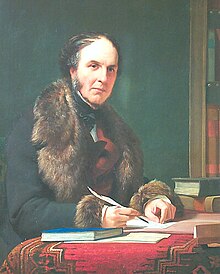

Nassau William Senior

Nassau William Senior | |

|---|---|

Nassau William Senior | |

| Born | 26 September 1790 |

| Died | 4 June 1864 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | English |

| Academic career | |

| Field | Political economy |

| School or tradition | Classical economics |

| Influences | Adam Smith · Alexis de Tocqueville |

Nassau William Senior (/ˈsiːniər/; 26 September 1790 – 4 June 1864), was an English lawyer known as an economist.[1][2] He was also a government adviser over several decades on economic and social policy on which he wrote extensively. In his writings, he made early contributions to theories of value and monopoly.[3]

Early life

[edit]He was born at Compton, Berkshire, the eldest son of Rev. J. R. Senior, vicar of Durnford, Wiltshire.[4] He was educated at Eton College and Magdalen College, Oxford; at university he was a private pupil of Richard Whately, afterwards Archbishop of Dublin with whom he remained connected by ties of lifelong friendship. He took the degree of B.A. in 1811 and became a Vinerian Scholar in 1813.

Career

[edit]Senior went into the field of conveyancing, with a pupilage under Edward Burtenshaw Sugden. When Sugden rather abruptly informed his pupils in 1816 that he was concentrating on chancery work, Senior took steps to qualify as a Certified Conveyancer, which he did in 1817. With one other pupil, Aaron Hurrill, he then took over Sugden's practice.[5][6] Senior was called to the bar in 1819, but problems with public speaking limited his potential career as an advocate. In 1836, during the chancellorship of Lord Cottenham, he was appointed a master in chancery.

On the foundation of the Drummond professorship of political economy at Oxford in 1825, he was elected to fill the chair, which he occupied until 1830 and again from 1847 to 1852. In 1830, he was requested by Lord Melbourne to inquire into the state of combinations and strikes, report on the state of the law and suggest improvements.

Senior was a member of the Poor Law Inquiry Commission of 1832, and of the Royal Commission of 1837 on handloom weavers. The report of the latter, published in 1841, was drawn up by him and had the substance of the report he had prepared some years earlier, on combinations and strikes.

Later life

[edit]Senior became a good friend of Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) whom he met in 1833 for the first time before the publishing of Democracy in America.[7]

Senior was in the spring of 1849 legal advisor and counsellor to Jenny Lind, who then was performing in London. She intended to marry a soldier named Harris, and Senior was supposed to draw up marriage settlements. Harriet Grote in correspondence calls him Claudius Harris, a lieutenant of the Madras Cavalry; the Grote connection was that he was the brother of the wife of Joseph Grote, the brother of her husband, George.[8][9] Senior accompanied Lind and Harriet Grote to Paris (amid civil strife and a cholera epidemic).[10] The marriage failed to take place.[11]

Senior was "indirectly responsible for the contract which Jenny Lind condescended to sign in 1850 with the American promoter P. T. Barnum".[12][13]

Senior was one of the commissioners appointed in 1864 to inquire into popular education in England. He died at Kensington that year.

Writings

[edit]Senior was a contributor to the Quarterly Review, Edinburgh Review, London Review and North British Review. In their pages, he dealt with literary as well as with economic and political subjects. The London Review was a project of Senior from 1828, for a quarterly periodical. It was backed by Richard Whately and others of the Oriel Noetics, and with the help of Thomas Mayo, he found an editor in Joseph Blanco White. Early contributions from John Henry Newman, Edwin Chadwick and Senior himself (on the Waverley novels and William Jacob's views) were not enough to establish it, and it ceased publication in mid-1829.[14]

Economics

[edit]His writings on economic theory consisted of an article in the Encyclopædia Metropolitana, afterwards separately published as An Outline of the Science of Political Economy (1836), and his lectures delivered at Oxford. Of the latter, the following were printed:

- An Introductory Lecture on Political Economy (London: John Murray, 1827).

