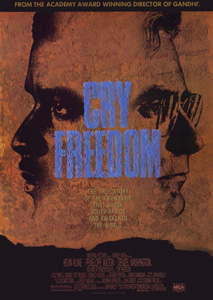

Cry Freedom

| Cry Freedom | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Richard Attenborough |

| Screenplay by | John Briley |

| Based on | Biko and Asking for Trouble by Donald Woods |

| Produced by | Richard Attenborough |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ronnie Taylor |

| Edited by | Lesley Walker |

| Music by | George Fenton Jonas Gwangwa |

Production company | Marble Arch Productions |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures (United States) United International Pictures (International) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 157 minutes |

| Country | |

| Languages | English Afrikaans Xhosa Zulu Sesotho |

| Budget | $29 million |

| Box office | $15 million (theatrical rentals)[2] |

Cry Freedom is a 1987 epic biographical drama film directed and produced by Richard Attenborough, set in late-1970s apartheid-era South Africa. The screenplay was written by John Briley based on a pair of books by journalist Donald Woods. The film centres on the real-life events involving South African activist Steve Biko and his friend Woods, who initially finds him too radical, and attempts to understand his way of life. Denzel Washington stars as Biko, while Kevin Kline portrays Woods. Penelope Wilton co-stars as Woods' wife Wendy. Cry Freedom delves into the ideas of discrimination, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence.

A joint collective effort to commit to the film's production was made by Universal Pictures and Marble Arch Productions and the film was primarily shot on location in Zimbabwe due to not being allowed to film in South Africa at the time of production. It was commercially distributed by Universal Pictures, opening in the United States on 6 November 1987. South African authorities unexpectedly allowed the film to be screened in cinemas without cuts or restrictions, despite the publication of Biko's writings being banned at the time of its release.[3]

The film was generally met with favourable reviews and earned theatrical rentals of $15 million worldwide. The film was nominated for multiple awards, including Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actor (for Washington), Best Original Score, and Best Original Song. It was nominated for seven BAFTA Awards, including Best Film and Best Direction, and won Best Sound.

Plot

[edit]Following a news story depicting the demolition of a slum in East London in the south-east of the Cape Province in South Africa, liberal white South African journalist Donald Woods seeks more information about the incident and ventures off to meet the anti-Apartheid black activist Steve Biko, a leading member of the Black Consciousness Movement. Biko has been officially banned by the government and is not permitted to leave his defined 'banning area' at King William's Town. Woods is opposed to Biko's banning, but remains critical of his political views. Biko invites Woods to visit a black township to see the impoverished conditions and to witness the effect of the Government-imposed restrictions, which make up the apartheid system. Woods begins to agree with Biko's desire for a South Africa where blacks have the same opportunities and freedoms as those enjoyed by the white population. As Woods comes to understand Biko's point of view, a friendship slowly develops between them.

After speaking at a gathering of black South Africans outside of his banishment zone, Biko is arrested and interrogated by the South African security forces (who have been tipped off by an informer). Following this, he is brought to court in order to explain his message directed toward the South African Government, which is white minority-controlled. After he speaks eloquently in court and advocates non-violence, the security officers who interrogated him visit his church and vandalise the property. Woods assures Biko that he will meet with a Government official to discuss the matter. Woods then meets with Jimmy Kruger (John Thaw), the South African Minister of Justice, in his house in Pretoria in an attempt to prevent further abuses. Minister Kruger first expresses discontent over their actions; however, Woods is later harassed at his home by security forces, who insinuate that their orders came directly from Kruger.

Later, Biko travels to Cape Town to speak at a student-run meeting. En route, security forces stop his car and arrest him asking him to say his name, and he said "Bantu Stephen Biko". He is held in harsh conditions and beaten, causing a severe brain injury. A doctor recommends consulting a nearby specialist in order to best treat his injuries, but the police refuse out of fear that he might escape. The security forces instead decide to take him to a police hospital in Pretoria, around 700 miles (1 200 km) away from Cape Town. He is thrown into the back of a prison van and driven on a bumpy road, aggravating his brain injury and resulting in his death.

