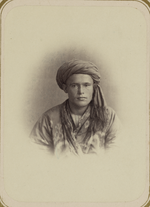

Tajiks

a photo of Tajiks taken in Tajikistan, 2018 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 19–26 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 8-15 million (2024)[1] [2] | |

| ~8,700,000 (2024)[3] [4] | |

| ~1,700,000 (2021)[5] other, non-official, scholarly estimates are 6-7 million[6][7] | |

| 350,236[8] | |

| 58,913[9] | |

| 52,000[a] | |

| 50,121[11] | |

| 39,642[12] | |

| 4,255[13] | |

| Languages | |

| Persian (Dari and Tajik) Secondary: Pashto, Russian, Uzbek | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam[14] minority Shia Islam[15] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Iranian peoples | |

Tajiks (Persian: تاجيک، تاجک, romanized: Tājīk, Tājek; Tajik: Тоҷик, romanized: Tojik) are a Persian-speaking[16] Eastern Iranian ethnic group native to Central Asia, living primarily in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. Tajiks are the largest ethnicity in Tajikistan, and the second-largest in Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. More Tajiks live in Afghanistan than Tajikistan. They speak varieties of Persian, a Western Iranian language. In Tajikistan, since the 1939 Soviet census, its small Pamiri and Yaghnobi ethnic groups are included as Tajiks.[17] In China, the term is used to refer to its Pamiri ethnic groups, the Tajiks of Xinjiang, who speak the Eastern Iranian Pamiri languages.[18][19] In Afghanistan, the Pamiris are counted as a separate ethnic group.[20]

As a self-designation, the literary New Persian term Tajik, which originally had some previous pejorative usage as a label for eastern Persians or Iranians,[21][22] has become acceptable during the last several decades, particularly as a result of Soviet administration in Central Asia.[16] Alternative names for the Tajiks are Fārsīwān (Persian-speaker), and Dīhgān (cf. Tajik: Деҳқон) which translates to "farmer or settled villager", in a wider sense "settled" in contrast to "nomadic" and was later used to describe a class of land-owning magnates as "Persian of noble blood" in contrast to Arabs, Turks and Romans during the Sassanid and early Islamic period.[23][21]

The Tajiks have a mixed origin, and are primarily descended from Bactrians, Sogdians, Scythians, but also Persians, and various Turkic peoples of Central Asia,[24][25] all of whom are known to have inhabited the region at various times. Tajiks are therefore mainly Eastern Iranian in their ethnic makeup but speak a Persian dialect, which is a Western Iranian language, likely adopting the language in the 7th century AD following the Islamic conquest of Persia, when the prestigious Persian language consequently spread further east leading to the gradual extinction of the Bactrian and Sogdian languages.[26][27] The Tajiks and their ancestors have inhabited Northern Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and other parts of Central Asia continuously for many millennia.[28] The culture of the Tajiks is predominantly Persianate but with strong elements from other cultures of Central Asia, such as Turkic and heavily infused with Islamic traditions.

History

The Tajiks are an Iranian people, speaking a variety of Persian, concentrated in the Oxus Basin, the Farḡāna valley (Tajikistan and parts of Uzbekistan) and on both banks of the upper Oxus, i.e., the Pamir Mountains (Mountain Badaḵšān, in Tajikistan) and northeastern Afghanistan (Badaḵšān).[21] Historically, the ancient Tajiks were chiefly agriculturalists before the Arab Conquest of Iran.[29] While agriculture remained a stronghold, the Islamization of Iran also resulted in the rapid urbanization of historical Khorasan and Transoxiana that lasted until the devastating Mongolian invasion.[30] Several surviving ancient urban centers of the Tajik people include Samarkand, Bukhara, Khujand, and Termez.

Contemporary Tajiks are the descendants of ancient Eastern Iranian inhabitants of Central Asia, in particular, the Sogdians and the Bactrians.[24] Possibly are descendants from other groups, with an admixture of Western Iranian Persians and non-Iranian peoples.[24][31] The latter group may include Greeks who were known to have settled in the Tajikistan and Uzbekistan region following the conquests of Alexander the Great and some of them were referred to as Dayuan by Chinese chronicles.[32] According to Richard Nelson Frye, a leading historian of Iranian and Central Asian history, the Persian migration to Central Asia may be considered the beginning of the modern Tajik nation, and ethnic Persians, along with some elements of East-Iranian Bactrians and Sogdians, as the main ancestors of modern Tajiks.[33] In later works, Frye expands on the complexity of the historical origins of the Tajiks. In a 1996 publication, Frye explains that many "factors must be taken into account in explaining the evolution of the peoples whose remnants are the Tajiks in Central Asia" and that "the peoples of Central Asia, whether Iranian or Turkic speaking, have one culture, one religion, one set of social values and traditions with only language separating them."[34]

Regarding Tajiks, the Encyclopædia Britannica states:

