Tropicana Field

"The Trop" | |

| |

Tropicana Field in 2022 | |

Location in Florida Location in the United States | |

| Former names | Florida Suncoast Dome (1990–1993) ThunderDome (1993–1996) |

|---|---|

| Address | One Tropicana Drive |

| Location | St. Petersburg, Florida, United States |

| Coordinates | 27°46′6″N 82°39′12″W / 27.76833°N 82.65333°W |

| Public transit | 16th Street & 1st Avenue S |

| Owner | City of St. Petersburg |

| Operator | Tampa Bay Rays Ltd. |

| Capacity | 45,369 (1998)[1] 44,027 (1999)[2] 44,445 (2000–2001)[3] 43,772 (2002–2006) 38,437 (2007) 36,048 (2008)[4] 36,973 (2009–2010)[5] 34,078 (2011–2013) 31,042 (2014–2018)[6] 25,025 (2019–present) |

| Record attendance | 48,044, WWE Royal Rumble 2024 |

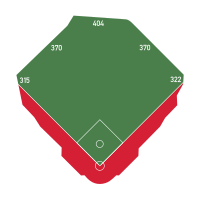

| Field size | Left Field – 315 ft (96 m) Left-Center – 370 ft (110 m) Center Field – 404 ft (123 m) Right-Center – 370 ft (110 m) Right Field – 322 ft (98 m) Backstop – 50 ft (15 m)  |

| Surface | AstroTurf (1998–1999) FieldTurf (2000–2010) AstroTurf GameDay Grass (2011–2017) Shaw Sports Turf (2017–present) |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | November 22, 1986[7] |

| Opened | March 3, 1990 |

| Renovated | 2014[8] |

| Construction cost | US$130 million ($303 million in 2023 dollars[9]) |

| Architect | HOK Sport (Kansas City) Lescher & Mahoney Sports (Tampa) Criswell, Blizzard & Blouin Architects (St. Petersburg) |

| Structural engineer | Martin/Martin Consulting Engineers, Inc. (bowl) Geiger Engineers P.C. (roof) |

| Services engineer | M-E Engineers, Inc.[10] |

| General contractor | Huber, Hunt & Nichols[11] |

| Tenants | |

| Tampa Bay Storm (AFL) (1991–1996) Tampa Bay Lightning (NHL) (1993–1996) Tampa Bay Rays (MLB) (1998–present) St. Petersburg Bowl (NCAA) (2008–2017) WWE ThunderDome (Professional wrestling) (2020–2021) | |

Tropicana Field (commonly known as the Trop) is a multi-purpose domed stadium located in St. Petersburg, Florida, United States. "The Trop" has been the home of the Tampa Bay Rays of Major League Baseball since the team's inaugural season in 1998. The stadium is also used for college football, and from December 2008 to December 2017 was the home of the St. Petersburg Bowl, an annual postseason bowl game. The venue is the only non-retractable domed stadium in Major League Baseball, making it the only year-round indoor venue in MLB. Tropicana Field is the smallest MLB stadium by seating capacity when obstructed-view rows in the uppermost sections are covered with tarps as they are for most Rays games.[citation needed]

Tropicana Field opened in 1990 and was originally known as the Florida Suncoast Dome. In 1993, the Tampa Bay Lightning moved to the facility and its name was changed to the ThunderDome[12] until the team moved to their new home in downtown Tampa in 1996. In October 1996, Tropicana Products, a fruit juice company then based in nearby Bradenton, signed a 30-year naming rights deal.

Tropicana Field's location and design (especially the ceiling catwalks) have been widely criticized, and it is often cited as one of the worst stadiums in Major League Baseball. Major League Baseball itself has cited the need to replace Tropicana Field as one of the primary obstacles to future MLB expansion.[13][14][15]

In 2023, the Tampa Bay Rays announced a deal with local politicians to build Gas Plant Stadium, a new stadium near Tropicana Field at an expected cost of $1.2 billion, half of which would fall on taxpayers.[16] The St. Petersburg City Council blocked a proposal to allow St. Petersburg citizens to express their view on the stadium subsidy in an advisory referendum.[17]

Much of the translucent, fiberglass roof membrane of Tropicana Field was destroyed by Hurricane Milton on October 9, 2024. The stadium had been set up to serve as a base for relief workers.[18] Due to the plans to groundbreak on a new stadium for the Rays, this has left Tropicana Field's future in jeopardy. [19]