Woods then works to expose the police's complicity in Biko's death. He attempts to expose photographs of Biko's body that contradict police reports that he died of a hunger strike, but he is prevented just before boarding a plane to leave and informed that he is now 'banned', therefore not able to leave the country. Woods and his family are targeted in a campaign of harassment by the security police, including bullets fired into the family home, vandalism, and the delivery of t-shirts with Biko's image that have been dusted with itching powder. He later decides to seek asylum in Britain in order to expose the corrupt and racist nature of the South African authorities. After a long trek, Woods is eventually able to escape to the Kingdom of Lesotho, disguised as a priest. His wife Wendy and their family later join him. With the aid of Australian journalist Bruce Haigh, the British High Commission in Maseru, and the Government of Lesotho, they are flown under United Nations passports and with one Lesotho official over South African territory, via Botswana, to London, where they were granted political asylum.

The film's epilogue displays a graphic detailing a long list of anti-apartheid activists (including Biko), who died under suspicious circumstances while imprisoned by the Government whilst the song Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika is sung.

Cast

[edit]- Denzel Washington as Steve Biko

- Kevin Kline as Donald Woods

- Penelope Wilton as Wendy Woods

- Alec McCowen as British Acting High Commissioner David Aubrey Scott

- Kevin McNally as Ken Robertson

- Ian Richardson as State Prosecutor

- John Thaw as Jimmy Kruger

- Timothy West as Captain De Wet

- Josette Simon as Dr. Mamphela Ramphele

- John Hargreaves as Bruce Haigh

- Miles Anderson as Lemick

- Zakes Mokae as Father Kani

- John Matshikiza as Mapetla

- Julian Glover as Don Card

- Philip Bretherton as Major Gert Boshoff

- Michael Turner as Judge W. G. Boshoff

- Paul Jerricho as Sergeant Louw

- Louis Mahoney as Lesotho Official

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

The premise of Cry Freedom is based on the true story of Steve Biko, the charismatic South African Black Consciousness Movement leader who attempts to bring awareness to the injustice of apartheid, and Donald Woods, the liberal white editor of the Daily Dispatch newspaper who struggles to do the same after Biko is murdered. In 1972, Biko was one of the founders of the Black People's Convention working on social upliftment projects around Durban.[4] The BPC brought together almost 70 different black consciousness groups and associations, such as the South African Student's Movement (SASM), which played a significant role in the 1976 uprisings, and the Black Workers Project, which supported black workers whose unions were not recognised under the apartheid regime.[4] Biko's political activities eventually drew the attention of the South African Government which often harassed, arrested, and detained him. These situations resulted in his being 'banned' in 1973.[5] The banning restricted Biko from talking to more than one person at a time, in an attempt to suppress the rising anti-apartheid political movement. Following a violation of his banning, Biko was arrested and later killed while in the custody of the South African Police (the SAP). The circumstances leading to Biko's death caused worldwide anger, as he became a martyr and symbol of black resistance.[4] As a result, the South African Government 'banned' a number of individuals (including Donald Woods) and organisations, especially those closely associated with Biko.[4] The United Nations Security Council responded swiftly to the killing by later imposing an arms embargo against South Africa.[4] After a period of routine harassment against his family by the authorities, as well as fearing for his life,[6] Woods fled the country after being placed under house arrest by the South African Government.[6] Woods later wrote a book in 1978 entitled Biko, exposing police complicity in his death.[5] That book, along with Woods's autobiography Asking For Trouble, both being published in the United Kingdom, became the basis for the film.[5]

Filming

[edit]Every exterior (outdoor) scene was filmed in Zimbabwe, as were roughly 70% of interior shots. The remaining interior shots were all filmed in England.[7] Principal filming took place primarily in Harare in Zimbabwe because of the tense political situation in South Africa at the time of shooting.[8]

