abbeville and on 24 May 1098, he was dubbed as a Knight by Louis the Fat.

On the occasion of the First Crusade, Abbeville was the meeting point of many troops from the northern provinces. Godefroy de Bouillon reviewed them on the current location of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

With the rapid development of the salt trade (from Rue), woad (waide in Picard) and industry of wool cloth, the bourgeois increased in number and political importance: They asked for a charter granted in the course of the 12th century and which was confirmed in 1184[3][29] by Count John I of Ponthieu who died in Palestine. To commemorate the event, they built a belfry in 1126. A century later, Jeanne de Dammartin, Countess of Ponthieu (1220–1278), allowed the religious to convert an additional part of forests into cropland, allowing the development of the local economy. Afterwards it was governed by the Counts of Ponthieu. Together with that county, it came into the possession of the Alençon and other French families, and afterwards into that of the House of Castile.[31] In 1214, the Abbeville militia took part in the Battle of Bouvines.

In the middle of the 13th century, Abbeville was "one of the best cities of the Kings of France". Its port was one of the first of the Kingdom and its considerable trade.

In 1259, the Estates-General of the Kingdom stood at Abbeville and Henry III of England has met with Louis IX of France to sign the Treaty of Paris, which settled the question of the conquests of Philip Augustus.

In 1272, Ponthieu with Abbeville, passed by marriage to the kings of England, but Philip V took over the city, claiming that Edward II of England had not fulfilled its duty of vassal. Edward II complied with the feudal law, and Abbeville fell under English rule. However many challenges rose between the bourgeois and their new masters.

Late Middle Ages

[edit]Throughout the Hundred Years' War, the town was alternately occupied by English and French forces, causing the inhabitants of the town enormous suffering. They were tested by excessive taxes and terrible epidemics. Over the decades, the region was devastated by looting, epidemics and wolves. The city thus appealed to the King of France twice, in 1406 and in 1415.

Affected by the English expedition of 1346, Abbeville resisted the English army, and served as a home base for Jean Marant who refuelled Calais besieged by the English.

In 1360, it was transferred, with the County of Ponthieu of which it was the capital, to the Crown of England by the Treaty of Brétigny. That same year, John II of France stayed there after returning from captivity.

In 1361, Abbeville, again English, poorly welcomed its new masters. Ringois, a bourgeois of the city, refusing to take the oath of obedience to Edward III of England, was taken to English soil and hurled from the top of the Tower of Dover Castle into the sea in 1368.[32] During this period, a revolt of Jacques was defeated by the Abbeville militia in the vicinity of Saint-Riquier. The soldiers of Charles V captured the city by surprise, but the English recaptured it shortly after and it remained in their possession until 1385.

Like other Picardy cities, it then passed under Burgundian rule at the end of the Battle of Mons-en-Vimeu in 1421. In 1430, Henry VI of England was received at Abbeville.

In 1435, the city was ceded to Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, by the Treaty of Arras.[31]

Louis XI bought Abbeville from the Duke of Burgundy in 1463 and visited the city on 27 September of the same year. In December, by letters patent, he confirmed the privileges of the city, attached by his predecessors,[33] but in 1465 Charles the Bold revoked the grant by taking the lead of the League of the Public Weal.

In 1466, the municipality enacted safety regulations recommending to reduce or not use flammable materials (such as walls in timber or straw roofs) in construction, in order to reduce the risk of fire. However, it clashed with general hostility, and the regulations were finally just applied.[clarification needed][34]

Louis XI failed before Abbeville in 1471, but recovered Picardy on the death of the Duke of Burgundy in 1477.

Early modern era

[edit]In 1477 it was annexed by King Louis XI of France,[3] and was held by two illegitimate branches of the royal family in the 16th and 17th centuries, being in 1696 reunited to the crown.[31] In 1480, then 1483, a plague epidemic ravaged Abbeville. Charles VIII visited the town in 1493.

16th century

[edit]On 3 October 1514, Louis XII married Mary Tudor in Abbeville, the daughter of Henry VII of England.[20][29]

On 23 June 1517, Francis I came to Abbeville with the Queen and met Cardinal Wolsey, representing the King of England, to form a league against Charles V. In 1523, the English finally fell alongside Charles V in the wars of Francis I and the city had to suffer many frequent requisitions. That same year, an outbreak of plague ravaged Abbeville. A further epidemic of plague struck Abbeville in 1582.

In 1531, Francis I performed a new tour in the city. The most serious blows to Abbeville were the series of English raids by the Duke of Suffolk on the sides of the estuary in 1544, after the fall of Boulogne and Montreuil. King Henry II was received in Abbeville in 1550.

During the Wars of Religion, the Protestant governor was massacred with his family, by the people. In 1568, François Cocqueville, a Protestant leader of war, entered the Ponthieu with 3,000 soldiers.[35] He plundered and sacked the Abbey of Dommartin, towns, churches and castles of Authie and Saint-Valery-sur-Somme region.[35] Chased by the Marshal de Brissac, Cocqueville was captured with several of his own and they were beheaded in the marketplace of Abbeville.[36]

The St. Bartholomew's Day massacre caused no casualties in Abbeville due to the moderation of Léonor d'Orléans, the Duke of Longueville and governor of Picardy. However, Abbeville had embraced the Catholic League and suffered from the Wars of Religion, and it was relieved when it was recognised, by Henry IV in April 1594, despite the clergy who persisted in its resistance. Following this, on 18 December 1594, the King of France Henry IV visited Abbeville.