History

[edit]After Tampa was awarded the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Tampa Bay Rowdies in the 1970s, St. Petersburg decided it wanted a share of the professional sports scene in Tampa Bay. City officials decided early on that the city would attempt to attract Major League Baseball. Possible designs for a baseball park or multi-purpose stadium were proposed as early as 1983. One such design, in the same location where Tropicana Field would ultimately be built, called for an open-air stadium with a circus tent-like covering. It took several design cues from open-air Kauffman Stadium in Kansas City, Missouri, including fountains beyond the outfield wall.[20]

Ultimately, city officials decided that a stadium with a fixed permanent dome was necessary for a prospective major league team to be viable in the area, due to its hot, humid summers and frequent thunderstorms. Construction began in 1986 in the hope that it would lure a Major League Baseball team to the facility.

1990s

[edit]The stadium was finished in 1990.[21] It hosted the 1990 Davis Cup Finals that autumn, as well as several rock concerts, but still had no tenants. The venue helped make St. Petersburg a finalist in the MLB expansion for 1993, but it lost out to Miami and Denver.[22][23] There were rumors of the Seattle Mariners moving in the early part of the 1990s, and the San Francisco Giants came close to moving to the area, with Tampa Bay investors announcing their purchase of the team and its relocation in a press conference in 1992.[24][25] However, the sale and move were blocked by National League owners, who voted against the deal in November 1992[26] under pressure from San Francisco officials and the then-owner of the Florida Marlins, Blockbuster Video Chairman H. Wayne Huizenga.[27] A local boycott of Blockbuster Video stores occurred for several years thereafter.[28]

The Suncoast Dome finally got a regular tenant in 1991, when the Arena Football League's Tampa Bay Storm made their debut. Two years later, the National Hockey League's Tampa Bay Lightning made the stadium their home for three seasons. In the process, the Suncoast Dome was renamed the ThunderDome.[29] Because of the large capacity of what was basically a park built for baseball, several NHL and AFL attendance records were set during the Lightning and Storm's tenures there.[30][31]

Finally, in 1995, the ThunderDome received a baseball team when MLB expanded to the Tampa Bay area.[32] Changes were made to the stadium and its naming rights were sold to Tropicana Products, which renamed it Tropicana Field in 1996. The relocation of the Lightning and Storm into what is now Amalie Arena in downtown Tampa upon its completion permitted "The Trop" to be vacated for conversion to baseball. A US$70 million renovation then took place—to upgrade a stadium that had cost $130 million to complete only eight years earlier. Ebbets Field was the model for the renovations, which included a replica of the famous rotunda that greeted Dodger fans for many years. The first regular season baseball game took place at the park on March 31, 1998, when the Tampa Bay Devil Rays faced the Detroit Tigers, losing 11–6. Luis Gonzalez of the Tigers hit the first home run at the stadium, followed by Wade Boggs hitting the first Devil Rays homer later that game. Boggs would also hit a home run for his 3,000th hit at Tropicana Field in 1999. Boggs' historic home runs are commemorated with golden seats and plaques where the balls landed in the right field seats.

Although Tropicana was purchased by PepsiCo in 1998, the company refrained from making any changes to the park’s naming rights, as the brand is popular among the local fanbase.[citation needed]

2000s

[edit]The park was initially built with an AstroTurf surface, but it was replaced in 2000 by softer FieldTurf. A new version of FieldTurf, FieldTurf Duo, was installed prior to the 2007 season. It has always featured a traditional "full dirt" infield, instead of the "sliding pits" design that was common during the 1970s and 1980s, making it the first artificial turf field with a full dirt infield since Busch Stadium II in 1976. Since Tropicana Field does not need to convert between baseball and football, sliding pits, designed to save re-configuration time, were unnecessary. Tropicana has hosted football games, but never during baseball season. On August 6, 2007, the AstroTurf warning track was replaced by brown-colored stone filled FieldTurf Duo.