The film includes a dramatised depiction of the Soweto uprising which occurred on 16 June 1976. Indiscriminate firing by police killed and injured hundreds of black African schoolchildren during a protest march.[5]

Music

[edit]The original motion picture soundtrack for Cry Freedom was released by MCA Records on 25 October 1990.[9] It features songs composed by veteran musicians George Fenton, Jonas Gwangwa and Thuli Dumakude. At Biko's funeral they sing the hymn "Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika". Jonathan Bates edited the film's music.[10]

A live version of Peter Gabriel's 1980 song "Biko" was released to promote the film; although the song was not on the film soundtrack, footage was used in its video.[11]

The title song was nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Song Written for Visual Media at the 31st Annual Grammy Awards, but lost to "Two Hearts" from Buster, performed by Phil Collins.

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Among mainstream critics in the U.S., the film received mostly positive reviews. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 74% of 27 sampled critics gave the film a positive review, with an average score of 6.5 out of 10.[12] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 59 out of 100 based on 15 critic reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews."[13] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[14]

| "It can be admired for its sheer scale. Most of all, it can be appreciated for what it tries to communicate about heroism, loyalty and leadership, about the horrors of apartheid, about the martyrdom of a rare man." |

| —Janet Maslin, writing in The New York Times[15] |

Rita Kempley, writing in The Washington Post, said actor Washington gave a "zealous, Oscar-caliber performance as this African messiah, who was recognized as one of South Africa's major political voices when he was only 25."[16] Also writing for The Washington Post, Desson Howe thought the film "could have reached further" and felt the story centring on Woods's character was "its major flaw". He saw director Attenborough's aims as "more academic and political than dramatic". Overall, he expressed his disappointment by exclaiming, "In a country busier than Chile with oppression, violence and subjugation, the story of Woods' slow awakening is certainly not the most exciting, or revealing."[17]

Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times offered a mixed review calling it a "sincere and valuable movie" while also exclaiming, "Interesting things were happening, the performances were good and it is always absorbing to see how other people live." But on a negative front, he noted how the film "promises to be an honest account of the turmoil in South Africa but turns into a routine cliff-hanger about the editor's flight across the border. It's sort of a liberal yuppie version of that Disney movie where the brave East German family builds a hot-air balloon and floats to freedom."[18]

Janet Maslin writing in The New York Times saw the film as "bewildering at some points and ineffectual at others" but pointed out that "it isn't dull. Its frankly grandiose style is transporting in its way, as is the story itself, even in this watered-down form." She also complimented the African scenery, noting that "Cry Freedom can also be admired for Ronnie Taylor's picturesque cinematography".[15] The Variety Staff felt Washington did "a remarkable job of transforming himself into the articulte [sic] and mesmerizing black nationalist leader, whose refusal to keep silent led to his death in police custody and a subsequent coverup." On Kline's performance, they noticed how his "low-key screen presence serves him well in his portrayal of the strong-willed but even-tempered journalist."[19] Film critic Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film a thumbs up review calling it "fresh" and a "solid adventure" while commenting "its images do remain in the mind ... I admire this film very much." He thought both Washington's and Kline's portrayals were "effective" and "quite good".[20] Similarly, Michael Price writing in the Fort Worth Press viewed Cry Freedom as often "harrowing and naturalistic but ultimately self-important in its indictment of police-state politics."[21]

| "Attenborough tries to rally with Biko flashbacks and a depiction of the Soweto massacre. But the 1976 slaughter of black schoolchildren is chronologically and dramatically out of place. And the flashbacks only remind you of whom you'd rather be watching." |

| —Desson Howe, writing for The Washington Post[17] |

Mark Salisbury of Time Out wrote of the lead acting to be "excellent" and the crowd scenes "astonishing", while equally observing how the climax was "truly nerve-wracking". He called it "an implacable work of authority and compassion, Cry Freedom is political cinema at its best."[22] James Sanford, however, writing for the Kalamazoo Gazette, did not appreciate the film's qualities, calling it "a Hollywood whitewashing of a potentially explosive story."[23] Rating the film with 3 Stars, critic Leonard Maltin wrote that the film was a "sweeping and compassionate film". He did, however, note that the film "loses momentum as it spends too much time on Kline and his family's escape from South Africa". But in positive followup, he pointed out that it "cannily injects flashbacks of Biko to steer it back on course."[24]

