Salyut 7

Salyut 7 photographed by Soyuz T-13 crew before docking, 25 September 1985 | |

The insignia of the Salyut Program | |

| Station statistics | |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1982-033A |

| SATCAT no. | 13138 |

| Launch | 19 April 1982, 19:45:00 UTC |

| Carrier rocket | Proton-K No. 306-02 |

| Launch pad | Baikonur, Site 200/40 |

| Reentry | 7 February 1991[1] |

| Mass | 19,824 kg (43,704 lb) |

| Length | 16 m (52 ft) min.[1] |

| Width | 4.15 m (13.6 ft) max.[1] |

| Pressurised volume | 90 m3 (3,200 cu ft) min.[1] |

| Periapsis altitude | 219 km (136 mi; 118 nmi) |

| Apoapsis altitude | 278 km (173 mi; 150 nmi) |

| Orbital inclination | 51.6° |

| Orbital period | 89.21 minutes |

| Days in orbit | 3,215 days |

| Days occupied | 816 days |

| No. of orbits | 51,917 |

| Distance travelled | 2,106,297,129 km (1,137,309,460 nmi) |

| Statistics as of de-orbit and reentry | |

| Configuration | |

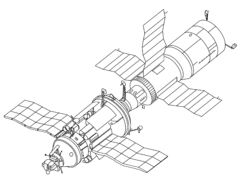

Salyut 7 with docked Kosmos 1686 TKS spacecraft | |

Salyut 7 (Russian: Салют-7, lit. 'Salute 7'), also known as DOS-6 (Durable Orbital Station 6)[1] was a space station in low Earth orbit from April 1982 to February 1991.[1] It was first crewed in May 1982 with two crew via Soyuz T-5, and last visited in June 1986, by Soyuz T-15.[1] Various crew and modules were used over its lifetime, including 12 crewed and 15 uncrewed launches in total.[1] Supporting spacecraft included the Soyuz T, Progress, and TKS spacecraft.[1]

It was part of the Soviet Salyut programme, and launched on 19 April 1982 on a Proton-K rocket from Site 200/40 at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in the Soviet Union. Salyut 7 was part of the transition from monolithic to modular space stations, acting as a testbed for docking of additional modules and expanded station operations. It was the eighth space station of any kind launched. Salyut 7 was the last of both the second generation of DOS-series space stations and of the monolithic Salyut Program overall, to be replaced by Mir, the modular, expandable, third generation.

Description

[edit]Salyut 7 was the backup vehicle for Salyut 6 and was very similar in equipment and capabilities. With delays to the Mir programme it was decided to launch the back-up vehicle as Salyut 7. In orbit the station suffered technical failures though it benefited from the improved payload capacity of the visiting Progress and Soyuz craft and the experience of its crews who improvised many solutions (such as a fuel line rupture in September 1983 requiring EVAs by the Soyuz T-10 crew to repair). It was aloft for eight years and ten months (a record not broken until Mir), during which time it was visited by 10 crews constituting six main expeditions and four secondary flights (including French and Indian cosmonauts). The station also saw two flights of Svetlana Savitskaya making her the second woman in space since Valentina Tereshkova first flew in June 1963 and the first woman to perform an EVA during which she conducted metal cutting and welding alongside her colleague Vladimir Dzhanibekov.[2] Aside from the many experiments and observations made on Salyut 7, the station also tested the docking and use of large modules with an orbiting space station. The modules were called "Heavy Kosmos modules" though in reality were variants of the TKS intended for the cancelled Almaz military space station. They helped engineers develop the technology necessary to build Mir.

Equipment

[edit]

It had two docking ports, one on either end of the station, to allow docking with the Progress uncrewed resupply craft, and a wider front docking port to allow safer docking with a Heavy Kosmos module. It carried three solar panels, two in lateral and one in dorsal longitudinal positions, but they now had the ability to mount secondary panels on their sides. Internally, the Salyut 7 carried electric stoves, a refrigerator, constant hot water and redesigned seats at the command console (more like bicycle seats). Two portholes were designed to allow ultraviolet light in, to help kill infections.[1] The medical, biological and exercise sections were improved, to allow long stays in the station. The BST-1M telescope used in Salyut 6 was replaced by an X-ray detection system.[3]

To support experiments in cultivating plants in space, several different plant life support systems were installed: Oasis 1A, Vazon, Svetoblok, Magnetogravistat, Biogravistat and Fiton(Phyton)-3. It was in Fiton-3 that Arabidopsis became the first plants to flower and produce seeds in the zero gravity of space.