Tropicana Field underwent a further $25 million facelift prior to the 2006 season. Another $10 million in improvements were added during the season. In 2006, the Devil Rays added a live Cownose ray tank to Tropicana Field. The tank is located just behind the center field wall, in clear view of the play on the field. People can go up to the tank to touch the creatures. Further improvements prior to the 2007 offseason, in addition to the new FieldTurf, include additional family features in the right field area, the creation of a new premium club, and several new video boards including a new 35 ft × 64 ft (11 m × 20 m) Daktronics LED main video board that is four times larger than the original video board. The 2007 renovation also added built-in HDTV capabilities to the stadium, with Fox Sports Florida and WXPX airing at least a quarter of the schedule in HD in 2007 and accommodating the new video board's 16x9 aspect ratio.

On September 3, 2008, in a game between the Rays and the New York Yankees, Tropicana Field saw the first official use of instant replay in the history of Major League Baseball. The disputed play involved a home run hit above the left field foul pole by Yankee Alex Rodriguez. The ball was called a home run on the field, but was close enough that the umpires opted to view the replay to verify the call.[33] Later, the Trop saw the first case of a call being overturned by instant replay, when a fly ball by Carlos Peña originally ruled a ground-rule double due to fan interference, was overturned and made a home run on September 19. The umpires determined that the fan in question, originally believed to have reached over the right field wall, did not reach over the wall.[34]

In October 2008, Tropicana Field hosted its first ever baseball postseason games as the Rays met the Chicago White Sox in the American League Division Series, the Boston Red Sox in the American League Championship Series, and the Philadelphia Phillies in the World Series. It hosted the on-field trophy presentations for the Rays when they became the American League Champions on October 19, following Game 7 of the ALCS. Chase Utley hit the first ever World Series home run at Tropicana Field during the first inning of Game 1 of the 2008 World Series. The Rays ended up losing the game 3–2 and eventually the World Series to the Phillies 4 games to 1.

Since 2008, the top ⅓ of the upper deck seating has been tarped over, artificially reducing the stadium's capacity to 36,048 for the 2008 regular season. It was further reduced to 35,041 for the 2008 postseason, since the 300-level Party Deck had been reserved by Major League Baseball as an auxiliary press area. On October 14, 2008, the Rays announced that the upper deck tarps would be removed for the remainder of the postseason, starting with a Game 6 of the 2008 American League Championship Series. This increased the capacity of the stadium to nearly 41,000, depending on standing-room-only tickets sold.[a]

2010s

[edit]

The first no-hitter pitched at Tropicana Field took place on June 25, 2010, thrown by Edwin Jackson of the Arizona Diamondbacks, who had been a member of the Rays from 2006 to 2008.[37]

About one month after Jackson's no-hitter on July 26, 2010, Tropicana Field was the site of the first no-hitter in Rays' history when pitcher Matt Garza achieved the feat. Garza faced the minimum 27 batters, as the only opponent to reach base (on a walk) was erased by a double play hit by the following batter.[38]

On June 24, 2013, in a game against the Toronto Blue Jays, three Rays players – James Loney, Wil Myers, and Sam Fuld – hit consecutive home runs, a first at Tropicana Field.

Because of rioting in Baltimore, a series between the Rays and Baltimore Orioles in May 2015 was moved from Oriole Park at Camden Yards to Tropicana Field. The games were played with the Orioles serving as the home team and the Rays serving as the visiting team.

Due to severe flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey in the Houston area, the Houston Astros played one "home" series at Tropicana Field in August 2017 against the Texas Rangers while the Rays were away on a previously scheduled road trip.[39][40][41] This was only the fourth time games were moved to a neutral location due to weather.[42] Coincidentally, in advance of Hurricane Irma arriving in the Tampa Bay area two weeks later, the Rays' home series against the New York Yankees was moved to Citi Field, the home stadium of the Yankees' crosstown rivals, the New York Mets.

In July 2018, a proposal was unveiled to replace the facility with Ybor Stadium.[43][44] However, later that year at the MLB Winter Owners Meeting, it was announced by Tampa Bay Rays owner Stuart Sternberg that the Ybor stadium plan would not go forward.[45] The current stadium lease between the Rays and the City of St. Petersburg runs through 2027. The city granted the Rays until December 31, 2018, to continue negotiations with Hillsborough County officials. Although MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has stated his support for "the ballpark effort and [his] desire to be [help] in assisting all parties in finding a way to keep the Rays in the Tampa-St. Petersburg area", he also went on to say that the Rays should "explore a path that is in the best interests of his Club and Major League Baseball".[46]

In addition, the relocation announcement sparked a flurry of redevelopment proposals submitted to the City of St. Petersburg.[47] There are proposals to eliminate the structure completely,[48] but efforts have been made to include the public in the debate using several community meetings.[48]