- Two Lectures on Population, with a correspondence between the author and Malthus (1829).[15]

- Three Lectures on the Transmission of the Precious Metals from Country to Country, and the Mercantile Theory of Wealth (1828).

- Three Lectures on the Cost of obtaining Money, and on some Effects of Private and Government Paper Money (London: John Murray, 1830).

- Three Lectures on the Rate of Wages (1830, 2nd ed. 1831).[16]

- A Lecture on the Production of Wealth (1847).

- Four Introductory Lectures on Political Economy (1852).

Several of his lectures were translated into French by M. Arrivabne under the title of Principes Fondamentaux d'Economie Politique (1835).

Social questions

[edit]Senior also wrote on administrative and social questions:

- Report on the Depressed State of the Agriculture of the United Kingdom. In: The Quarterly Review (1821), pp. 466–504

- A Letter to Lord Howick on a Legal Provision for the Irish Poor, Commutation of Tithes and a Provision for the Irish Roman Catholic Clergy (1831, 3rd ed., 1832, with a preface containing suggestions as to the measures to be adopted in the present emergency)

- Statement of the Provision for the Poor and of the Condition of the Laboring Classes in a considerable portion of America and Europe, being the Preface to the Foreign Communications in the Appendix to the Poor Law Report (1835)

- On National Property, and on the Prospects of the Present Administration and of their Successors (anon.; 1835)

- Letters on the Factory Act, as it affects the Cotton Manufacture (1837)

- Suggestions on Popular Education (1861)

- American Slavery (in part a reprint from the Edinburgh Review, 1862)

- An Address on Education delivered to the Social Science Association (1863)

His contributions to the reviews were collected in volumes entitled Essays on Fiction (1864); Biographical Sketches (1865, chiefly of noted lawyers); and Historical and Philosophical Essays (1865).

In 1859 appeared his Journal kept in Turkey and Greece in the Autumn of 1857 and the Beginning of 1858; and the following were edited after his death by his daughter:

- Journals, Conversations and Essays relating to Ireland (1868)

- Journals kept in France and Italy from 1848 to 1852, with a Sketch of the Revolution of 1848 (1871)[17]

- Conversations with Thiers, Guizot and other Distinguished Persons during the Second Empire (1878)

- Conversations with Distinguished Persons during the Second Empire, from 1860 to 1863 (1880)

- Conversations and Journals in Egypt and Malta (1882)

- also in 1872 Correspondence and Conversations with Alexis de Tocqueville from 1834 to 1859.

Senior's tracts on practical politics, though the theses they supported were sometimes questionable, were ably written and are still worth reading but cannot be said to be of much permanent interest. His name continues to hold an honorable, though secondary, place in the history of political economy. In the later years of his life, during his visits to foreign countries, he noted the political and social phenomena that they exhibited. Several volumes of his journals were published.

Political economy

[edit]Senior regarded political economy as a deductive science, of inferences from four elementary propositions, which are not assumptions but facts. It concerns itself, however, with wealth only and can therefore give no political advice. He pointed out inconsistencies of terminology in David Ricardo's works: for example, his use of value in the sense of cost of production, high and low wages in the sense of a certain proportion of the product as dilute amount and his employment of the epithets fixed and circulating as applied to capital.[clarification needed] He argued, too, that in some cases the premises assumed by Ricardo are false. He cited the assertions that rent depends on the difference of fertility of the different portions of land in cultivation; that the laborer always receives precisely the necessaries or what custom leads him to consider the necessaries, of life; that as wealth and population advance, agricultural labor becomes less and less proportionately productive and therefore the share of the produce taken by the landlord and the laborer must constantly increase, but that taken by the capitalist must constantly diminish. He denied the truth of all the propositions.

Besides adopting some terms, such as that of natural agents, from Jean-Baptiste Say, Senior introduced the term "abstinence" to express the conduct of the capitalist that is remunerated by interest. He added some considerations to what had been said by Adam Smith on the division of labor and distinguished between the rate of wages and the price of labor but assumed a determinate wage-fund.