17th century

[edit]At the beginning of the 17th century a plague epidemic wreaked havoc. More than 8,000 people perished, thus depopulating Abbeville.

On 21 December 1620, King Louis XIII visited the town. His sister Henrietta went there several times.

In 1635 and 1636 the town suffered from the war against the Holy Roman Empire and Spain. They destroyed many villages located in the surrounding area. Richelieu stayed in the city in October. A plague epidemic raged again during the years 1635, 1636 and 1637.

In 1656, 6,000 soldiers, who had participated in the English Civil War, landed in France and took their quarters in Abbeville from where they left to go and reinforce the army of Turenne en route to Valenciennes. Shortly after, Balthazar de Fargues[note 3] sold the place to John of Austria and after meeting the price, he refused to deliver it to him, raising troops for himself who were then spread throughout the Ponthieu to ransom the inhabitants. Finally stopped, he was tried and hanged at Place Saint-Pierre on 17 March 1665.

In 1657, Louis XIV came twice to Abbeville with his mother, Anne of Austria.

By the mid-16th century, the woad trade shrank after the promotion of the pastel of the Pays du Midi, and it took to restructuring crafts. Colbert used it, and under Louis XIV, the city developed through the installation of Van Robais, manufacturers of sheets and tapestries from the Netherlands who, in 1665, created the Manufacture royale des Rames (drapery workshops).

In 1685, it suffered a serious blow at the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, the Protestant temple was destroyed and the persecuted workers who were the majority of skilled labour left the town, including those of Van Robais. The population decreased very strongly and never fully recovered from this exodus of talent.[3]

In 1693 the Ponthieu became the refuge of a considerable number of Bretons and Normans who had left their country because of famine, but they almost all perished of misery.

18th century

[edit]At the end of the reign of Louis XIV the country was covered with troops. The city crowded of sick and wounded. In 1708, after the capture of Lille, the troops of the Duke of Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy came forward frequently at the gates of Abbeville, ransoming the farms and villages. The winter of 1709 was terrible; people perished from cold, hunger and misery. At this time industry was quite dark and the State was required to help sheets manufacturers.

In 1717, Peter the Great passed through Abbeville.

In July 1766, the Chevalier de La Barre, accused of having, a year earlier, failed to give a due salute to a religious procession for Corpus Christi by refusing to remove his hat and singing ungodly songs. However, the story is more complex and revolves around a mutilated cross.[citation needed] He was executed on the Place du Grand-Marché for blasphemy. Subject to the issue, his legs were crushed. The right hand and the determined language, his decapitated corpse was finally delivered to the flames with the Dictionnaire philosophique of Voltaire on the same place. Today, a paving stone, engraved with his name and the date of his execution, is visible on the place of execution (Place Max-Lejeune), near the town hall. The martyrdom of the Chevalier de La Barre served as Voltaire's banner in his fight against religious fanaticism.[37]

On 2 November 1773, the powder magazine exploded killing 150 people and damaging nearly 1,000 houses.

Administratively, the people of Abbeville formed a subdelegation whose competence has been confused with that of the delegation of the same name (located in the Generalitat of Amiens). On the eve of the Revolution, Abbeville was the chef-lieu of a main electoral Bailiwick (without secondary Bailiwick).

Abbeville was fairly important in the 18th century, when the Van Robais Royal Manufacture (one of the first major factories in France) brought great prosperity (but some class controversy) to the town. Voltaire, among others, wrote about it.

Contemporary era

[edit]French Revolution

[edit]There were no significant excesses during periods of Revolution and the Terror.

In 1793, on Place Saint-Pierre the furniture of the churches was burned, along with images and the feudal titles. The Church of Saint-vulfran became the Temple of Reason.

On 8 June 1794, a festival was celebrated in honour of the Supreme Being. Abbeville suffered from famine in 1794 and 1795.

On 5 January 1795, the Hotel of Grutuze, built under Charles VII, attended by the directors of the district, was destroyed by a fire.

In 1797, the Society of Emulation of Abbeville, one of the oldest learned societies of France, was created.

In 1798 and 1799, the winter was severe and a part of the town[38] was flooded.

Consulate and Empire

[edit]On 18 brumaire year X (9 November 1801), there was a terrible hurricane that caused more than 1,300,000 francs worth of damage in the arrondissement.

On 29 prairial year XI (18 June 1803), Napoleon passed through the town for the first time. During the preparations of the expedition he was planning against the United Kingdom, the First Consul often spent time in Abbeville by going to the camp of Boulogne.

In 1813, as part of the reorganisation of the cavalry which had been decimated in Russia, the arrondissement offered the government 43 men mounted and equipped.