For the 2019 season, Tropicana Field closed its upper decks, as part of efforts and renovations to "create a more intimate, entertaining and appealing experience for our fans". This reduced the stadium's capacity to around 25,000–the lowest in the league. The team's average attendance in the 2018 season was only just over 14,000.[49]

2020s

[edit]From December 2020 to April 2021, the stadium hosted the professional wrestling promotion WWE, broadcasting its shows from a behind closed doors set called the WWE ThunderDome. Due to the start of the 2021 Tampa Bay Rays season, the promotion relocated to Yuengling Center in Tampa.

On January 26, 2021, seven different proposals to redevelop the Tropicana Field site were unveiled, both with and without a new stadium.[50]

The Gas Plant Stadium project is the latest proposal to replace Tropicana Field starting in the 2028 MLB season. This proposal has been approved by both the city of St. Petersburg and Pinellas County commissioners, although construction has not started yet.[51][52] The Rays and Hines plan to begin building the stadium in early 2025, having it ready for Opening Day in 2028.[52][53]

On October 9, 2024, while Hurricane Milton impacted the Tampa Bay region, strong winds tore through Tropicana Field's fiberglass roof. Video showed pieces of the roof flapping in the wind, growing until large sections of the roof were missing.[54] The field level was hosting a base camp for first responders for before and after the storm; at the time the roof ripped, there was nobody on the field, and the Rays clarified that the stadium wasn't being used as a shelter during the hurricane, as a planned precaution of that scenario.[55] According to a principal engineer with the firm that installed the roof in 1990, it had outlasted its original service life by nearly a decade. On October 31, 2024 the St. Petersburg City Council is expected to vote on $6.5 million in remediation, including the removal of the PTFE roof from the field. [56]

Design

[edit]Architectural

[edit]

The most recognizable exterior feature of Tropicana Field is the slanted roof. It was designed at an angle to reduce the interior volume in order to reduce cooling costs, and to better protect the stadium from hurricanes. The dome is supported by a tensegrity structure and is lit up with orange lights after the Rays win a home game. When the Minnesota Twins vacated the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome following the 2009 season and moved into Target Field in 2010, Tropicana Field became the only active Major League Baseball stadium with a fixed (i.e., not retractable) roof. The catwalks attached to the non-retractable roof have been rare but occasional obstructions in the way of batted balls.

The main rotunda, on the east end of the stadium, resembles the Ebbets Field rotunda on the interior. The walkway to the main entrance of the park featured, until the 2020 season, a 900 ft (270 m) long ceramic tile mosaic, made of 1,849,091 one-inch-square tiles. It was the largest outdoor tile mosaic in Florida, and the fifth-largest in the United States. It was sponsored by Florida Power Corporation, which is now a part of Duke Energy.[57]

The primary 100-level concourse is at street level, with elevators, escalators and stairs separating the outfield and infield sections, since the ground is at different grades on either side. The 200-level loge box concourse is further separated, and is carpeted, as it includes the entrances to most of the luxury suites. The 300-level concourse is the highest of the concourses.

Gates

[edit]There are seven gate entrances/exits to Tropicana Field, numbered in a clockwise fashion. Gate 1 is the main entrance, known as the Rotunda, on the right-field side of the stadium. Gate 4 is a VIP-only entrance, while Gate 7 is for stadium and team personnel only.

Dining and amenities

[edit]| Rays Home Attendance at Tropicana Field | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Attendance | Avg./Game | Rank |