The Tajiks are the direct descendants of the Iranian peoples whose continuous presence in Central Asia and northern Afghanistan is attested from the middle of the 1st millennium BC. The ancestors of the Tajiks constituted the core of the ancient population of Khwārezm (Khorezm) and Bactria, which formed part of Transoxania (Sogdiana). Over the course of time, the eastern Iranian dialect that was used by the ancient Tajiks eventually gave way to Farsi, a western dialect spoken in Iran and Afghanistan.[35]

The geographical division between the eastern and western Iranians is often considered historically and currently to be the desert Dasht-e Kavir, situated in the center of the Iranian plateau.[36]

Modern history

During the Soviet–Afghan War, the Tajik-dominated Jamiat-e Islami founded by Burhanuddin Rabbani resisted the Soviet Army and the communist Afghan government. Tajik commander, Ahmad Shah Massoud, successfully repelled nine Soviet campaigns from taking Panjshir Valley and earned the nickname "Lion of Panjshir" (شیر پنجشیر).

Etymology

According to John Perry (Encyclopaedia Iranica):[21]

The most plausible and generally accepted origin of the word is Middle Persian tāzīk 'Arab' (cf. New Persian tāzi), or an Iranian (Sogdian or Parthian) cognate word. The Muslim armies that invaded Transoxiana early in the eighth century, conquering the Sogdian principalities and clashing with the Qarluq Turks (see Bregel, Atlas, Maps 8–10) consisted not only of Arabs, but also of Persian converts from Fārs and the central Zagros region (Bartol'd [Barthold], "Tadžiki," pp. 455–57). Hence the Turks of Central Asia adopted a variant of the Iranian word, täžik, to designate their Muslim adversaries in general. For example, the rulers of the south Indian Chalukya dynasty and Rashtrakuta dynasty also referred to the Arabs as "Tajika" in the 8th and 9th century.[37][38] By the eleventh century (Yusof Ḵāṣṣ-ḥājeb, Qutadḡu bilig, lines 280, 282, 3265), the Qarakhanid Turks applied this term more specifically to the Persian Muslims in the Oxus basin and Khorasan, who were variously the Turks' rivals, models, overlords (under the Samanid Dynasty), and subjects (from Ghaznavid times on). Persian writers of the Ghaznavid, Seljuq and Atābak periods (ca. 1000–1260) adopted the term and extended its use to cover Persians in the rest of Greater Iran, now under Turkish rule, as early as the poet ʿOnṣori, ca. 1025 (Dabirsiāqi, pp. 3377, 3408). Iranians soon accepted it as an ethnonym, as is shown by a Persian court official's referring to mā tāzikān "we Tajiks" (Bayhaqi, ed. Fayyāz, p. 594). The distinction between Turk and Tajik became stereotyped to express the symbiosis and rivalry of the (ideally) nomadic military executive and the urban civil bureaucracy (Niẓām al-Molk: tāzik, pp. 146, 178–79; Fragner, "Tādjīk. 2" in EI2 10, p. 63).

The word also occurs in the 8th-century Tonyukuk inscriptions as tözik, used for a local Arab tribe in the Tashkent area.[39] These Arabs were said to be from the Taz tribe, which is still found in Yemen. In the 7th-century, the Taz began to Islamize the region of Transoxiana in Central Asia.[40]

According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, however, the oldest known usage of the word Tajik as a reference to Persians in Persian literature can be found in the writings of the famous Persian poet and Islamic scholar Jalal ad-Din Rumi.[41] The 15th-century Turkic-speaking poet Mīr Alī Šer Navā'ī who lived in the Timurid empire also used Tajik as a reference to Persians.[42]

Location

The Tajiks are the principal ethnic group in most of Tajikistan, as well as in northern and western Afghanistan, though there are more Tajiks in Afghanistan than in Tajikistan. Tajiks are a substantial minority in Uzbekistan, as well as in overseas communities. Historically, the ancestors of the Tajiks lived in a larger territory in Central Asia than now.

Tajikistan

Tajiks make up around 84.3% of the population of Tajikistan.[43] This number includes speakers of the Pamiri languages, including Wakhi and Shughni, and the Yaghnobi people who in the past were considered by the government of the Soviet Union nationalities separate from the Tajiks. In the 1926 and 1937 Soviet censuses, the Yaghnobis and Pamiri language speakers were counted as separate nationalities. After 1937, these groups were required to register as Tajiks.[17]