Early in 1814, with invasion becoming more imminent every day, the urban National Guard was reorganised across the whole of the Empire. 30 pieces of artillery were placed on the walls, and to complete the defense system, trees were felled in the vicinity to make 30,000 palisades and 14,000 shields. On 20 February, a column of cavalry forming the vanguard of the 3rd Corps of the Prussian army, commanded by Baron de Geismar, arrived in Doullens, before heading to Abbeville. Immediately, the Abbevillois ran to arms. 800 rifles were made available and a vigorous resistance began when the population learned that this supposed vanguard of the Prussian army had more than 1,500 to 2,000 men in its ranks, both Cossacks and Saxon Lancers, who eventually made their way to Paris.

In early April, after the Battle of Paris and the abdication of Napoleon, 2,000 Lancers and Prussian cuirassiers commanded by General Röder arrived from Paris and the surrounding countryside, and committed all kinds of excesses during their stay.

On 27 April 1814, Louis XVIII entered the town and was received with an outpouring of joy. He stayed at the Abbey of Saint-Pierre.

During the First Restoration, many distinguished people and about 10,000 British troops passed through Abbeville, to return to their country. The Duke of Berry, accompanied by the 10th Regiment of Cuirassiers and the 108th Infantry Regiment, stayed there.

On 21 March 1815, King Louis XVIII, who was on the way to exile, spent a night in the town.

In 1815, after the Battle of Waterloo, the town was again put into defence. However, after numerous desertions, the garrison was reduced to 400 men.

July monarchy, Second Republic and Second Empire

[edit]

Victor Hugo came to Abbeville three times, as a tourist: In 1835, he stayed there successively from July 26 (after going down to L'Écu de Brabant), then on 4 and 5 August (staying at L'Hôtel d'Angleterre). In August and September 1837, he came to Amiens after having descended the Somme by Steamboat. Finally, in 1849, leaving the city in the rain on 11 September.

In 1847, there was the arrival of the railway in Abbeville with the opening of the Amiens-Abbeville section of the line of the Longueau–Boulogne railway. In 1856, the Abbeville railway station was inaugurated, which is still in service.

End of 19th century and Belle Epoque

[edit]Abbeville was the birthplace of Rear Admiral Amédée Courbet (1827–1885), whose victories on land and at sea made him a national hero during the Sino-French War (August 1884 to April 1885). Courbet died in June 1885, shortly after the end of the war, at Makung in the Pescadores Islands, and his body was brought back to France and buried in Abbeville on 1 September 1885 after a state funeral at Les Invalides a few days earlier. Abbeville's old Haymarket Square (Place du Marché-au-Blé) was renamed Place de l'Amiral Courbet in July 1885, shortly after the news of Courbet's death reached France, and an extravagant baroque statue of Courbet was erected in the middle of the square at the end of the nineteenth century. The statue was damaged in a devastating German bombing raid during World War II.[citation needed] It was an allied base during World War I.[20]

In 1896, the Socialist Jules Guesde came to lecture in Abbeville. In the aftermath, a group of the French Workers' Party and a House of the people are created. 1899, the phone has already arrived in Abbeville but its operation does not any satisfaction.

In 1899, Abbeville industry had a mill, a table linen factory, a rope factory, a factory of weight scales, three smelters, a boiler works, a locksmith for buildings, a wood grinding mill, a distillery, etc.

On 7 July 1907 was the inauguration of the La Barre Monument, gathering many Republicans, delegates from Socialist groups and free-thinkers.

World War I and the conferences of Abbeville

[edit]During World War I, the town was never occupied by the German troops (as evidenced by the monument built on the Mont de Caubert).

In 1916, during the Battle of the Somme, it served as a military hospital (the 3rd Australian General Hospital). As with Amiens and Beauvais, the town was partially destroyed and the aftermath of war is significant nearby, particularly due to unexploded ordnance still found in the soil.

In 1918, it was the seat of two Anglo-French conferences (conferences of Abbeville): That of 25 March, between Field Marshal Haig and Generals Wilson and Foch, who convened the Doullens conference. During the second conference on 2 May, Foch demanded authority on the Italian front but only obtained a power of coordination. It was at the Conference of Abbeville (1 and 2 May 1918) while the armies weakened that Foch opposite Clemenceau and Lloyd George would have considered a fallback to the south to protect the capital. In the event that the French and British armies were separated and they could no longer defend both access to the ports of the English Channel and Paris, the British army would have then withdrawn and stood on the Somme.

On May 31, 1918, American war poet John Allan Wyeth was a Second Lieutenant in the 33rd U.S. Infantry Division, which was largely composed of soldiers from the Illinois Army National Guard. Lt. Wyeth and his fellow Doughboys were stationed in nearby Huppy, when German aeroplanes began a bombing raid on Abbeville. At the time, such air raids were a nightly affair and Abbeville was in the process of being evacuated. Lt. Wyeth later versified his memories of the air raid in the sonnet Huppy.[39]

Interwar period

[edit]On 3 May 1936, voters in the 1st District of Abbeville did not derogate from a broad popular movement. In the 2nd round, they chose Max Lejeune as the MP who, at 27 years old, was the youngest elected to the chamber.