| 1998 | 2,506,293 | 30,942 | 7th |

| 1999 | 1,562,827 | 19,294 | 10th |

| 2000 | 1,449,673 | 18,121 | 13th |

| 2001 | 1,298,365 | 16,029 | 14th |

| 2002 | 1,065,742 | 13,157 | 14th |

| 2003 | 1,058,695 | 13,070 | 14th |

| 2004 | 1,274,911 | 15,936 | 14th |

| 2005 | 1,141,669 | 14,095 | 14th |

| 2006 | 1,368,950 | 16,901 | 14th |

| 2007 | 1,387,603 | 17,131 | 14th |

| 2008 | 1,811,986 | 22,370 | 12th |

| 2009 | 1,874,962 | 23,148 | 11th |

| 2010 | 1,864,999 | 23,025 | 9th |

| 2011 | 1,529,188 | 18,879 | 13th |

| 2012 | 1,559,681 | 19,255 | 14th |

| 2013 | 1,510,300 | 18,646 | 15th |

| 2014 | 1,446,464 | 17,858 | 14th |

| 2015 | 1,287,054 | 15,322 | 15th |

| 2016 | 1,286,163 | 15,879 | 15th |

| 2017 | 1,253,619 | 15,477 | 15th |

| 2018 | 1,154,973 | 14,259 | 15th |

| 2019 | 1,178,735 | 14,552 | 15th |

| 2020 | 0 | 0 | - |

| 2021 | 761,072 | 9,396 | 14th |

| 2022 | 1,128,127 | 13,927 | 14th |

| 2023 | 1,440,301 | 17,781 | 13th |

| 2024 | 1,337,739 | 16,515 | 14th |

| Source:[58] | |||

Seating at Tropicana Field is arranged with odd sections on the third base side and even sections on the first base side. The hallway behind sections 133–149 is nicknamed "Left Field Street." The hallway behind sections 136–150 is nicknamed "Right Field Street." The 100-level seating wraps around the entire field with a 360° walkway. Behind the stadium's batter's eye is a center field common area, known as The Porch, which provides fans with open seating and standing room to watch games. The Porch, along with other facility improvements, was part of a multimillion-dollar renovation project that was completed before the start of the 2014 season.[59] Loge boxes are featured along the infield of the 100-level from foul pole to foul pole. 200-level seating features 20 sections along the foul lines, broken by the press box behind home plate, with the luxury boxes directly behind and above them. 300-level seating wraps around the infield along the lines, and also features the "Party Deck", a small-capacity seating area above the left field outfield seats with separate concessions inside; initially sponsored by tbt*, the Party Deck has been sponsored by GTE Financial since the 2019 season. Rows are lettered starting closest to home plate and rise further away. Seats are numbered starting at the left side of the section.

There are a total of 70 luxury suites with 48 accessible from the 200-level, while the other 15 are located on the 100-level.[citation needed]

There are a total of 2,776 club seats at Tropicana Field. The Dex Imaging Home Plate Club features its own entrance, recliner seats, and a premium buffet with in-seat service. The second club section, the Rays Club, is along the first-base side on the 100-level at the Loge Box level. It features its own premium buffet and premium seating.

MacDillville is a section located on the right field line, behind the Rays' bullpen. The section is reserved for the 24 tickets that the Rays provide to personnel returning from deployment, families of deployed personnel and staff assigned to MacDill Air Force Base.[60]

Field-level party sections were installed in the corners in 2006. The left field party section is available for groups of 75-136 people and named "162 Landing", in reference to Evan Longoria's walk-off home run in the 162nd and final regular season game of the 2011 season that landed in that section, which clinched the American League wild card for the Rays. In 2017 the section was renamed after the Tampa sports bar, "Ducky's" that is featured in The Porch, and co-owned by Evan Longoria; the Ducky's branding was removed following the trade of Longoria to the San Francisco Giants before the 2018 season, and 162 Landing has been sponsored by Hard Rock Café since the 2018 season. The right field party section is the "Papa John's Bullpen Box" and is available for groups of 50–85. When the right field corner was sponsored by the fast food chain Checkers, tickets to the "Checkers Bullpen Cafe" included a free meal at the Checkers kiosk immediately adjacent to the section. As of 2008, both party sections featured all-you-can-eat buffets.

In 2019, the Rays introduced the Left Field Ledge, a party section above the section of the 360 walkway behind left field, offering tables for groups of eight and patio boxes for groups of 12 to 24.[61]

The St. Anthony's Fan Care Clinic is located between Gates 3 and 4 on the 100 level, section 102 (behind home plate). St. Anthony's Health Medical Team staffs the clinic and offers first aid services to fans.[62] A Baby Care Suite is located on the 300 level near section 300. It features baby changing stations and private nursing suites.