Salyut 7 was the most advanced and comfortable space station of the Salyut series. A set of modifications to the interior made it more liveable. There were approximately 20 windows with shades on the Salyut 7. To protect the inside of the windows, they were covered with removable glass panels. The colour scheme was improved and a refrigerator was installed. The ceiling on the Salyut 7 was white; the left wall was apple green and the right one beige,[4][5] a signature design by interior design architect, Galina Balashova, who carried on the concept through Soyuz to Mir and Buran, in an effort to replace 'survive' with 'comfort', working with seasoned cosmonauts to make living conditions better and 'closer to home'[6][7] Externally, in a departure from previous first generation stations, the large diameter operations section which housed the large scientific apparatus, was colored in a distinctive brown-red and white stripe pattern. This was done to differentiate between it and the outwardly similar Salyut 6 that, for several months of its life, was in orbit at the same time.

Crews and missions

[edit]

Following up the use of Kosmos 1267 on Salyut 6, the Soviets launched Kosmos 1443 on 2 March 1983 from a Proton SL-13. It docked with the station on 10 March, and was used by the crew of Soyuz T-9. It jettisoned its recovery module on 23 August, and re-entered the atmosphere on 19 September. Kosmos 1686 was launched on 27 September 1985, docking with the station on 2 October. It did not carry a recovery vehicle, and remained connected to the station for use by the crew of Soyuz T-14. Ten Soyuz T crews operated in Salyut 7. Only two Interkosmos "guest cosmonauts" worked in Salyut 7. The first attempt to launch Soyuz T-10 was aborted on the launch pad when a fire broke out at the base of the vehicle. The payload was ejected, and the crew was recovered safely.

Salyut 7 was the first manned space vehicle to launch a satellite, when it fired the small experimental Iskra 2 satellite out of its waste airlock. This was performed mainly to deprive the US Space Shuttle of becoming the first manned spacecraft to launch a satellite.[8]

Resident crews

[edit]Salyut 7 had six resident crews.

- The first crew, Anatoli Berezovoy and Valentin Lebedev, arrived on 13 May 1982 on Soyuz T-5 and remained for 211 days until 10 December 1982.[1]

- On 27 June 1983, the crew of Vladimir Lyakhov and Alexander Alexandrov arrived on Soyuz T-9 and remained for 150 days, until 23 November 1983.

- On 8 February 1984, Leonid Kizim, Vladimir Solovyov and Oleg Atkov began a 237-day stay, the longest on Salyut 7, which ended on 2 October 1984.

- Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Viktor Savinykh (Soyuz T-13) arrived at the space station on 6 June 1985 to repair its malfunctions.

- On 17 September 1985, Soyuz T-14 docked with the station carrying Vladimir Vasyutin, Alexander Volkov and Georgi Grechko. Eight days later Dzhanibekov and Grechko left the station and returned to Earth after 103 days, while Savinyikh, Vasyutin and Volkov remained on Salyut 7 and returned to Earth on 21 November 1985 after 65 days.

- On 6 May 1986, Soyuz T-15 carrying Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov docked with the space station and undocked, after a 50-day stay, on 25 June 1986. The Soyuz had come from the Mir space station and returned to Mir on 26 June 1986 in a flight lasting 29 hours.

There were also four visiting missions, crews which came to bring supplies and make shorter duration visits with the resident crews.

Technical and crew problems

[edit]The station suffered from two major problems, the first of which required extensive repair work to be performed on a number of EVAs.

Leaks

[edit]On 9 September 1983, during the stay of Vladimir Lyakhov and Alexander Alexandrov, while reorienting the station to perform a radiowave transmission experiment, Lyakhov noticed the pressure of one fuel tank was almost zero. Following this, Alexandrov spotted a fuel leak when looking through the aft porthole. Ground control decided to try to repair the damaged pipes, in what was the most complex repair attempted during EVA at the time. This was to be attempted by the next crew, the current one lacking the necessary training and tools. The damage was eventually repaired by Leonid Kizim and Vladimir Solovyov, who needed four EVAs to fix two leaks. A special tool to fix the third leak was delivered by Soyuz T-12, and the leak was subsequently fixed.[9]

Loss of power

[edit]On 11 February 1985, contact with Salyut 7 was lost. The station began to drift, making unpredictable movements in orbit, and all systems shut down. At this time the station was uninhabited, after the departure of Leonid Kizim, Vladimir Solovyov and Oleg Atkov, and before the next crew arrived. It was once again decided to attempt to repair the station. The work was performed by Vladimir Dzhanibekov and Viktor Savinykh on the Soyuz T-13 mission during June 1985, in what was in the words of author David S. F. Portree "one of the most impressive feats of in-space repairs in history".[1] This operation forms the basis of the 2017 Russian film Salyut 7.