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, a "Tajik", is typically defined as any primarily Dari-speaking Sunni Muslim who refer to themselves by the region, province, city, town, or village that they are from;[44] such as Badakhshi, Baghlani, Mazari, Panjsheri, Kabuli, Herati, Kohistani, etc.[44][45][46] Although in the past, some non-Pashto speaking tribes were identified as Tajik, for example, the Furmuli.[47][48] By this definition, according to the World Factbook, Tajiks make up about 25–27% of Afghanistan's population,[49][50] but according to other sources, they form 37–39% of the population.[51] Other sources however, for example the Encyclopædia Britannica, state that they constitute about 12–20% of the population,[52][53] which is mostly excluding Persianized ethnic groups like some Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Qizilbash, Aimaqs etc. who, especially in large urban areas like Kabul or Herat, assimiliated into the respective local culture.[54][55][56] Tajiks (or Farsiwans respectively) are predominant in four of the largest cities in Afghanistan (Kabul, Mazar-e Sharif, Herat, and Ghazni) and make up the qualified majority in the northern and western provinces of Badakhshan, Panjshir and Balkh, while making up significant portions of the population in Takhar, Kabul, Parwan, Kapisa, Baghlan, Badghis and Herat. Despite not being Tajik, the westernmost Indo-Aryan Pashayi people of northeastern Afghanistan have deliberately been listed as Tajik by census takers and government agents. This is a result of the census takers being Tajik themselves, wanting to increase their own numbers for “consequent benefits”. Although, Pashayi-speaking Nizari Isma’ilis refer to themselves as Tajik.[57]

Uzbekistan

In Uzbekistan, the Tajiks are the largest part of the population of the ancient cities of Bukhara and Samarkand, and are found in large numbers in the Surxondaryo Region in the south and along Uzbekistan's eastern border with Tajikistan. According to official statistics (2000), Surxondaryo Region accounts for 20.4% of all Tajiks in Uzbekistan, with another 34.3% in Samarqand and Bukhara regions.[58] Official statistics in Uzbekistan state that the Tajik community accounts for 5% of the nation's population.[59] However, these numbers do not include ethnic Tajiks who, for a variety of reasons, choose to identify themselves as Uzbeks in population census forms.[60] During the Soviet "Uzbekization" supervised by Sharof Rashidov, the head of the Uzbek Communist Party, Tajiks had to choose either stay in Uzbekistan and get registered as Uzbek in their passports or leave the republic for Tajikistan, which is mountainous and less agricultural.[61] It is only in the last population census (1989) that the nationality could be reported not according to the passport, but freely declared based on the respondent's ethnic self-identification.[62] This had the effect of increasing the Tajik population in Uzbekistan from 3.9% in 1979 to 4.7% in 1989. Some scholars estimate that Tajiks may make up 35% of Uzbekistan's population, and believe that just like Afghanistan, there are more Tajiks in Uzbekistan than in Tajikistan.[63]

China

Chinese Tajiks or Mountain Tajiks in China (Sarikoli: [tudʒik], Tujik; Chinese: 塔吉克族; pinyin: Tǎjíkè Zú), including Sarikolis (majority) and Wakhis (minority) in China, are the Pamiri ethnic group that lives in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwestern China. They are one of the 56 nationalities officially recognized by the government of the People's Republic of China.

Kazakhstan

According to the 1999 population census, there were 26,000 Tajiks in Kazakhstan (0.17% of the total population), about the same number as in the 1989 census.

Kyrgyzstan

According to official statistics, there were about 47,500 Tajiks in Kyrgyzstan in 2007 (0.9% of the total population), up from 42,600 in the 1999 census and 33,500 in the 1989 census.

Turkmenistan

According to the last Soviet census in 1989,[64] there were 3,149 Tajiks in Turkmenistan, or less than 0.1% of the total population of 3.5 million at that time. The first population census of independent Turkmenistan conducted in 1995 showed 3,103 Tajiks in a population of 4.4 million (0.07%), most of them (1,922) concentrated in the eastern provinces of Lebap and Mary adjoining the borders with Afghanistan and Uzbekistan.[65]

Russia

The population of Tajiks in Russia was about 350,236 according to the 2021 census,[66] up from 38,000 in the last Soviet census of 1989.[67] Most Tajiks came to Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, often as guest workers in places like Moscow and Saint Petersburg or federal subjects near the Kazakhstan border.[68] There are currently estimated to be over one million Tajik guest workers living in Russia, with their remittances accounting for as much as half of Tajikistan's economy.[69]

Pakistan

There are an estimated 220,000 Tajiks in Pakistan as of 2012, mainly refugees from Afghanistan.[70] During the 1990s, as a result of the Tajikistan Civil War, between 700 and 1,200 Tajiks arrived in Pakistan, mainly as students, the children of Tajik refugees in Afghanistan. In 2002, around 300 requested to return home and were repatriated back to Tajikistan with the help of the IOM, UNHCR and the two countries' authorities.[71]

United States

80,414 Tajiks live in the United States.[72]

Genetics

A 2014 study of the maternal haplogroups of Tajiks from Tajikistan revealed substantial admixture of West Eurasian and East Eurasian lineages, and also the presence of minor South Asian and North African lineages, as well.[73] Another study reports that "the Tajik mtDNA pool gene pool harbors nearly equal proportions of eastern Eurasian and western Eurasian haplotypes."[74]

West Eurasian maternal lineages included haplogroups H, J, K, T, I, W and U.[75] East Eurasian lineages included haplogroups M, C, Z, D, G, A, Y and B.[76] South Asian lineages detected in this study included haplogroups M and R.[77] One lineage in the Tajik sample was assigned to the North African maternal haplogroup X2j.[78]