One of the team's two main apparel stores is located in the stadium, near gate 1. The other main store, The Tampa Pro Shop & Ticket Outlet, is located in Tampa. Many specialty, smaller, stores are located throughout the stadium, including a "Game-Used Merchandise" store located in Center Field Street.[62]

The Rays Touch Tank

[edit]

Just over the right-center field fence is the Rays Touch Tank. This 35-foot (11 m), 10,000 US gallons (38,000 L; 8,300 imp gal) tank is filled with three different species of rays, including cownose rays that were taken from Tampa Bay waters. The tank is one of the 10 biggest in the nation[clarification needed][citation needed]. Admission to the tank area is free for all fans attending home games, but there is a limit of 40 people in the area at any given time. The tank is open to fans about twenty minutes after the gates open and closes to the public two hours after the first pitch. Fans get to see the rays up close and get to learn educational info about them.

The tank and rays are sponsored and maintained by the Florida Aquarium, and educates people about rays and other aquatic life.

For every ball hit into the tank during a game by a Rays player, the Rays would donate $5,000 to charity with $2,500 going to the Florida Aquarium and $2,500 going to that player's charity of choice.[63] As of the 2021 season, the netting over the tank was extended to fully enclose the area, removing the possibility of a home run ball entering the tank.

Before that, only two Rays players hit a home run that landed in the tank:

| Touch Tank Home Runs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hitter | Date | Charity |

| José Lobatón* | October 7, 2013[64] | Tampa Children’s Home[65] |

| Brad Miller | July 31, 2016[66] | Mikie Mahtook Foundation[67] |

* Denotes walk-off home run.

In addition, only five players hit home runs into the tank playing for opposing teams:

| Hitter | Team | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Luis Gonzalez | Los Angeles Dodgers | June 24, 2007[68] |

| Miguel Cabrera | Detroit Tigers | June 30, 2013[69] |

| Nelson Cruz | Seattle Mariners | May 27, 2015[70] |

| Robbie Grossman | Minnesota Twins | September 5, 2017[71] |

| Kole Calhoun | Los Angeles Angels | August 1, 2018[72] |

Concessions

[edit]Behind center field on the stadium's ground level near the main rotunda entrance is a two-story full-service restaurant and recreational area called BallPark & Rec, opened in 2018. The restaurant's second floor features an outdoor area with lawn games, as well as an indoor arcade area.[73] This restaurant took over the location previously occupied by Everglades Brewhouse, which served several craft beers in addition to having a full liquor bar and opened two hours before first pitch. A "Fan vs. Food" challenge at Everglades was introduced in 2014, which consists of eating a 4-pound (1.8 kg) burger and a pound of french fries in under 30 minutes to win two future Rays game tickets and a T-shirt.[74]

Various other concession stands are located behind center field and along the outer rim of the stadium along the base lines, collected in three concourses named Center Field Street, First Base Food Hall, and Third Base Food Hall. These stands frequently change from season to season, are often named after or maintained by stadium sponsors, or are themed after notable Rays figures, such as the Rocco Ball Deli, themed after former Rays player and coach Rocco Baldelli, which was open for the 2018 season until Baldelli was hired by the Minnesota Twins in 2019.[75] Current and former concessions include the Taco Bus, the Wine Cellar, The Carvery, Pipo's, Papa John's Pizza, Fish Shack, Everglades BBQ, a full service liquor bar, Bay Grill and the Craft Beer Corner featuring many local craft brewery's including Big Storm Brewing, Cigar City, Green Bench, Sea Dog and 3 Daughters. Green Bench Brewing offers a special edition brew just for the Rays called 2-Seam Blonde Ale.[76]

In addition to these concessions, Tropicana Field previously hosted a concession stand for Outback Steakhouse. Outback is a Tampa Bay-based establishment. To compete with established stadiums' hot dog traditions, the Trop introduced the "Sting 'Em" Dog in 2007. This consists of a regular hot dog topped with chili and cheese.[77] It was renamed "The Heater" in 2008.

Ted Williams Museum/Hitters Hall of Fame

[edit]For a list of inductees and recipients of various awards, see footnote[78]

The Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame[79][80] opened in February 1994,[81] in Hernando, Florida,[82] in Citrus County—just a few blocks from the place where Williams lived in his later years.[81]

In 2006, the museum and hall of fame were moved to Tropicana Field after its original facility in Hernando went bankrupt. A new 7,000-square-foot (650 m2) upstairs wing was opened in 2007, which now houses the exhibits on Ted Williams's careers with the Boston Red Sox and with the United States Marine Corps[82][83] during World War II and the Korean War, as well as the monuments to the members of the Hitters Hall of Fame complete with memorabilia, with donated authentic memorabilia wherever possible and many of Williams's own personal mementos from his career and post-playing life. Williams did not induct himself into his own Hitters Hall of Fame, and was inducted in 2003 only after he died.

