Pyloric stenosis

| Pyloric Stenosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Outline of stomach, showing its anatomical landmarks, including the pylorus. | |

| Specialty | General surgery |

| Symptoms | Projectile vomiting after feeding[1] |

| Complications | Dehydration, electrolyte problems[1] |

| Usual onset | 2 to 12 weeks old[1] |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Risk factors | Cesarean section, preterm birth, bottle feeding, first born[3] |

| Diagnostic method | physical examination,[1] ultrasound[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Gastroesophageal reflux,[1] intussusception[5] |

| Treatment | Surgery[1] |

| Prognosis | Excellent[1] |

| Frequency | 1.5 per 1,000 babies[1] |

Pyloric stenosis is a narrowing of the opening from the stomach to the first part of the small intestine (the pylorus).[1] Symptoms include projectile vomiting without the presence of bile.[1] This most often occurs after the baby is fed.[1] The typical age that symptoms become obvious is two to twelve weeks old.[1]

The cause of pyloric stenosis is unclear.[2] Risk factors in babies include birth by cesarean section, preterm birth, bottle feeding, and being firstborn.[3] The diagnosis may be made by feeling an olive-shaped mass in the baby's abdomen.[1] This is often confirmed with ultrasound.[4]

Treatment initially begins by correcting dehydration and electrolyte problems.[1] This is then typically followed by surgery, although some treat the condition without surgery by using atropine.[1] Results are generally good in both the short term and the long term.[1]

About one to two per 1,000 babies are affected, and males are affected about four times more often than females.[1] The condition is very rare in adults.[6] The first description of pyloric stenosis was in 1888, with surgical management first carried out in 1912 by Conrad Ramstedt.[1][2] Before surgical treatment, most babies with pyloric stenosis died.[1]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Babies with this condition usually present any time in the first weeks to 6 months of life with progressively worsening vomiting. It is more likely to affect the first-born with males more commonly than females at a ratio of 4 to 1.[7] The vomiting is often described as non-bile stained ("non bilious") and "projectile vomiting", because it is more forceful than the usual spitting up (gastroesophageal reflux) seen at this age. Some infants present with poor feeding and weight loss but others demonstrate normal weight gain. Dehydration may occur which causes a baby to cry without having tears and to produce less wet or dirty diapers due to not urinating for hours or for a few days. Symptoms usually begin between 3 and 12 weeks of age. Findings include epigastric fullness with visible peristalsis in the upper abdomen from the infant's left to right.[8] Constant hunger, belching, and colic are other possible signs that the baby is unable to eat properly.

Causes

[edit]Rarely, infantile pyloric stenosis can occur as an autosomal dominant condition.[9] It is uncertain whether it is a congenital anatomic narrowing or a functional hypertrophy of the pyloric sphincter muscle.[citation needed]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The gastric outlet obstruction due to the hypertrophic pylorus impairs emptying of gastric contents into the duodenum. As a consequence, all ingested food and gastric secretions can only exit via vomiting, which can be of a projectile nature. While the exact cause of the hypertrophy remains unknown, one study suggested that neonatal hyperacidity may be involved in the pathogenesis.[10] This physiological explanation for the development of clinical pyloric stenosis at around 4 weeks and its spontaneous long term cure without surgery if treated conservatively, has recently been further reviewed.[11]

Persistent vomiting results in loss of stomach acid (hydrochloric acid). The vomited material does not contain bile because the pyloric obstruction prevents entry of duodenal contents (containing bile) into the stomach. The chloride loss results in a low blood chloride level which impairs the kidney's ability to excrete bicarbonate. This is the factor that prevents correction of the alkalosis leading to metabolic alkalosis.[12]

A secondary hyperaldosteronism develops due to the decreased blood volume. The high aldosterone levels causes the kidneys to avidly retain Na+ (to correct the intravascular volume depletion), and excrete increased amounts of K+ into the urine (resulting in a low blood level of potassium).[citation needed]The body's compensatory response to the metabolic alkalosis is hypoventilation resulting in an elevated arterial pCO2.