The dominant paternal haplogroup among modern Tajiks is the Haplogroup R1a Y-DNA. ~45% of Tajik men share R1a (M17), ~18% J (M172), ~8% R2 (M124), and ~8% C (M130 & M48). Tajiks of Panjikent score 68% R1a, Tajiks of Khojant score 64% R1a.[79] According to another genetic test, 63% of Tajik male samples from Tajikistan carry R1a.[80] This high frequency combined with low diversity of Tajik R1a reflects a strong founder effect.[81]

An autosomal DNA study by Guarino-Vignon et al. (2022), suggested that modern Tajiks show genetic continuity with ancient samples from Tajikistan and Turkmenistan. The genetic ancestry of Tajiks consists largely of a West-Eurasian component (~74%), an East Asian-related component (~18%), and a South Asian component (~8%). According to the authors, the South Asian affinity of Tajiks was previously unreported, although evidence for the presence of a deep South Asian ancestry was already found previously in other Central Asian samples (e.g. among modern Turkmens and historical Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex samples). Both historical and more recent geneflow (~1500 years ago) shaped the genetic makeup of Southern Central Asian populations, such as the Tajiks.[82] A follow-up study by Dai et al. (2022) estimated that the Tajiks derive between 11.6 and 18.6% ancestry from admixture with from an East-Eurasian steppe source represented by the Xiongnu, with the remainder of their ancestry being derived from Western Steppe Herders and BMAC components, as well as a small contribution from the early population associated with the Tarim mummies. The authors concluded that Tajiks "present patterns of genetic continuity of Central Asians since the Bronze Age".[83]

Culture

| Part of a series on |

| Tajiks |

|---|

| History and culture |

| Population |

Language

The language of the Tajiks is an eastern dialect of Persian, called Dari (derived from Darbārī, "[of/from the] royal courts", in the sense of "courtly language"), or also Parsi-e Darbari. In Tajikistan, where Cyrillic script is used, it is called the Tajiki language. In Afghanistan, unlike in Tajikistan, Tajiks continue to use the Perso-Arabic script, as well as in Iran. When the Soviet Union introduced the Latin script in 1928, and later the Cyrillic script, the Persian dialect of Tajikistan came to be disassociated from the Tajik language. Many Tajik authors have lamented this artificial separation of the Tajik language from its Iranian heritage.[84] One Tajik poem relates:

Once you said 'you are Iranian', then you said, 'you are Tajik' May he die separated from his roots, he who separated us.[85][84]

Since the 19th century, Tajiki has been strongly influenced by the Russian language and has incorporated many Russian language loan words.[86] It has also adopted fewer Arabic loan words than Iranian Persian while retaining vocabulary that has fallen out of use in the latter language.

Many Tajiks can read, speak or write in Russian, however the prestige and importance of Russian has declined since the fall of the Soviet Union and the exodus of Russians from Central Asia. Nevertheless, Russian fluency is still considered an vital skill for business and education.[87]

The dialects of modern Persian spoken throughout Greater Iran have a common origin. This is due to the fact that one of Greater Iran's historical cultural capitals, called Greater Khorasan, which included parts of modern Central Asia and much of Afghanistan and constitutes as the Tajik's ancestral homeland, played a key role in the development and propagation of Persian language and culture throughout much of Greater Iran after the Muslim conquest. Furthermore, early manuscripts of the historical Persian spoken in Mashhad during the development of Middle to New Persian show that their origins came from Sistan, in present-day Afghanistan.[21]

Religion

Various scholars have recorded the Zoroastrian, and Buddhist pre-Islamic heritage of the Tajik people. Early temples for fire worship have been found in Balkh and Bactria and excavations in present-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan show remnants of Zoroastrian fire temples.[88]

Today, however, the great majority of Tajiks follow Sunni Islam, although small Twelver and Ismaili Shia minorities also exist in scattered pockets. Areas with large numbers of Shias include Herat, Badakhshan provinces in Afghanistan, the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province in Tajikistan, and Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County in China. Some of the famous Islamic scholars were from either modern or historical East-Iranian regions lying in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan and therefore can arguably be viewed as Tajiks. They include Abu Hanifa,[21] Imam Bukhari, Tirmidhi, Abu Dawood, Nasir Khusraw and many others.