The museum also includes a "Pitching Wall of Great Achievement",[82] the Negro leagues wing[82]—including an exhibit about John Jordan "Buck" O'Neil (a "son" of Sarasota)[82]—the "500 Homerun Club" exhibit,[82] and exhibits about other topics, including the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League[82] and the Tampa Bay Rays.[82] The museum often hosts autograph signings and charity auctions during or before games.

The museum is open during game days, opening at the same time as the park and closing after the 7th inning with the concession stands. Admission is free, and the museum is open to all ticketholders.[81][82] In 2012, the museum is open until the 9th inning, but still open only on game days. As of the last week of the 2012 season the museum was back to closing by the 7th inning (beginning of, not after the 7th inning) and the open only on game days policy is still in effect.

Notable events

[edit]Basketball

[edit]In 1998, Tropicana Field was a regional final site for the NCAA men's basketball tournament. A year later the stadium played host to the 1999 Final Four which saw the Connecticut Huskies beat the Duke Blue Devils 77–74 for the championship. Subsequently, no other NCAA men's basketball game has been played at Tropicana Field.

Football

[edit]ArenaBowl IX was held at the venue in 1995.

In 2008, the NCAA announced that Tropicana Field would be host to a postseason college bowl game, bringing football to the dome.[84] The game, which eventually took on the name Gasparilla Bowl, was played inside Tropicana Field until 2017, after which the bowl organizers moved the annual contest to Raymond James Stadium in Tampa.[85]

The Trop returned to a football configuration on October 30, 2009, to host one of the three home games of the Florida Tuskers of the United Football League, which the Rays had invested in.[86]

The East–West Shrine Game, a postseason college football all-star game played annually since 1925, was played at Tropicana Field from 2012 until 2019.[87]

Hockey

[edit]Tropicana Field, then known as the ThunderDome, holds the record for the highest attendance for a Stanley Cup playoffs game, set on April 23, 1996, with 28,183 fans.[88] At the time this was the largest-ever crowd at an NHL game, which stood until the 2003 Heritage Classic. This still stands the attendance record for a game played at a team's regular home stadium, as all NHL games with a higher attendance were part of the NHL's Winter Classic, Heritage Classic, or Stadium Series.

Motorsports

[edit]The World of Outlaws Sprint Cars raced at the Suncoast Dome on February 7–9, 1992 as a part of Florida Speedweeks with several tracks hosting events during the month.[89]

An SCCA Trans-Am Series race was held from 1996 to 1997 on a temporary course encompassing the parking lot and surrounding streets.

Concerts

[edit]Tropicana Field has hosted many concerts over the years; one of the first large events upon its completion was a concert by Don Henley on June 29, 1990.[citation needed] Many well-known artists have held concerts at the venue, including Eric Clapton (twice), David Bowie, Janet Jackson (twice), Steely Dan, AC/DC (twice), Guns N' Roses, Billy Joel (twice), Robert Plant, Rush (twice), R.E.M., the Eagles, Depeche Mode, Rod Stewart, Kiss, and Van Halen (twice), among others.[90][91] The venue's largest concert attendance was for the boy band New Kids on the Block in August 1990.

The number of large concerts at Tropicana Field has decreased considerably since the (Devil) Rays were established in 1998, as the club's 81-game home schedule makes scheduling difficult, especially during the summer concert season. Also, the development in nearby Tampa of Amalie Arena (opened in 1996) and the MidFlorida Credit Union Amphitheatre (opened in 2004) into busy concert venues has further curtailed the concert slate at Tropicana Field.[92][93]

Rays Summer Concert Series

[edit]Beginning in 2007, the Rays organized a "Summer Concert Series" in which a mix of major and lesser-known performers of many different musical genres performed after select home games for no extra charge beyond the price of the game ticket. The concerts were usually scheduled after Friday or Saturday night games, with more kid-oriented acts performing after Sunday afternoon games. The usual procedure was for a portable stage to be rolled out onto centerfield immediately after the final out of the ballgame, with the music starting soon thereafter. For most shows, fans were allowed to come down onto the playing field to watch the performance up close.