Senior's 1837 Letters on the Factory Act have become notorious for the analytical mistake made in them. Nassau opposed the Child Labour Law and the proposed Ten Hours Act, on the grounds that they would make it impossible for factory owners to make profits. In Senior's analysis of factory production, capital advanced means of subsistence (wage) to the workers, who would then return the advance during the first 101⁄2 hours of their labor, producing a profit only in the last hour. What Senior failed to realize is that the turnover of capital stock depends on the length of the working day; he assumed it constant.[18]

In Karl Marx's first volume of Capital, Senior's analyses are subjected to a series of exacting criticisms. "If, giving credence to the out-cries of the manufacturers, he believed that the workmen spend the best part of the day in the production, i.e., the reproduction or replacement of the value of the buildings, machinery, cotton, coal, &c.," Marx writes, "then his analysis was superfluous."[19]

Senior modified his opinions on population in the course of his career and asserted that in the absence of disturbing causes, subsistence may be expected to increase in a greater ratio than population. Charles Périn argued that he set up "egoism" as the guide of practical life. Thomas Edward Cliffe Leslie attacked the abstraction implied in the phrase "desire of wealth".

Controversy on Irish Famine

[edit]Senior reportedly said of the Great Irish Famine of 1845

"would not kill more than one million people, and that would scarcely be enough to do any good".[20]

That is a point quoted by theorists who propose that the actions of the British government before and during the famine were tantamount to deliberate genocide, but his opinion was not government policy. Costigan[21] argues, however, that the quote is taken out of context and reflects Senior's opinion purely from the viewpoint of the theory of political economy; in other words, even such a large reduction in the population would not solve the underlying economic, social and political problems, which would be proved correct. He argues that Senior made attempts over many years to improve the lot of the Irish people, even at considerable personal cost (in 1832, he was removed, after one year in office, from his position as Professor of Political Economy at King's College, London, for supporting the Catholic Church in Ireland). In his letter[22] of 8 January 1836 to Lord Howick, Senior wrote,

With respect to the ejected tenantry, the stories that are told make one's blood boil. I must own that I differ from most persons as to the meaning of the words 'legitimate influence of property'. I think that the only legitimate influence is example and advice, and that a landlord who requires a tenant to vote in opposition to the tenant's feeling of duty is the suborner of a criminal act.'

Senior's notes of his visits to Birr, County Offaly in the 1850s mention his surprise and concern that the everyday lifestyle of the Irish poor had changed so little, despite the famine disaster.

- Though the aspect of Ireland is somewhat changed since 1852, and much since 1844, I doubt whether any great real alteration in the habits to feelings of the people has taken place. They still depend mainly on the potato. They still depend rather on the occupation of land, than on the wages of labour. They still erect for themselves the hovels in which they dwell. They are still eager to subdivide and to sublet. They are still the tools of their priests, and the priests are still ignorant of the economical laws on which the welfare of the labouring classes depends.[23]

Family

[edit]Senior married Mary Charlotte Mair of Iron Acton, Gloucestershire, in 1821. Their daughter, the memoirist Mary Charlotte Mair Simpson (1825–1907) acted as his literary executor. Their son Nassau John Senior (1822–1891), was a lawyer and married Jane Elizabeth Senior (1828–1877), an inspector of workhouses and schools.[24]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Bowley, Marian (1936). "Nassau Senior's Contribution to the Methodology of Economics". Economica. 3 (11): 281–305. doi:10.2307/2549222. ISSN 0013-0427.

- ^ Anderson, Gary M.; Ekelund, Robert B.; Tollison, Robert D. (1989). "Nassau Senior as Economic Consultant: The Factory Acts Reconsidered". Economica. 56 (221): 71–81. doi:10.2307/2554496. ISSN 0013-0427.

- ^ Ely, Richard T. (1900). "Senior's Theory of Monopoly". Publications of the American Economic Association. 1 (1): 89–102. ISSN 1049-7498. JSTOR 2485824.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Senior, Nassau William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 644–645.

- ^ Leon Levy 1970, p. 41.