According to a 2009 U.S. State Department release, the population of Tajikistan is 98% Muslim, (approximately 85% Sunni and 5% Shia).[89] In Afghanistan, the great number of Tajiks adhere to Sunni Islam. A small number of Tajiks may follow Twelver Shia Islam; the Farsiwan are one such group.[90] The community of Bukharian Jews in Central Asia speak a dialect of Persian. The Bukharian Jewish community in Uzbekistan is the largest remaining community of Central Asian Jews and resides primarily in Bukhara and Samarkand, while the Bukharaian Jews of Tajikistan live in Dushanbe and number only a few hundred.[91] From the 1970s to the 1990s the majority of these Tajik-speaking Jews emigrated to the United States and to Israel in accordance with Aliyah. Recently, the Protestant community of Tajiks descent has experienced significant growth, a 2015 study estimates some 2,600 Muslim Tajik converted to Christianity.[92]

Tajikistan marked 2009 as the year to commemorate the Tajik Sunni Muslim jurist Abu Hanifa, whose ancestry hailed from Parwan Province of Afghanistan, as the nation hosted an international symposium that drew scientific and religious leaders.[93] The construction of one of the largest mosques in the world, funded by Qatar, was announced in October 2009. The mosque is planned to be built in Dushanbe and construction is said to be completed by 2014.[94]

Recent developments

Cultural revival

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Civil War in Afghanistan both gave rise to a resurgence in Tajik nationalism across the region, including a trial to revert to the Perso-Arabic script in Tajikistan.[95][21][96] Furthermore, Tajikistan in particular has been a focal point for this movement, and the government there has made a conscious effort to revive the legacy of the Samanid empire, the first Tajik-dominated state in the region after the Arab advance. For instance, the President of Tajikistan, Emomalii Rahmon, dropped the Russian suffix "-ov" from his surname and directed others to adopt Tajik names when registering births.[97] According to a government announcement in October 2009, approximately 4,000 Tajik nationals have dropped "ov" and "ev" from their surnames since the start of the year.[98]

In September 2009, the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan proposed a draft law to have the nation's language referred to as "Tajiki-Farsi" rather than "Tajik." The proposal drew criticism from Russian media since the bill sought to remove the Russian language as Tajikistan's inter-ethnic lingua franca.[99] In 1989, the original name of the language (Farsi) had been added to its official name in brackets, though Rahmon's government renamed the language to simply "Tajiki" in 1994.[99] On 6 October 2009, Tajikistan adopted the law that removes Russian as the lingua franca and mandated Tajik as the language to be used in official documents and education, with an exception for members Tajikistan's ethnic minority groups, who would be permitted to receive an education in the language of their choosing.[100]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "Afghanistan Population 2024 (Live)".

- ^ Mobasher, Mohammad Bashir. "Political Laws and Ethnic Accommodation: Why Cross-Ethnic Coalitions Have Failed to Institutionalize in Afghanistan" (PDF). digital.lib.washington.edu. University of Washington.

- ^ "Dissemination of the Republic of Tajikistan Population and Housing Census data 2020" (PDF). unece.org.

- ^ "Tajikistan Population 2024 (Live)".

- ^ "Permanent population by national and / Or ethnic group, urban / Rural place of residence".

- ^ Karl Cordell, "Ethnicity and Democratisation in the New Europe", Routledge, 1998. p. 201: "Consequently, the number of citizens who regard themselves as Tajiks is difficult to determine. Tajikis within and outside of the republic, Samarkand State University (SamGU) academic and international commentators suggest that there may be between six and seven million Tajiks in Uzbekistan, constituting 30% of the republic's 22 million population, rather than the official figure of 4.7%(Foltz 1996;213; Carlisle 1995:88).

- ^ Lena Jonson (1976) "Tajikistan in the New Central Asia", I.B.Tauris, p. 108: "According to official Uzbek statistics there are slightly over 1 million Tajiks in Uzbekistan or about 3% of the population. The unofficial figure is over 6 million Tajiks. They are concentrated in the Sukhandarya, Samarqand and Bukhara regions."

- ^ "Оценка численности постоянного населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ "Total population by nationality (assessment at the beginning of the year, people)". Bureau of Statistics of Kyrgyzstan. 2021. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "US demographic census". Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2008. Of this number, approximately 65% are Tajiks according to a group of American researchers (Barbara Robson, Juliene Lipson, Farid Younos, Mariam Mehdi). Robson, Barbara and Lipson, Juliene (2002) "Chapter 5(B)- The People: The Tajiks and Other Dari-Speaking Groups" Archived 27 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Afghans – their history and culture Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, Washington, D.C., OCLC 56081073 Archived 13 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам". stat.gov.kz. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ "塔吉克族". www.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ State statistics committee of Ukraine – National composition of population, 2001 census Archived 23 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (Ukrainian)

- ^ "Все новости". Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ "Tajikistan". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- ^ a b C.E. Bosworth; B.G. Fragner (1999). "TĀDJĪK". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ^ a b Suny, Ronald Grigor (2006). "History and Foreign Policy: From Constructed Identities to "Ancient Hatreds" East of the Caspian". In Shaffer, Brenda (ed.). The Limits of Culture: Islam and Foreign Policy. MIT Press. pp. 100–110. ISBN 0-262-69321-6.