World War II

[edit]

On 12 September 1939 a conference in Abbeville took place in which France and the United Kingdom decided to not continue the attack on Germany, which resulted in a tougher situation on eastern front. On 9 May 1940, authorities in Belgium arrested a number of both far right and far left activists and put them in custody of a French Army unit stationed near Abbeville. On 20 May, when the advancing German Army cut off the area (see following), a group of French soldiers carried out a massacre and killed a number of members of the right wing Verdinaso and Rexist Party and of the Belgian Communist Party. Altogether, twenty two suspects of varying political stripe were selected and executed without trial.

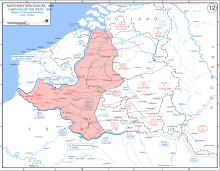

In the development of the 1940 Battle of France, the Germans had massed the bulk of their armoured force in Panzer Group von Kleist, which attacked through the comparatively unguarded sector of the Ardennes and achieved a breakthrough at Sedan with air support. The group raced to the coast of the English Channel at Abbeville, thus isolating (20 May 1940)[3] the British Expeditionary Force, Belgian Army, and some divisions of the French Army in northern France.[citation needed]

Charles de Gaulle (17–18 May 1940), then a colonel, launched a counterattack in the region of Laon (see the map) with 80 tanks to destroy the communication of the German armoured troops. His newly formed 4e Division cuirassée reached Montcornet, resulting in the Battle of Montcornet. Without support, the 4th DCR was forced to retreat. The Abbeville massacre took place on 20 May 1940. Abbeville was taken by the Germans from the 2nd Panzer Division of Generalmajor Rudolf Veiel, also on 20 May 1940. There was another counter-attack with the Battle of Abbeville. After Laon (24 May), de Gaulle was promoted to temporary general: "On 28 May (...) the 4th DCR attacked twice to destroy a pocket captured by the enemy south of the Somme near Abbeville. The operation was successful, with over 400 prisoners taken and the entire pocket mopped up except for Abbeville (...) but in the second attack the 4th DCR failed to gain control of the city in the face of superior enemy numbers."[40] The Germans were forced back about 50 kilometres (31 mi). The Allied Aerodrome Abbeville was used by the German Luftwaffe during most of the war.

After five years, in September 1944, Abbeville was liberated by the Polish 1st Armoured Division (which was attached to the 1st Canadian Army) under General Stanisław Maczek, which entered Abbeville through the suburb of Rouvroy. World War II was not kind to the architecture of the town as the famous 17th-century Gothic Cathedral of St. Vulfran was nearly destroyed.[3] It, along with the town hall with its tower from the 13th century were saved, albeit damaged.[29]

Floods of 2001

[edit]In the spring of 2001, the city, like the Somme Valley, had to suffer floods. These lasted several weeks, because of the saturation of the water table, the result of a year of exceptional precipitation. The station was inaccessible, the tracks being covered by several centimetres of water.

Military life

[edit]Units which have been stationed in Abbeville:

Places and monuments

[edit]The city was very picturesque until the early days of the Second World War when it was bombed mostly to rubble in one night by the Germans. The town overall is now mostly modern and rebuilt.

Collegiate Church of Saint-Vulfran

[edit]

The Collegiate Church of Saint-Vulfran (Wulfram of Sens) was constructed from 1488 and into the 16th and 17th centuries, although the original design was not completed. The nave has only two bays and the choir is insignificant. However, the façade is a masterpiece of flamboyant Gothic architecture, which made the city famous, and is flanked by two Gothic towers.[31] Wulfram, its patron saint who is celebrated on 20 March, was born c. 650 AD, in Milly (Gâtinais), and was Lord at the Court of Chlothar III, Abbot of Fontenelle, Archbishop of Sens in 682, and an evangeliser of Frisia. He died at Saint-Wandrille (Fontenelle Abbey) in 720. The building was classified as a historical monument in 1840.[41]

Theatre

[edit]Built in 1911, the theatre is one of the few in the region that boasts an Italian room. Registered as an historical monument in 2003.

Belfry

[edit]

Classified as a World Heritage Site in 2005 and registered as an historic monument in 1926, the belfry is one of the oldest in France, built in 1209. On 20 May 1940, during a bombing, its roof was damaged and it was only in 1986 that it was rebuilt. The belfry is one of the fifty-six belfries of Belgium and France registered in 2005 by the World Heritage Committee of UNESCO in recognition of its testimony to the rise of municipal power in the region and its architecture.[42] It has housed the museum of the city since 1954.

Boucher de Perthes Museum

[edit]

The Boucher de Perthes Museum is partly situated in the now unused bell tower of the 13th century which is inscribed on the World Heritage list.[42] It is a tribute to Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes who also has a lycée named after him. The museum features artwork and artifacts from the 16th century onwards, along with other exhibitions that periodically change.

Château de Bagatelle

[edit]- Southeast of the town is the Château de Bagatelle from the 18th century.[15] The folly was built in 1752 by Josse Van Robais. Inscribed as an historical monument in 1926, the regular garden and park were registered as historic monuments in 1946.