All Soviet and Russian space stations were equipped with automatic rendezvous and docking systems, from the first space station Salyut 1 using the Igla system, to the Russian Orbital Segment of the International Space Station using the Kurs system. Upon arrival, on 6 June 1985, the Soyuz crew found the station was not broadcasting radar or telemetry for rendezvous, and after arrival and external inspection of the tumbling station, the crew estimated proximity using handheld laser rangefinders.[10]

Dzhanibekov piloted his ship to intercept the forward port of Salyut 7 and matched the station's rotation. After hard docking to the station and confirming the station's electrical system was dead, Dzhanibekov and Savinykh sampled the station atmosphere prior to opening the hatch. Attired in winter fur-lined clothing, they entered the station to conduct repairs. The fault was eventually found to be an electrical sensor that determined when the batteries needed charging.

Once the batteries were replaced, the station started charging them, and warmed up over the next few days.[9] Within a week sufficient systems were brought back online to allow uncrewed Progress cargo ships to dock with the station.[1]

End of life

[edit]

Salyut 7 was last inhabited in 1986 by the crew of Soyuz T-15, who ferried equipment from Salyut 7 to the new Mir space station. Between 19 and 22 August 1986, engines on Kosmos 1686 boosted Salyut 7 to a record-high mean orbital altitude of 475 km to forestall reentry until 1994. Retrieval at a future date by a Buran shuttle was also planned.[11]

However, unexpectedly high solar activity in the late 1980s and early 1990s increased atmospheric drag on the station and sped its orbital decay. It finally underwent an uncontrolled reentry on 7 February 1991 over the town of Capitán Bermúdez in Argentina after it overshot its intended entry point, which would have placed its debris in uninhabited portions of the southern Pacific Ocean.[12][13]

Expeditions and visiting spacecraft

[edit]Notation:

- EO (Russian: ЭО, Экспедиция Основная) or PE means Principal Expedition

- EP (Russian: ЭП, Экспедиция Посещения) or VE means Visiting Expedition

Expeditions

[edit]| Expedition | Crew | Launch date | Flight up | Landing date | Flight down |

Duration (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salyut 7 – EO-1 | Anatoli Berezovoy, Valentin Lebedev[1] |

13 May 1982 09:58:05 UTC |

Soyuz T-5 | 10 December 1982 19:02:36 UTC |

Soyuz T-7 | 211.38 |

| Salyut 7 – EP-1 | Vladimir Dzhanibekov, Aleksandr Ivanchenkov, Jean-Loup Chrétien – France |