- ^ Arlund, Pamela S. (2006). An Acoustic, Historical, And Developmental Analysis of Sarikol Tajik Diphthongs. PhD Dissertation. The University of Texas at Arlington. p. 191. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Felmy, Sabine (1996). The voice of the nightingale: a personal account of the Wakhi culture in Hunza. Karachi: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-19-577599-6. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ Minahan, James B. (10 February 2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ a b c d e f g Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ B. A. Litvinsky, Ahmad Hasan Dani (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Age of Achievement, A.D. 750 to the end of the 15th-century. Excerpt: "...they were the basis for the emergence and gradual consolidation of what became an Eastern Persian-Tajik ethnic identity." pp. 101. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231032110.

- ^ M. Longworth Dames; G. Morgenstierne & R. Ghirshman (1999). "AFGHĀNISTĀN". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ^ a b c Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan : country studies Archived 20 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, page 206

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2019). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East. I.B.Tauris. pp. 36–39. ISBN 978-1-7883-1652-1.

- ^ Paul Bergne (15 June 2007). The Birth of Tajikistan: National Identity and the Origins of the Republic. I.B.Tauris. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-84511-283-7.

- ^ Josef W. Meri; Jere L. Bacharach (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. Taylor & Francis. pp. 829–. ISBN 978-0-415-96692-4. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2024.

- ^ [1] Archived 21 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Zerjal, Tatiana; Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–482. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- ^ Wink, André (2002). Al-Hind: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th–13th centuries. BRILL. ISBN 0391041746. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2018 – via google.nl.

- ^ Foltz 2023, p. 33-60.

- ^ Watson, Burton(1993). Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian. Translated by Burton Watson. Han Dynasty II (Revised Edition), pp. 244–245. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08166-9; ISBN 0-231-08167-7 (pbk)

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye, "Persien: bis zum Einbruch des Islam" (original English title: "The Heritage of Persia"), German version, tr. by Paul Baudisch, Kindler Verlag AG, Zürich 1964, pp. 485–498

- ^ Frye, Richard Nelson (1996). The heritage of Central Asia from antiquity to the Turkish expansion. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 1-55876-110-1. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ^ [2] Archived 21 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Soper, J.D.; Bodrogligeti, A.J.E. (1996). Loan Syntax in Turkic and Iranian. Eurasian language archives. Eurolingua. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-931922-58-9. Retrieved 1 November 2023. "Western languages were located in the western portion of the Iranian plateau, separated by the Dasht - e Kavir and Dasht - e Lūt deserts from the Eastern Iranian dialects."

- ^ Political History of the Chālukyas of Badami by Durga Prasad Dikshit p.192

- ^ The First Spring: The Golden Age of India by Abraham Eraly p.91

- ^ Lawrence Krader (1971). Peoples of Central Asia. Indiana University. p. 54.

- ^ Jean-Charles Blanc (1976). L'Afghanistan et ses populations (in French). Éditions Complexe. p. 80.

- ^ C.E. Bosworth/B.G. Fragner, "Tādjīk", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition: "... In Islamic usage, [Tādjīk] eventually came to designate the Persians, as opposed to Turks [...] the oldest citation for it which Schraeder could find was in verses of Djalāl al-Dīn Rūmī ..."

- ^ Ali Shir Nava'i Muhakamat al-lughatain tr. & ed. Robert Devereaux (Leiden: Brill) 1966 p6

- ^ "Tajikistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 5 May 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ a b [3], p. 26

- ^ "Ethnic Identity and Genealogies - Program for Culture and Conflict Studies - Naval Postgraduate School".

- ^ Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress (1997). "Afghanistan: Tajik". Country Studies Series. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ Bellew, Henry Walter (1891) An inquiry into the ethnography of Afghanistan The Oriental Institute, Woking, Butler & Tanner, Frome, United Kingdom, page 126, OCLC 182913077

- ^ Markham, C. R. (January 1879) "The Mountain Passes on the Afghan Frontier of British India" Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography (New Monthly Series) 1(1): pp. 38–62, p.48

- ^ "Population of Afghanistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ Country Factfiles. — Afghanistan, page 153. // Atlas. Fourth Edition. Editors: Ben Hoare, Margaret Parrish. Publisher: Jonathan Metcalf. First published in Great Britain in 2001 by Dorling Kindersley Limited. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2010, 432 pages. ISBN 9781405350396 "Population: 28.1 million

Religions: Sunni Muslim 84%, Shi'a Muslim 15%, other 1%

Ethnic Mix: Pashtun 38%, Tajik 25%, Hazara 19%, Uzbek, Turkmen, other 18%" - ^ "ABC NEWS/BBC/ARD poll – Afghanistan: Where Things Stand" (PDF). Kabul, Afghanistan: ABC News. pp. 38–40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ Maley, William, ed. Fundamentalism reborn?: Afghanistan and the Taliban, p. 170. NYU Press, 1998.

- ^ "Tajik". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

There were about 5,000,000 in Afghanistan, where they constituted about one-fifth of the population.

- ^ D, Hamid Hadi M. (24 March 2016). Afghanistan's Experiences: The History of the Most Horrifying Events Involving Politics, Religion, and Terrorism. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-5049-8614-4.

- ^ "Afghanistan - Qizilbash".