Diagnosis

[edit]

Diagnosis is via a careful history and physical examination, often supplemented by radiographic imaging studies. Pyloric stenosis should be suspected in any infant with severe vomiting. On physical exam, palpation of the abdomen may reveal a mass in the epigastrium. This mass, which consists of the enlarged pylorus, is referred to as the 'olive',[14] and is sometimes evident after the infant is given formula to drink. Rarely, there are peristaltic waves that may be felt or seen (video on NEJM) due to the stomach trying to force its contents past the narrowed pyloric outlet.[citation needed]

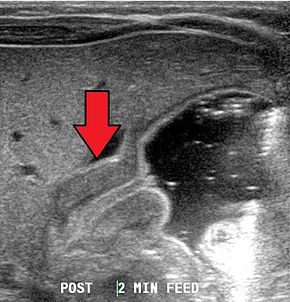

Most cases of pyloric stenosis are diagnosed/confirmed with ultrasound, if available, showing the thickened pylorus and non-passage of gastric contents into the proximal duodenum. Muscle wall thickness 3 millimeters (mm) or greater and pyloric channel length of 15 mm or greater are considered abnormal in infants younger than 30 days. Gastric contents should not be seen passing through the pylorus because if it does, pyloric stenosis should be excluded and other differential diagnoses such as pylorospasm should be considered. The positions of superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein should be noted because altered positions of these two vessels would be suggestive of intestinal malrotation instead of pyloric stenosis.[7]

Although the baby is exposed to radiation, an upper GI series (X-rays taken after the baby drinks a special contrast agent) can be diagnostic by showing the pylorus with elongated, narrow lumen and a dent in the duodenal bulb.[7] This phenomenon caused "string sign" or the "railroad track/double track sign" on X-rays after contrast is given. Plain x-rays of the abdomen sometimes shows a dilated stomach.[15]

Although upper gastrointestinal endoscopy would demonstrate pyloric obstruction, physicians would find it difficult to differentiate accurately between hypertrophic pyloric stenosis and pylorospasm.[citation needed]

Blood tests will reveal low blood levels of potassium and chloride in association with an increased blood pH and high blood bicarbonate level due to loss of stomach acid (which contains hydrochloric acid) from persistent vomiting.[16][17] There will be exchange of extracellular potassium with intracellular hydrogen ions in an attempt to correct the pH imbalance. These findings can be seen with severe vomiting from any cause.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]

Infantile pyloric stenosis is typically managed with surgery;[18] very few cases are mild enough to be treated medically.

The danger of pyloric stenosis comes from the dehydration and electrolyte disturbance rather than the underlying problem itself. Therefore, the baby must be initially stabilized by correcting the dehydration and the abnormally high blood pH seen in combination with low chloride levels with IV fluids. This can usually be accomplished in about 24–48 hours.[citation needed]

Intravenous and oral atropine may be used to treat pyloric stenosis. It has a success rate of 85–89% compared to nearly 100% for pyloromyotomy, however it requires prolonged hospitalization, skilled nursing and careful follow up during treatment.[19] It might be an alternative to surgery in children who have contraindications for anesthesia or surgery, or in children whose parents do not want surgery.[citation needed]

Surgery

[edit]The definitive treatment of pyloric stenosis is with surgical pyloromyotomy known as Ramstedt's procedure (dividing the muscle of the pylorus to open up the gastric outlet). This surgery can be done through a single incision (usually 3–4 cm long) or laparoscopically (through several tiny incisions), depending on the surgeon's experience and preference.[20]

Today, the laparoscopic technique has largely supplanted the traditional open repairs which involved either a tiny circular incision around the navel or the Ramstedt procedure. Compared to the older open techniques, the complication rate is equivalent, except for a markedly lower risk of wound infection.[21] This is now considered the standard of care at the majority of children's hospitals across the US, although some surgeons still perform the open technique. Following repair, the small 3mm incisions are hard to see.

The vertical incision, pictured and listed above, is no longer usually required, though many incisions have been horizontal in the past years. Once the stomach can empty into the duodenum, feeding can begin again. Some vomiting may be expected during the first days after surgery as the gastrointestinal tract settles. Rarely, the myotomy procedure performed is incomplete and projectile vomiting continues, requiring repeat surgery. Pyloric stenosis generally has no long term side-effects or impact on the child's future.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

[edit]Males are more commonly affected than females, with firstborn males affected about four times as often, and there is a genetic predisposition for the disease.[22] It is commonly associated with people of Scandinavian ancestry, and has multifactorial inheritance patterns.[9] Pyloric stenosis is more common in Caucasians than Hispanics, Blacks, or Asians. The incidence is 2.4 per 1000 live births in Caucasians, 1.8 in Hispanics, 0.7 in Blacks, and 0.6 in Asians. It is also less common amongst children of mixed race parents.[23] Caucasian male babies with blood type B or O are more likely than other types to be affected.[22]

Infants exposed to erythromycin are at increased risk for developing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, especially when the drug is taken around two weeks of life[24] and possibly in late pregnancy and through breastmilk in the first two weeks of life.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ranells JD, Carver JD, Kirby RS (2011). "Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: epidemiology, genetics, and clinical update". Advances in Pediatrics. 58 (1): 195–206. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2011.03.005. PMID 21736982.