- ^ S. Leon Levy, "Nassau W. Senior, British Economist, in the Light of Recent Researches: I", Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 26, No. 4 (Apr., 1918), pp. 350–351. Published by The University of Chicago Press. Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1822589

- ^ Preface of Correspondence and Conversations of Alexis de Tocqueville with Nassau William Senior 1834–1859, edited by M. C. M. Simpson (Senior's daughter), New York 1872.

- ^ Jenny Lind – The Artist. Memoir of Madame Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt: Her Early Art-Life and Dramatic Career, 1820–1850 by H. S. Holland, W.S. Rockstro and Otto Goldschmidt, London 1891 (vol. I, p. xi and vol. II, pp. 344–347); and S. Leon Levy, Nassau W. Senior 1790–1864, Devon 1970 (pp. 171–173).

- ^ Thomas Herbert Lewin, The Lewin Letters; a selection from the correspondence & diaries of an English family, 1756–1884 (1909), pp. 63–65; archive.org.

- ^ Senior's handwritten letter dated 1849 Paris – Monday [21 May] tells his daughter in London: "We are here on the brink of another fight.... Mrs Grote is puzzled. She does not wish to stay over the émeute – does not like to leave Jenny" (copy from The National Archives, Wales).

- ^ Senior's handwritten letter of 28 May 1849 tells Mrs Grote who is still in Paris with Jenny Lind: "Lord Liverpool says that Jenny ought to write not direct to the Queen, but to G. Anson [the Queen's Privy Purse] – to say that as Her Majesty had done her the honor to express a wish to be informed when this marriage was to take place, he thought it wise to tell to him for her Majesty's information that it will never take place" (copy from The National Archives, Wales). Icons of Europe says that Jenny Lind had planned to marry Chopin and not "Captain" Harris, who, according to British Army records, was a cadet / lieutenant stationed in India at the time (source: Cecilia and Jens Jorgensen, Chopin and The Swedish Nightingale, Brussels 2003, ISBN 2-9600385-0-9, and their subsequent research in consultation with the Fryderyk Chopin Institute and other institutions).

- ^ Leon Levy 1970, p. 171

- ^ Did Senior also assist Jenny Lind in obtaining permission for Chopin's lavish funeral at Église de la Madeleine on 30 October 1849, which she – as said by Icons of Europe – appears to have secretly organized? He met with French foreign minister Alexis de Tocqueville in Paris on 21–23 October 1849 for apparently no good reason (Correspondence and Conversations of Alexis de Tocqueville with Nassau William Senior 1834–1859, M.C.M. Simpson, New York 1872, p. 68).

- ^ Leon Levy 1970, pp. 60–64.

- ^ online available (2011-06-24)

- ^ online available (2011-06-24)

- ^ "Review of Journals kept in France and Italy from 1848 to 1852 by the late Nassau William Senior, edited by his daughter M. C. M. Simpson, 2 vols". The Athenaeum (2281): 77–78. 15 July 1871.

- ^ DeLong, J. Bradford (1986). "Senior's 'last hour': suggested explanation of a famous blunder" (PDF). History of Political Economy. 18 (2): 325–333. doi:10.1215/00182702-18-2-325.

- ^ "Economic Manuscripts: Capital Vol. I – Chapter Nine".

- ^ Gallagher, Michael & Thomas, Paddy's Lament. Harcourt Brace & Company, New York / London, 1982.

- ^ Costigan, Giovanni 'A History of Modern Ireland', Pegasus, New York, p. 185.

- ^ Leon Levy 1970, p. 268.

- ^ Offaly history pages on Senior's visits Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Deane, Phyllis. "Senior, Nassau William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25090. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

References

[edit]- Levy, S. Leon (1943). Nassau W. Senior, The Prophet of Modern Capitalism, Boston, Massachusetts: Bruce Humphries. OCLC 730126628

- Levy, S. Leon (1970). Nassau W. Senior 1790–1864, Newton Abbot : David & Charles. OCLC 463277765

- Smith, George H. (2008). "Senior, Nassau William (1790–1864)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 457–58. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n279. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.