- ^ Fazel, S. M. (2017). Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi'a Minority (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University), p. 153.

- ^ Lehr, Rachel (2014). A Descriptive Grammar of Pashai: The Language and Speech Community of Darrai Nur (PDF). University of Chicago, Division of the Humanities, Department of Linguistics. ISBN 978-1-321-22417-7.

- ^ Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan Archived 6 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Part 1: Ethnic minorities, Open Society Institute, table with number of Tajiks by province (in Russian).

- ^ "Uzbekistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 6 May 2010. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (23 February 2000). "Uzbekistan". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 1999. U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rahim Masov, The History of the Clumsy Delimitation, Irfon Publ. House, Dushanbe, 1991 (in Russian). English translation: The History of a National Catastrophe, transl. Iraj Bashiri, 1996.

- ^ Ethnic Atlas of Uzbekistan Archived 6 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Part 1: Ethnic minorities, Open Society Institute, p. 195 (in Russian).

- ^ Svante E. Cornell, "Uzbekistan: A Regional Player in Eurasian Geopolitics?" Archived 5 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, European Security, vol. 20, no. 2, Summer 2000.

- ^ "Демоскоп Weekly – Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей". Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ Population census of Turkmenistan 1995, Vol. 1, State Statistical Committee of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat, 1996, pp. 75–100.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "2002 Russian census". Perepis2002.ru. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ "4. НАСЕЛЕНИЕ ПО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОСТИ И ВЛАДЕНИЮ РУССКИМ ЯЗЫКОМ ПО СУБЪЕКТАМ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ". gks.ru. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ^ Foltz 2023, p. 208.

- ^ The ethnic composition of the 1.7 million registered Afghan refugees living in Pakistan are believed to be 85% Pashtun and 15% Tajik, Uzbek and others."2012 UNHCR country operations profile – Pakistan". Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (1 October 2002). "Long-time Tajik refugees return home from Pakistan". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results".

- ^ Ovchinnikov, Igor V.; Malek, Mathew J.; Drees, Kenneth; Kholina, Olga I. (2014). "Mitochondrial DNA variation in Tajiks living in Tajikistan". Legal Medicine. 16 (6): 390–395. doi:10.1016/j.legalmed.2014.07.009. ISSN 1344-6223. PMID 25155918. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 17 January 2023. "The Tajik mtDNA pool was characterized by substantial admixture of western and eastern Eurasian haplogroups, 62.6% and 26.4% sequences, respectively. It also contained 9.9% of South Asian and 1.1% of African haplotypes."

- ^ Irwin, Jodi A. (6 February 2010). "The mtDNA composition of Uzbekistan: a microcosm of Central Asian patterns". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 124 (3). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 195–204. doi:10.1007/s00414-009-0406-z. ISSN 0937-9827. PMID 20140442. S2CID 2759130. "The Tajik mtDNA gene pool harbors nearly equal proportions of eastern Eurasian and western Eurasian haplotypes"...."The genetic features of other ethnic populations likely also reflect their documented demographic histories. For instance, the small mtDNA distance between the Tajik and Uzbek populations suggests a recent shared history. Tajiks and Uzbeks were only formally differentiated in 1929 when the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic was established, and up to 40% of the current Uzbek population is of Tajik ancestry (Library of Congress Federal Research Division Country Profile: Uzbekistan Feb 2007)."

- ^ Ovchinnikov et al. 2014, p. 392: "The western Eurasian component is represented by haplo- groups HV/, HV0, H, J, K, T, and U of the macrohaplogroup R, and haplogroups I and W of the macrohaplogroup N [22]."

- ^ Ovchinnikov et al. 2014, p. 392: "The eastern Eurasian component is represented by haplogroups M8, M10, C, Z, D, G of the macrohaplogroup M, haplogroups A and Y1 of the macrohaplogroup N, and haplogroup B of the macrohaplogroup R [22]."

- ^ Ovchinnikov et al. 2014, p. 392: "The south Asian component is comprised of nine mtDNA sequences (9.9%) belonging to the macrohaplogroups M and R [22]. Two sequences were assigned to main branches of M including M3a1 (1.1%) and M30 (1.1%). Macrohaplogroup R was represented by six mtDNA sequences (6.6%) belonging to R0a (1 sample), R1 (2 samples), R2 (1 sample), and R5a (2 samples). One Tajik mtDNA sequence (1.1%) belonged to aforementioned U2b2, a south Asian autochthonous subhaplogroup of the macrohaplogroup R [25]."

- ^ Ovchinnikov et al. 2014, p. 392: "One Tajik mtDNA sequence (1.1%) was assigned to subhaplogroup X2j. X2j is considered to be of North African origin [23]."