Manufacture des Rames

[edit]Classified as an historic monument in 1986,[43] the Manufacture des Rames specialised in the production of luxury linen. The building was partly constructed in 1710.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

[edit]The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, situated in the heart of the old town centre, is a collegiate Gothic church from the 11th century. The thirty-one stained glass windows were designed by Alfred Manessier (1911–1993) and were made in Chartres. The church was classified as an historical monument in 1907.[44]

Other churches

[edit]- Church of our Lady of the Chapel: Steeple classified as an historical monument in 1910,[45] the 18th century pulpit classified as an historical monument in 1909.[46] Many objects inscribed as historical monuments in 1981, statues: Christ on the cross (15th century), God of mercy (16th century), Saint Nicolas (17th century), saint holding a sceptre (18th century), two bishops forming counterparts (Simon Pfaff de Pfaffenhoffen, 18th century), Sainte Genevieve and Saint Louis (19th century); two stools of the church (17th century); buffet of organs (18th century); tableaus: the Holy Family (17th century), the Virgin (19th century), funerary stele (19th century).

- The Church of Saint-Gilles registered as an historical monument in 1926.

- The Priory of Saint-Pierre and Saint-Paul of Abbeville inscribed as an historical monument in 1993 (façades and roofs).

- Church of Saint-Silvin de Mautort.

- The Church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Rouvroy, built in brick, and has a bell tower with an offset clock.

- The Church of Saint-Jacques, which was built in the Gothic Revival style by architect Victor Delefortrie. Poorly maintained, the municipal council voted on 7 February 2013 for its demolition, despite a certain wave of protest.[47] The demolition was completed in May of the same year.

Archaeological sites

[edit]- The Carpentier excavation: An archaeological site of the Lower Paleolithic, classified as an historical monument in 1983.[48]

- The Menchecourt excavation: An archaeological site of the Lower Paleolithic, classified as an historical monument in 1983.[49]

La Barre Monument

[edit]The La Barre Monument was erected in 1907 by public subscription, in commemoration of the martyrdom of the Chevalier de La Barre. Located near the station, next to the bridge on the Somme canal, the La Barre Monument is an annual rallying point, on the first Sunday of July, for defenders of secularism and freethinkers.

Other memorials

[edit]

- War memorial of the war of 1870, due to an Alsatian, Xavier Niessen, founder of the Souvenir français.[50]

- Monument to Admiral Courbet, the work of Alexandre Falguière and Antonin Mercié.

- War memorial of the Great War, Les Patrouilleurs sculpture due to Louis-Henri Leclabart. Made of stone from Lavoux, the sculpture depicts a scene from the trenches. The monument was unveiled in 1923 by Marshal Foch.

Parks and public gardens

[edit]

- The garden of Emonville in which is situated the Robert Mallet municipal library and the service of the municipal archives is named after one of its owners Arthur Foulques d'Emonville, an amateur botanist who had bought a part of the Priory of Saint-Pierre and Saint-Paul of Abbeville, to accommodate a garden, and to construct a mansion. The main entrance to the garden is a remnant of the priory.

- The Carmel and its gardens

- The municipal park of the Bouvaque is home to many sedentary and migratory birds as well as willow, reed beds, etc.

Other monuments

[edit]

- The Hotel Rambures, of the 18th century, inscribed as an historic monument in 1977.

- The Hotel Buigny inscribed as an historic monument in 1933.

- Abbeville railway station, of "seaside regional" style, is built around a frame of wood with red brick cladding, inscribed as an historical monument in 1984.

- The bathhouse of Abbeville, built in 1909–1910 by Caisse d'Épargne on the plans of the architects Greux and Marchand. The sculptures are of Louis-Henri Leclabart (1876–1929), creator of the war memorial of Abbeville and the Delique Stadium. Registered as an historical monument in 2003.

- In the town centre, a dozen old houses dating from the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries were classified as historical monuments or registered as historical monuments between 1924 and 1974.

- The town hall, inaugurated in 1960.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Abbeville is twinned with:

Argos, Greece (1993)[51]

Argos, Greece (1993)[51] Burgess Hill, England, United Kingdom (1994)[52]

Burgess Hill, England, United Kingdom (1994)[52]

Notable people

[edit]- St Vulflagius (died c. 643), also known as 'St Vulphy' or 'St. Wulflagius', hermit priest greatly venerated in Montreuil-sur-Mer.[53]

- Roger Agache (1926–2011), archaeologist, considered one of the pioneers of aerial archaeology

- François-Germain and Jacques Aliamet (1726–1788), engravers

- Jacques Firmin Beauvarlet (1731–1797), writer

- Jean-Jacques Beauvarlet-Charpentier (1734–1794), harpsichordist, organist and composer

- Gabriel Barbou des Courières (1761–1827), general of the Revolution and the Empire

- Rose Bertin (1737–1813), milliner and dressmaker to Queen Marie Antoinette

- Georges Bilhaut (1882–1963), painter

- Jacques Boucher de Perthes (1788–1868), one of the founders of the study of prehistory. As a tribute, the museum and the public school bear his name.