- ^ a b c Georgoula C, Gardiner M (August 2012). "Pyloric stenosis a 100 years after Ramstedt". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 97 (8): 741–5. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2011-301526. PMID 22685043. S2CID 2780184.

- ^ a b Zhu J, Zhu T, Lin Z, Qu Y, Mu D (September 2017). "Perinatal risk factors for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: A meta-analysis". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 52 (9): 1389–1397. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.02.017. PMID 28318599.

- ^ a b Pandya S, Heiss K (June 2012). "Pyloric stenosis in pediatric surgery: an evidence-based review". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 92 (3): 527–39, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2012.03.006. PMID 22595707.

- ^ Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD (February 2017). "Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 30 (1): 30–39. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593429. PMC 5179276. PMID 28144210.

- ^ Hellan M, Lee T, Lerner T (February 2006). "Diagnosis and therapy of primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in adults: case report and review of literature". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 10 (2): 265–9. doi:10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.003. PMID 16455460. S2CID 25249604.

- ^ a b c Naffaa L, Barakat A, Baassiri A, Atweh LA (July 2019). "Imaging Acute Non-Traumatic Abdominal Pathologies in Pediatric Patients: A Pictorial Review". Journal of Radiology Case Reports. 13 (7): 29–43. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v13i7.3443. PMC 6738493. PMID 31558965.

- ^ "Pyloric stenosis: Symptoms". MayoClinic.com. 2010-08-21. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ a b Fried K, Aviv S, Nisenbaum C (November 1981). "Probable autosomal dominant infantile pyloric stenosis in a large kindred". Clinical Genetics. 20 (5): 328–30. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1981.tb01043.x. PMID 7333028. S2CID 40464656.

- ^ Rogers, Ian; Vanderbom, Frederick (2014-02-26). The Consequence and Cause of Pyloric Stenosis of Infancy. More Books Lembert Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-3-659-52125-6.

- ^ Rogers IM (December 2014). "Pyloric stenosis of infancy and primary hyperacidity--the missing link". Acta Paediatrica. 103 (12): e558-60. doi:10.1111/apa.12795. PMID 25178682. S2CID 38564423.

- ^ Kerry Brandis, Acid-Base Physiology Archived 2005-12-10 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ^ Dawes, Laughlin. "Pyloric stenosis | Radiology Case | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Shaoul R, Enav B, Steiner Z, Mogilner J, Jaffe M (March 2004). "Clinical presentation of pyloric stenosis: the change is in our hands" (PDF). The Israel Medical Association Journal. 6 (3): 134–7. PMID 15055266.

- ^ Riggs, Webster; Long, Larry (May 1971). "The Value of the Plain Film Roentgenogram in Pyloric Stenosis". American Journal of Roentgenology. 112 (1): 77–82. doi:10.2214/ajr.112.1.77. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 5582036.

- ^ "Pyloric Stenosis - Clinical Practice Guidelines". The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Bhatt, Binoy; Reddy, Srijaya K. "Chapter 140: Pyloric Stenosis". Access Anesthesiology. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ Askew N (October 2010). "An overview of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis". Paediatric Nursing. 22 (8): 27–30. doi:10.7748/paed.22.8.27.s27. PMID 21066945.

- ^ Aspelund G, Langer JC (February 2007). "Current management of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis". Seminars in Pediatric Surgery. 16 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2006.10.004. PMID 17210480.

- ^ "Medical News:Laparoscopic Repair of Pediatric Pyloric Stenosis May Speed Recovery – in Surgery, Thoracic Surgery from". MedPage Today. 2009-01-16. Archived from the original on 2012-02-23. Retrieved 2012-02-21.

- ^ Sola JE, Neville HL (August 2009). "Laparoscopic vs open pyloromyotomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 44 (8): 1631–7. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.04.001. PMID 19635317.

- ^ a b Dowshen, Steven (November 2007). "Pyloric Stenosis". The Nemours Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Pediatrics, Pyloric Stenosis at eMedicine

- ^ Maheshwai N (March 2007). "Are young infants treated with erythromycin at risk for developing hypertrophic pyloric stenosis?". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 92 (3): 271–3. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.110007. PMC 2083424. PMID 17337692.

- ^ Kong YL, Tey HL (June 2013). "Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation". Drugs. 73 (8): 779–87. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0. PMID 23657872. S2CID 45531743.