John Simon of the National Review called Cry Freedom "grandiosely inept".[25]

In 2013, the movie was one of several discussed by David Sirota in Salon in an article concerning white saviour narratives in film.[26]

Accolades

[edit]Box-office

[edit]The film opened on 6 November 1987 in limited release in 27 cinemas throughout the U.S. During its opening weekend, the film opened in 19th place and grossed $318,723.[36] The film was originally set to debut on November 20, 1987, but it was delayed to January–February 1988 as proposed.[37] The film expanded to 479 screens for the weekend of 19–21 February[38] and went on to gross $5,899,797 in the United States and Canada,[39] generating theatrical rentals of $2 million.[2] Internationally, the film earned rentals of $13 million, for a worldwide total of $15 million.[2]

It earned £3,313,150 in the UK.[40]

Home media

[edit]Following its cinematic release in the late 1980s, the film was released to television in a syndicated two-night broadcast. Extra footage was added to the film to fill in the block of time. The film was later released in VHS video format on 5 May 1998.[41] The Region 1 widescreen edition of the film was released on DVD in the United States on 23 February 1999. Special features for the DVD include: production notes, cast and filmmakers' biographies, film highlights, web links, and the theatrical cinematic.[42] It was released on Blu-ray Disc by Umbrella Entertainment in Australia in 2019, and in 2020 by Kino Lorber in the US. It is also available in other media formats such as video on demand.[43]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Biko, Steve (1979). Steve Biko: Black Consciousness in South Africa; Biko's Last Public Statement and Political Testament. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-72739-4.

- Biko, Steve (2002). I Write What I Like: Selected Writings. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-04897-0.

- Clarke, Anthony J.; Fiddes, Paul S., eds. (2005). Flickering Images: Theology and Film in Dialogue. Regent's Study Guides. Vol. 12. Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys Publishing. ISBN 1-57312-458-3.

- Goodwin, June (1995). Heart of Whiteness: Afrikaners Face Black Rule In the New South Africa. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-81365-3.

- Harlan, Judith (2000). Mamphela Ramphele. The Feminist Press at CUNY. ISBN 978-1-55861-226-6.

- Juckes, Tim (1995). Opposition in South Africa: The Leadership of Z. K. Matthews, Nelson Mandela, and Stephen Biko. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-94811-5.

- Magaziner, Daniel (2010). The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968–1977. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1918-2.

- Malan, Rian (2000). My Traitor's Heart: A South African Exile Returns to Face His Country, His Tribe, and His Conscience. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3684-8.

- Omand, Roger (1989). Steve Biko and Apartheid (People & Issues). Hamish Hamilton Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-12640-0.

- Paul, Samuel (2009). The Ubuntu God: Deconstructing a South African Narrative of Oppression. Pickwick Publications. ISBN 978-1-55635-510-3.

- Pityana, Barney (1992). Bounds of Possibility: The Legacy of Steve Biko & Black Consciousness. D. Philip. ISBN 978-1-85649-047-4.

- Price, Linda (1992). Steve Biko (They Fought for Freedom). Maskew Miller Longman. ISBN 978-0-636-01660-6.

- Tutu, Desmond (1996). The Rainbow People of God. Image. ISBN 978-0-385-48374-2.

- Van Wyk, Chris (2007). We Write What We Like: Celebrating Steve Biko. Wits University Press. ISBN 978-1-86814-464-8.

- Wa Thingo, Ngugi (2009). Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance. Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00946-6.