- Philippus Brietius (1601–1668), Jesuit and scholar

- Alfred Broquelet (1861–1957), painter and lithographer

- Jacques Buteux (1600–1652), born in Abbeville, New France Jesuit in Trois-Rivières

- Abbé Pierre Carpentier (1912–1943), priest and resistance figure, deported and beheaded at Dortmund. He was vicar of the parish of Saint Gilles of Abbeville and had much invested in local Scouting. The Scouts et Guides de France of Abbeville Group bears his name.

- Louis Cordier (1777–1861), engineer of the Corps des mines, geologist and mineralogist

- Père Antoine Désiré Mégret (born 1797) Capuchin missionary, founded Abbeville, Louisiana

- Robert Cordier, engraver, active 1629–1653

- Admiral Anatole-Amédée-Prosper Courbet (1827–1885), French admiral; a commemorative monument is located in the square bearing his name

- Jacques Darras (born 1939), academic and poet

- Mickaël Debève (born 1970), footballer

- Louis-Alexandre Dévérité (1743–1818), Deputy of the Somme during the French Revolution

- Didier Drogba (born 1978), Franco-Ivorian footballer, lived in Abbeville during his childhood. He was also a player for SC Abbeville.[54]

- Gaston Dufresne (1886–1963), figure of the Resistance (member of Réseau Zéro France), President of the HLM office (1928–1963), Vice President of the Board of Directors of the National Federation of HLM cooperative societies, Councillor (1945–1953) and Deputy Mayor (1953–1963). In May 1965, on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of cooperative housing society co-founded by Gaston Dufresne (he has launched the construction of housing in accession to the property and contributed to the establishment of 500 of these homes in Abbeville), Max Lejeune, Mayor of Abbeville, inaugurated the street which bears the name of this tireless activist: "we wanted his name to remain forever engraved in our city" to keep the memory of "a hard worker hard who always fulfils his task voluntarily".[55]

- Johann Duhaupas (born 1981), boxer

- André Dumont (1764–1838), several times member of Parliament for the sum under the Revolution, was sub-prefect of Abbeville during the First Empire

- Pierre Duval (1618–1683), geographer

- Emmanuel Fontaine (1856–1935), sculptor

- Thomas Gaugain (1756–1812), painter and engraver

- Pierre-François-Pascal Guerlain (1798–1864), founder of the Guerlain perfume empire

- Philippe Hecquet (1661–1737), physician

- Nicolas Jean Hugon de Bassville (1743–1793), hero and martyr sans-culotte

- François-Jean de la Barre (1745–1766), victim of religious intolerance; a Monument La Barre commemorates him

- Edmond de La Fosse (1481–1503), Calvinist schoolboy (regarded as a heretic) executed in the Butte Saint-Roch in Paris, for having desecrated the sacramental bread

- Max Lejeune (1909–1995), mayor from 1947 to 1988, MP, Minister, Senator

- Adolphe Leroy (1810–1888), artist, illustrator and lithographer

- Alfred Le Roy de Méricourt (1825–1901), physician, Member of the Academy of Medicine

- Jules Gabriel Levasseur (1823 – after 1878), engraver

- Pierre-François Levasseur (1753 – after 1815), cellist

- François César Louandre and Charles Léopold Louandre (1812–1882), historians

- Louis XII married in Abbeville in 1514

- Stanisław Maczek (1892–1994), Polish general commanding the 1st Armoured Division having released Abbeville in September 1944, made honorary citizen of the city.

- Robert Mallet, writer

- Alfred Manessier (1911–1993), representational painter, creator of the stained glass windows of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

- Jean Marant, marine and privateer from the 14th century, who became famous during the Hundred Years' War

- Jacques Marseille (1945–2010), historian, specialist of economic history

- Claude Mellan (1598–1688), painter

- Jean Miélot († 1472), private secretary to the Dukes of Burgundy

- Charles Hubert Millevoye (1782–1816), poet

- Gabriel Naudé, organiser of the Bibliothèque Mazarine, died in 1653 in Abbeville

- Henri Padé (1863–1953), mathematician

- François de Poilly (1623–1693), engraver

- Aimé Louis Richardot, Mayor of Reims (from 1849 to 1850), died in 1884 at Abbeville

- Jean-Baptiste Sanson de Pongerville (1782–1870), politician and academician

- Nicolas Sanson, cartographer, advisor to Louis XIII

- Éric Yung (born 1948), policeman and journalist

- Jérémy Stravius (born 1988), swimmer

- Najat Vallaud-Belkacem (born 1977), politician

- Evens Stievenart (born 1983), racing driver

See also

[edit]- Bay of Somme

- Battle of Abbeville

- Beffroi d'Abbeville

- Ponthieu

- Église Saint-Silvin de Mautort

- Église Saint-Vulfran d'Abbeville

- Église Saint-Sépulcre d'Abbeville

- List of churches with an eccentric clock tower

- Forêt de Crécy

- History of Abbeville

- Travel of Victor Hugo

- Ponthieu

- List of Comtes de Ponthieu

- Communes of the Somme department

- Rural exodus in Somme

- List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in the Somme

Bibliography

[edit]- Hugo, Victor (1987). Œuvres Complètes – Voyages [Complete Works – Travel]. Bouquins (in French). Paris: Éditions Robert Laffont.