24 June 1982 16:29:48 UTC |

Soyuz T-6 | 2 July 1982 14:20:40 UTC |

Soyuz T-6 | 7.91 |

| Salyut 7 – EP-2 | Leonid Popov, Aleksandr Serebrov, Svetlana Savitskaya |

19 August 1982 17:11:52 UTC |

Soyuz T-7 | 27 August 1982 15:04:16 UTC |

Soyuz T-5 | 7.91 |

| Salyut 7 – EO-2 | Vladimir Lyakhov, Aleksandr Pavlovich Aleksandrov |

27 June 1983 09:12:00 UTC |

Soyuz T-9 | 23 November 1983 19:58:00 UTC |

Soyuz T-9 | 149.45 |

| Salyut 7 – EO-3 | Leonid Kizim, Vladimir Solovyov, Oleg Atkov |

8 February 1984 12:07:26 UTC |

Soyuz T-10 | 2 October 1984 10:57:00 UTC |

Soyuz T-11 | 236.95 |

| Salyut 7 – EP-3 | Yury Malyshev, Gennady Strekalov, Rakesh Sharma – India |

3 April 1984 13:08:00 UTC |

Soyuz T-11 | 11 April 1984 10:48:48 UTC |

Soyuz T-10 | 7.90 |

| Salyut 7 – EP-4 | Vladimir Dzhanibekov, Svetlana Savitskaya, Igor Volk |

17 July 1984 17:40:54 UTC |

Soyuz T-12 | 29 July 1984 12:55:30 UTC |

Soyuz T-12 | 11.80 |

| Salyut 7 – EO-4-1a | Viktor Savinykh | 6 June 1985 06:39:52 UTC |

Soyuz T-13 | 21 November 1985 10:31:00 UTC |

Soyuz T-14 | 168.16 |

| Salyut 7 – EO-4-1b | Vladimir Dzhanibekov | 6 June 1985 06:39:52 UTC |

Soyuz T-13 | 26 September 1985 09:51:58 UTC |

Soyuz T-13 | 112.13 |

| Salyut 7 – EP-5 | Georgi Grechko | 17 September 1985 12:38:52 UTC |

Soyuz T-14 | 26 September 1985 09:51:58 UTC |

Soyuz T-13 | 8.88 |

| Salyut 7 – EO-4-2 | Vladimir Vasyutin, Alexander Volkov |

17 September 1985 12:38:52 UTC |

Soyuz T-14 | 21 November 1985 10:31:00 UTC |

Soyuz T-14 | 64.91 |

| Salyut 7 – EO-5 | Leonid Kizim, Vladimir Solovyov |

13 March 1986 12:33:09 UTC |

Soyuz T-15 | 16 July 1986 12:34:05 UTC |

Soyuz T-15 | 125.00 50 on S7 |

Spacewalks

[edit]| Spacecraft | Spacewalker | Start – UTC | End – UTC | Duration | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salyut 7 – PE-1 – EVA 1 | Lebedev, Berezevoi[1] | 30 July 1982 02:39 |

30 July 1982 05:12 |

2 h, 33 min | Retrieve experiments |

| Salyut 7 – PE-2 – EVA 1 | Lyakhov, Alexandrov | 1 November 1983 04:47 |

1 November 1983 07:36 |

2 h, 50 min | Add solar array |

| Salyut 7 – PE-2 – EVA 2 | Lyakhov, Alexandrov | 3 November 1983 03:47 |

3 November 1983 06:42 |

2 h, 55 min | Add solar array |

| Salyut 7 – PE-3 – EVA 1 | Kizim, Solovyov | 23 April 1984 04:31 |

23 April 1984 08:46 |

4 h, 20 min | ODU repair |

| Salyut 7 – PE-3 – EVA 2 | Kizim, Solovyov | 26 April 1984 02:40 |

26 April 1984 07:40 |

4 h, 56 min | Repair ODU |

| Salyut 7 – PE-3 – EVA 3 | Kizim, Solovyov | 29 April 1984 01:35 |

29 April 1984 04:20 |

2 h, 45 min | Repair ODU |

| Salyut 7 – PE-3 – EVA 4 | Kizim, Solovyov | 3 May 1984 23:15 |

4 May 1984 02:00 |

2 h, 45 min | Repair ODU |

| Salyut 7 – PE-3 – EVA 5 | Kizim, Solovyov | 18 May 1984 17:52 |

18 May 1984 20:57 |

3 h, 05 min | Add solar array |

| Salyut 7 – VE-4 – EVA 1 | Savitskaya, Dzhanibekov | 25 July 1984 14:55 |

25 July 1984 18:29 |

3 h, 35 min | First woman EVA |

| Salyut 7 – PE-3 – EVA 6 | Kizim, Solovyov | 8 August 1984 08:46 |

8 August 1984 13:46 |

5 h, 00 min | Complete ODU repair |

| Salyut 7 – PE-4 – EVA 1 | Dzhanibekov, Savinykh | 2 August 1985 07:15 |

2 August 1985 12:15 |

5 h, 00 min | Augment solar arrays |

| Salyut 7 – PE-6 – EVA 1 | Kizim, Solovyov | 28 May 1986 05:43 |

28 May 1986 09:33 |

3 h, 50 min | Test truss, retrieve samples |

| Salyut 7 – PE-6 – EVA 2 | Kizim, Solovyov | 31 May 1986 04:57 |

31 May 1986 09:57 |

5 h, 00 min | Test truss |

Docking operations

[edit]On three occasions, a visiting Soyuz craft was transferred from the station's aft port to its forward port. This was done to accommodate upcoming Progress shuttles, which could only refuel the station using connections available at the aft port. Typically, the resident crew would first dock at the forward port, leaving the aft port available for Progress craft and visiting Soyuz support crews. When a support crew docked at the aft port and left in the older, forward Soyuz, the resident crew would move the new vehicle forward by boarding it, undocking, and translating some 100–200 meters away from Salyut 7. Then, ground control would command the station itself to rotate 180 degrees, and the Soyuz would close and re-dock at the forward port. Soyuz T-7, T-9 and T-11 performed the operation, piloted by resident crews.[1]