- Wiwa, Ken (2001). In the Shadow of a Saint: A Son's Journey to Understand His Father's Legacy. Steerforth. ISBN 978-1-58642-025-3.

- Woods, Donald (2004). Rainbow Nation Revisited: South Africa's Decade of Democracy. Andre Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-233-00052-7.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Cry Freedom (1987)". BFI Collections. Retrieved 18 July 2024.

- ^ a b c "Foreign Vs. Domestic Rentals". Variety. 11 January 1989. p. 24.

- ^ Battersby, John D. (28 November 1987). "Pretoria Censors to Let 'Cry Freedom' Be Seen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ a b c d e "Stephen Bantu (Steve) Biko". About.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Stephen Bantu Biko". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ a b 1978: Newspaper editor flees South Africa. BBC. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/1987/11/06/movies/review-film-cry-freedom.html

- ^ Hill, Geoff (2005) [2003]. The Battle for Zimbabwe: The Final Countdown. Johannesburg: Struik Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-86872-652-3.

- ^ "Cry Freedom: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack". Amazon. 20 March 1987. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Bowman, Durrell (2 September 2016). Experiencing Peter Gabriel: A Listener's Companion. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 93. ISBN 9781442252004. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Cry Freedom (1987). Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". Metacritic.

- ^ "CinemaScore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The New York Times. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ a b Howe, Desson (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom Archived 28 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Variety Staff (1 January 1987). Cry Freedom. Variety. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom[permanent dead link]. At the Movies. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Price, Michael (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Fort Worth Press. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Salisbury, Mark (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Time Out. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Sanford, James (6 November 1987). Cry Freedom. Kalamazoo Gazette. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (5 August 2008). Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide. Signet. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ Simon, John (2005). John Simon on Film: Criticism 1982-2001. Applause Books. p. 178.

- ^ Sirota, David (21 February 2013). "Oscar loves a white savior". Salon. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Cry Freedom: Awards & Nominations". MSN Movies. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom (1987)". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 60th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". Berlin International Film Festival. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". BAFTA.org. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". GoldenGlobes.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "31st Annual Grammy Award Highlights". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Awards for 1987". nbrmp.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Previous Winners". Political Film Society. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". The Numbers. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Universal Postpone Wide Break For 'Freedom'; Eyes Jan.-Feb". Variety. 18 November 1987. p. 11.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for November 19–21, 1988". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Back to the Future: The Fall and Rise of the British Film Industry in the 1980s - An Information Briefing" (PDF). British Film Institute. 2005. p. 21.

- ^ "Cry Freedom VHS Format". Amazon. 5 May 1998. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom: On DVD". MSN Movies. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2010.

- ^ "Cry Freedom: VOD Format". Amazon. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Cry Freedom at IMDb

- Cry Freedom at AllMovie

- Cry Freedom at the Movie Review Query Engine

- Cry Freedom at Rotten Tomatoes

- Cry Freedom at Box Office Mojo

- Cry Freedom film trailer at YouTube

- 1987 films

- 1987 drama films

- Afrikaans-language films

- Apartheid films

- American biographical drama films

- American political drama films

- American epic films

- British biographical drama films

- British political drama films

- British epic films

- Drama films based on actual events

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films about activists

- Films about journalists

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Films based on multiple works

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films directed by Richard Attenborough

- Films produced by Richard Attenborough

- Films scored by George Fenton

- Films scored by Jonas Gwangwa

- Films set in the 1970s

- Films set in 1975

- Films set in 1976

- Films set in 1977

- Films set in 1978

- Films set in 1979

- Films set in Botswana

- Films set in Lesotho

- Films set in South Africa

- Films shot in Kenya

- Films shot in Zimbabwe

- Films with screenplays by John Briley

- South African drama films

- Steve Biko affair

- Universal Pictures films

- Xhosa-language films

- Zulu-language films

- 1980s British films

- Legal drama films

- 1980s American films

- English-language biographical drama films