- Lesueur, Charles. Abbeville pendant la Guerre de 1914–1918 [Abbeville during the War of 1914–1918] (in French).

- Louandre, François-César. Recherches sur la topographie du Ponthieu, avant le siecle XIVe [Research on the topography of Ponthieu, before the fourteenth century] (in French).

- Louandre, François-César (1829). Biographie d'Abbeville et de ses environs [Biography of Abbeville and its surroundings] (in French). Devérité.

- Louandre, François-César (1834). Histoire ancienne et moderne d'Abbeville et de son arrondissement [Ancient and modern history of Abbeville and its arrondissement] (in French). A. Boulanger.

- Louandre, François-César (1837). Lettres et bulletins des armées de Louis XI, adressés aux officiers municipaux d'Abbeville [Letters and newsletters of the armies of Louis XI, addressed to municipal officers of Abbeville] (in French). with explanations and notes.

- Maisse, Gérald (2005). Paillart, F. (ed.). Occupation et Résistance dans la Somme 1940–1944 [Occupation and Resistance in the Somme 1940–1944] (in French). Abbeville. ISBN 978-2-85314-019-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mallet, Robert. Les Riches heures d'Abbeville [The Rich hours of Abbeville] (in French).

- Mallet, Robert. Mes souvenirs sur la vie abbevilloise [My memories of the Abbeville life] (in French).

- Micberth, Michel-Georges; Louandre, François César (1998) [1883]. Histoire d'Abbeville et du comté de Ponthieu jusqu'en 1789 [History Abbeville and Ponthieu County until 1789]. Monographies des villes et villages de France (in French).

- Louandre, François-César (1998). Vol. I (in French). Vol. I. Le Livre d'Histoire. ISBN 978-2-84435-013-8.

- Louandre, François-César (1998). Vol. II (in French). Vol. II. Le Livre d'Histoire. ISBN 978-2-84435-014-5.

- Morel de Sarcus, Christian (2004). Déluges [Floods] (in French). Éditions Henry. (memory of the bombing of 1940 and the floods of the Somme in 2001).

- Prarond, Ernest (1850). Notice sur les rues d'Abbeville [Instructions on the streets of Abbeville] (in French).

- Prarond, Ernest (1854). Notices historiques, topographiques et archéologiques sur l'arrondissement d'Abbeville [Historical, topographical and archaeological records of the arrondissement of Abbeville] (in French).

- Prarond, Ernest (1875). Abbeville à table, études gourmandes et morales [Abbeville to table, gourmet and ethical studies] (in French).

- Prarond, Ernest (1871). La Topographie historique et archéologique d'Abbeville [The historical and archaeological topography of Abbeville] (in French).

- Prarond, Ernest (1873). La Ligue à Abbeville, 1576–1594 [The League in Abbeville, 1576–1594] (in French). Paris Dumoulin.

- Prarond, Ernest (1886). Les Convivialités de l'échevinage, ou l'Histoire à table [The convivialities of the aldermen, or table history] (in French).

- de Wailly, Henri (1980). Le Coup de faux: l'assassinat d'une ville (Abbeville 1940) [The false strike: The assassination of a city (Abbeville 1940)] (in French). Copernic.

- de Wailly, Henri (1990). De Gaulle sous le casque, Abbeville 1940 [De Gaulle under the helmet, Abbeville 1940] (in French). Librairie académique Perrin.

- de Wailly, Henri (1995). La Victoire évaporée: Abbeville 1940 [The Evaporated Victory: Abbeville 1940] (in French). Librairie académique Perrin.

- de Wailly, Henri (2012). L'Offensive blindée d'Abbeville 27 mai – 4 juin 1940 [The Abbeville Armored Offensive 27 May 27 to 4 June 1940] (in French). Economica.

- Online

- Anon (2015). "British Towns Twinned With French Towns". Complete France. Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Anon (2014). "The "Phoney War" (1940)". Charles-de-gaulle.org. Foundation Charles De Gaulle. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Anon (2007). "Le CM2 a Visité la sucrerie" [The CM2 Visited the Sugar Refinery] (in French). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- Encyclopaediae

- Asimov, Isaac (1964). "Boucher De Crèvecœur de Perthes". Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology: The Living Stpries of More than 1000 Great Scientists from the Age of Greece to the Space Age. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc. LCCN 64016199.

- Canby, Courtlandt (1984). "Abbeville". Encyclopedia of Historic Places. Vol. I: A-L. New York, NY: Facts on File Publications. ISBN 0-87196-397-3. LCCN 80025121.

- Cohen, Saul B., ed. (1998). "Abbeville". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World. Vol. 1: A to G. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5. LCCN 98071262.

- Darvill, Timothy, ed. (2008). "Abbeville, France". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953404-3. LCCN 2008279152.

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abbeville". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8. LCCN 2008934270.