Specifications

[edit]Specifications of the baseline 1982 Salyut 7 module, from Mir Hardware Heritage (1995, NASA RP1357):[1]

- Length – about 16 m

- Maximum diameter – 4.15 meters

- Habitable volume – 90 m³

- Weight at launch – 19,824 kg

- Launch vehicle – Proton rocket (three-stage)

- Orbital inclination – 51.6°

- Span across solar arrays – 17 m

- Area of solar arrays – 51 m2

- Number of solar arrays – 3

- Electricity available – 4.5 kW

- Resupply carriers – Soyuz-T, Progress, TKS spacecraft

- Docking System – Igla or manual approach

- Number of docking ports – 2

- Total crewed missions – 12

- Total uncrewed missions – 15

- Total long-duration missions – 6

- Number of main engines – 2

- Main engine thrust (each) – 300 kg

Visiting spacecraft and crews

[edit](Launched crews. Spacecraft launch and landing dates listed.)

- Soyuz T-5 – 13 May – 27 August 1982

- Soyuz T-6 – 24 June – 2 July 1982 – Intercosmos Flight

- Soyuz T-7 – 19 August – 10 December 1982

- Soyuz T-8 – 20–22 April 1983 – Failed docking

- Soyuz T-9 – 27 June – 23 November 1983

- Soyuz T-10-1 – 26 September 1983 – Launch abort

- Soyuz T-10 – 8 February – 11 April 1984

- TKS 3 – 4 March – 14 August 1983 – Launched uncrewed as Kosmos 1443.

- Soyuz T-11 – 3 April – 2 October 1984 – Intercosmos Flight

- Soyuz T-12 – 17–29 July 1984

- Soyuz T-13 – 6 June – 26 September 1985

- Soyuz T-14 – 17 September – 21 November 1985

- TKS 4 – September 1985 – 7 February 1991 – Launched uncrewed as Kosmos 1686. Featured a high-resolution photo apparatus and optical sensor experiments (infrared telescope and Ozon spectrometer).

- Soyuz T-15 – 13 March – 16 July 1986 – Also visited Mir

In popular culture

[edit]The repair and reactivation of the station by Soyuz T-13 is the subject of the 2017 Russian historical drama Salyut 7. These events also served as a plot base for the Polish novel Połowa nieba (pol. Half the sky), by Bartek Biedrzycki (first published 2018), collected in Zimne światło gwiazd in 2020.

See also

[edit]- List of spacewalks

- Skylab

- STS-61 (Hubble Space Telescope mirror fix-mission)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q David S. F. Portree (1995). Mir Hardware Heritage (PDF). NASA. pp. 90–102. NASA-SP-4225. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023.

- ^ Suzy (16 July 2009). "Space welding anniversary!". Orbiter-Forum. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Salyut 7". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Sandra Häuplik-Meusburger (2011). Architecture for Astronauts: An Activity-based Approach. Vienna: Springer. ISBN 978-3-709-10667-9. OCLC 759926461.

- ^ B. J. Bluth; M. Helppie (1 August 1986). Soviet Space Stations as Analogs (PDF) (2nd ed.). NASA. OCLC 33099311. NASA-CR-180920.

- ^ Jonathan Bell (July 2015). "Soviet space programme: Philipp Meuser lifts the lid on the seminal cosmic design of Galina Balashova". www.wallpaper.com. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Philipp Meuser; Clarice Knowles (2015). Galina Balashova: Architect of the Soviet Space Programme. Berlin: DOM Publishers. ISBN 978-3-86922-355-1. OCLC 903080663.

- ^ John Noble Wilford (19 May 1982). "Soviet Craft Launches Satellite". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ a b Robert Zimmerman (2003). Leaving Earth: Space Stations, Rival Superpowers & the Quest for Interplanetary Travel. J. Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09739-0.

- ^ Nickolai Belakovski (16 September 2014). "The little-known Soviet mission to rescue a dead space station". Ars Technica. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Mark Wade. "Salyut 7". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ "Spacecraft Reentry FAQ:". www.aero.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ John T. McQuiston (7 February 1991). "Salyut 7, Soviet Station in Space, Falls to Earth After 9-Year". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 October 2009.