- ^ Wells, RS; Yuldasheva, N; Ruzibakiev, R; et al. (August 2001). "The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (18): 10244–9. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- ^ Zerjal, Tatiana; Wells, R. Spencer; Yuldasheva, Nadira; Ruzibakiev, Ruslan; Tyler-Smith, Chris (September 2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–482. doi:10.1086/342096. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- ^ Zerjal, T; Wells, RS; Yuldasheva, N; Ruzibakiev, R; Tyler-Smith, C (September 2002). "A Genetic Landscape Reshaped by Recent Events: Y-Chromosomal Insights into Central Asia". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (3): 466–82. doi:10.1086/342096. PMC 419996. PMID 12145751.

- ^ Guarino-Vignon, Perle; Marchi, Nina; Bendezu-Sarmiento, Julio; Heyer, Evelyne; Bon, Céline (14 January 2022). "Genetic continuity of Indo-Iranian speakers since the Iron Age in southern Central Asia". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 733. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12..733G. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04144-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8760286. PMID 35031610.

- ^ Dai et al. 2022 (25 August 2022). "The Genetic Echo of the Tarim Mummies in Modern Central Asians". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 39 (9). doi:10.1093/molbev/msac179. PMC 9469894. PMID 36006373. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) "The Historical Era gene flow derived from the Eastern Steppe with the representative of Mongolia_Xiongnu_o1 made a more substantial contribution to Kyrgyz and other Turkic-speaking populations (i.e., Kazakh, Uyghur, Turkmen, and Uzbek; 34.9–55.2%) higher than that to the Tajik populations (11.6–18.6%; fig. 4A), suggesting Tajiks suffer fewer impacts of the recent admixtures (Martínez-Cruz et al. 2011). Consequently, the Tajik populations generally present patterns of genetic continuity of Central Asians since the Bronze Age. Our results are consistent with linguistic and genetic evidence that the spreading of Indo-European speakers into Central Asia was earlier than the expansion of Turkic speakers (Kuz′mina and Mallory 2007; Yunusbayev et al. 2015)." - ^ a b Foltz 2023, p. 103.

- ^ Moḥammad Reẓa Shafi‘ī-Kadkanī, ‘Borbad’s Khusravanis – First Iranian Songs’, in Iraj Bashiri (tr and ed), From the Hymns of Zarathustra to the Songs of Borbad, Dushanbe, 2003, p. 135.

- ^ Michael Knüppel. Turkic Loanwords in Persian Archived 27 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Abdullaev, K. (2018). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Historical Dictionaries of Asia, Oceania, and the Middle East. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ Lena Jonson, Tajikistan in the New Central Asia: Geopolitics, Great Power Rivalry and Radical Islam Archived 10 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine (International Library of Central Asia Studies), page 21

- ^ "Background Note: Tajikistan". State.gov. 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Shaikh, F. (1992). Islam and Islamic Groups: A Worldwide Reference Guide. Longman Law Series. Longman Group UK. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-582-09146-7. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ^ J. Sloame, "Bukharan Jews", Jewish Virtual Library, (LINK Archived 13 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11 (10): 1–19. Archived from the original on 13 March 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Today marks 18th year of Tajik independence and success". Todayszaman.com. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Daniel Bardsley (25 May 2010). "Qatar paying for giant mosque in Tajikistan". Thenational.ae. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Perry, John. "TAJIK ii. TAJIK PERSIAN". TAJIK II. TAJIK PERSIAN. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ^ Rubin, Barnett; Snyder, Jack (1 November 2002). Post-Soviet Political Order. Routledge. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-134-69758-8.

- ^ McDermott, Roger (25 April 2007). "Tajikistan restates its strategic partnership with Russia, while sending mixed signals". The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ^ "Some 4,000 Tajiks opt to use the traditional version of their names this year". Asiaplus.tj. 17 October 1962. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ a b "Tajik Islamic Party Seeks Tajiki-Farsi Designation". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ "Tajikistan Drops Russian As Official Language". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

Further reading

- Foltz, R. (2023). A History of the Tajiks: Iranians of the East. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7556-4967-9. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- Ghafurov, Bobojon (1991). Tajiks: Pre-ancient, ancient and medieval history. Dushanbe: Irfon.

- Dupree, Louis (1980). Afghanistan. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Jawad, Nassim (1992). Afghanistan: A Nation of Minorities. London: Minority Rights Group International. ISBN 0-946690-76-6.

- "The Sogdian Descendants in Mongol and post-Mongol Central Asia: The Tajiks and Sarts" (PDF). Joo Yup Lee. ACTA VIA SERICA Vol. 5, No. 1, June 2020: 187–198doi: 10.22679/avs.2020.5.1.007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

External links

Media related to Tajiks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tajiks at Wikimedia Commons- Tajiks at Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Tajik – The Ethnonym: Origins and Application at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Ethnic Tajik people

- Ethnic groups in Afghanistan

- Ethnic groups in Tajikistan

- Ethnic groups in Uzbekistan

- Iranian ethnic groups

- Ethnic groups divided by international borders

- Ethnic groups in Central Asia

- Ethnic groups in Russia

- Ethnic groups in Pakistan

- Ethnic groups in Malakand

- Ethnic groups in Kabul Province

- Ethnic groups in Parwan Province