- Van Valkenburg, Samuel (1997). "Abbeville". In Johnston, Bernard (ed.). Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. I: A to Ameland (1st ed.). New York, NY: P. F. Collier. LCCN 96084127.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also written as Hariulphe

- ^ In fact, sea vessels docked instead at that time in Grand-Laviers, but the goods can be brought by large boats into the heart of the city, as evidenced by the suburb "du Guindal".

- ^ Balthazar de Méalet de Fargues, seigneur of Cincehours, Captain-major of the regiment of Bellebrune

References

[edit]- ^ "Répertoire national des élus: les maires" (in French). data.gouv.fr, Plateforme ouverte des données publiques françaises. 13 September 2022.

- ^ "Populations légales 2021" (in French). The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies. 28 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Van Valkenburg 1997, p. 8

- ^ "Chapelle St Pierre St Paul". association du prieuré.

- ^ Lefebvre, F.A. (1885). La chartreuse de Saint-Honoré à Thuison près d'Abbeville. Bray et Retaux. p. 25. 571.

- ^ Lefebvre, 1885, p.381

- ^ Lefebvre, 1885, p.383

- ^ "Données climatiques de la station de Abbeville" (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Climat Picardie" (in French). Meteo France. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Normes et records 1961–1990: Abbeville (80) – altitude 70m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui: Commune data sheet Abbeville, EHESS (in French).

- ^ Population en historique depuis 1968, INSEE

- ^ "Évolution et structure de la population en 2017, Commune d'Abbeville (80001)". INSEE. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Évolution et structure de la population en 2017, Département de la Somme (80)". INSEE. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d Cohen 1998, p. 3

- ^ Anon 2007

- ^ "Bibliothèque municipale (section "étude et patrimoine") d'Abbeville". CR2L de Picardie. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Les Nuits du Blues (présentation du programme 2011)". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Le palmarès des villes et villages fleuris". Le Courrier Picard, Oise Edition. 5 July 2008.

- ^ a b c d Canby 1984, p. 2

- ^ Hippolyte Cocheris, Conservateur de la Bibliothèque Mazarine, Conseiller général du département de Seine-et-Oise, DICTIONNAIRE DES ANCIENS NOMS DES COMMUNES DU DÉPARTEMENT DE SEINE-ET-OISE, 1874

- ^ "Origine des noms flamands". Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "Historique d'Abbeville". ot-abbeville.fr.

- ^ Estienne, Jacques; Louis, Mireille (1972). Armorial du Département et des Communes de la Somme. Abbeville: F. Paillart.

- ^ "Abbeville, Porte de la Baie de Somme – un peu d'histoire" (in French). Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "Résultats élections: Abbeville". Le Monde.

- ^ Asimov 1964, p. 223

- ^ Darvill 2008, p. 1

- ^ a b c d e Hoiberg 2010, p. 11

- ^ See bibliography and external links

- ^ a b c d One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abbeville". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 11.

- ^ L'héroïsme de Ringois nous est connu par un passage des Grandes chroniques de France (Règne de Charles V. p. 97)

- ^ Lettres patentes de Louis XI. Crotoy. December 1463. p. 154.

- ^ Leguay, Jean-Pierre (2005). Les catastrophes au Moyen Âge. Les classiques Gisserot de l'histoire. Paris: J.-P. Gisserot. p. 186. ISBN 2-87747-792-4.

- ^ a b Poullain de Saint-Foix, Germain-François (1766). Histoire de l'Ordre du Saint-Esprit. Vol. 1. Paris: Vve Duchesne. pp. 45–46.

- ^ Louandre, F.-C. Hist. ancienne et moderne d'Abbeville. p. 303.

- ^ See in particular the article "Torture" that he added in his Dictionnaire philosophique following the event.

- ^ Saint-Jacques quarter, chaussée d'Hocquet, suburbs of Planches and de Rouvroy

- ^ John Allan Wyeth (2008), This Man's Army: A War in Fifty-Odd Sonnets, pages xxxii, 12.

- ^ Anon 2014

- ^ Base Mérimée: Eglise Saint-Vulfran ou ancienne collégiale, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ a b "Belfries of Belgium and France". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Base Mérimée: Ancienne manufacture des Rames, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Base Mérimée: Eglise du Saint-Sépulcre, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Base Mérimée: Eglise Notre-Dame-de-la-Chapelle, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Base Palissy: Chaire à prêcher, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ "L'église Saint-Jacques d'Abbeville va être détruite". La Tribune de l'art. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ Base Mérimée: Carrière Carpentier, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Base Mérimée: Carrière de Menchecourt, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ "Abbeville". Archived from the original on 30 September 2012. and "Abbeville – Monument aux morts 1939/1945". Archived from the original on 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Argos en Grèce". abbeville.fr (in French). Abbeville. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Burgess Hill en Grande-Bretagne". abbeville.fr (in French). Abbeville. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "Saint Vulflagius of Abbeville". 3 June 2009.

- ^ Dubois, Claude (1990). "DROGBA AU SCA". abbsport.com.

- ^ Le Courrier picard, 23 May 1965

External links

[edit] Media related to Abbeville at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abbeville at Wikimedia Commons Abbeville travel guide from Wikivoyage

Abbeville travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official website (in French)