The first after-baseball concert featured nostalgia act Sha Na Na in June 2007. The event was so successful that the Rays booked a series of shows for the following season, usually increasing attendance for those games. Participating artists have included The Beach Boys, Los Lobos, LL Cool J, Sister Hazel, Kacey Musgraves, The Jacksons, REO Speedwagon, ZZ Top, Weezer, Kenny Loggins, Avril Lavigne, Joan Jett, and The Wiggles among many others, totaling over 80 shows in all.[94][95][96]

In some seasons, the number of post-game concerts was as high as a dozen. The number dwindled to two in 2017, and before the 2018 season, the Rays announced that they would discontinue the concert series due to "stress on the artificial turf".[92]

On April 27, 2023, the Rays announced that the Summer Concert Series would return to celebrate their 25th anniversary season. The first artist announced was AJR, who would perform after the Friday, May 19 game against the Milwaukee Brewers.[97] The concert proved to be a success, and the team soon announced two more acts, Lee Brice on Friday, August 11, and the "I Love The 90's" Tour, featuring Vanilla Ice, Rob Base, Montell Jordan, and Tone Loc, on Friday, September 8.[98]

Professional wrestling

[edit]On December 11, 2020, professional wrestling promotion WWE began broadcasting its weekly shows, Raw, SmackDown, and Main Event, and their associated pay-per-view (PPV) and livestreaming events from Tropicana Field in a residency. The programs were filmed behind closed doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic in a bio-secure bubble called the WWE ThunderDome, which had been relocated from Orlando's Amway Center due to the start of the 2020–21 ECHL and NBA seasons as the Amway Center is the shared home of the Orlando Solar Bears and the Orlando Magic.[99]

Through the arrangement, Tropicana Field hosted the pay-per-views TLC: Tables, Ladders & Chairs, Royal Rumble, Elimination Chamber, and Fastlane—the final PPV before WrestleMania 37 (hosted by Raymond James Stadium in nearby Tampa)—as well as the 2021 WWE Hall of Fame induction ceremony, and WWE Superstar Spectacle (a WWE Network event produced primarily for the Indian market). As the 2021 MLB season approached, on March 24, 2021, WWE announced that the ThunderDome would be relocated to the Yuengling Center in Tampa, beginning with the April 12 episode of Raw, the night after WrestleMania 37. WWE's final show filmed at Tropicana Field was the April 9 episode of SmackDown, which was taped the week prior on April 2.[100]

WWE would return to Tropicana Field for the 2024 Royal Rumble event,[101] which set an attendance record of a reported 48,044 fans.[102]

Criticism

[edit]Location

[edit]Tropicana Field sits on 66 acres (27 ha) in the Midtown community of St. Petersburg, Florida. The land the stadium and its parking lots now occupy was occupied by the Gas Plant neighborhood from the late 1800s until 1986.

In the late 1800s St. Petersburg began a large recruitment initiative to attract people to help build the city's infrastructures and fill lower-income service jobs. African Americans began to move to St. Petersburg from across the south looking to fill these jobs. The influx of African Americans in the area brought the formation of many black communities including the Gas Plant district. The area housed nearly 800 people,[103] many African American-owned small businesses and three African American churches. The district's name came from the two fuel tanks that originally stood where Tropicana Field now stands.

In 1979, the St. Petersburg City Council voted to refurbish the neighborhood, as it had "seen better days."[104] This plan promised to create new, modern, affordable housing and an industrial park that would bring many new jobs to the area. By 1982 developers offered no proposals for the refurbishment of the district to the city council, even after the council specifically requested the proposals. A group of Pinellas County business people offered a plan to the council that entailed building a baseball stadium, in hopes of attracting a major league baseball team to the area. That year, the council voted unanimously to follow through with the baseball hopes and lease the land to the sports authority for $1 a year.

Most African Americans who used to live or work in the neighborhood felt betrayed by the city and bitter over the baseball development. The city had offered, and followed through with, many reparation programs for the residents and businesses of the Gas Plant district when the district was originally to be refurbished, including financial relocation help. But these programs were welcomed only on the basis that the area would be once again a functional community. When that stipulation changed residents were angered and new reparation plans were rumored but never came to fruition. As for the churches of the area, relocation offers extended to them from the City Council were "generous" according to one of the churches pastors. This is believed to be because of the political power that the churches held.[104]

The destruction of the Gas Plant district and the city's shortcomings in securing economic and employment opportunities for the displaced African American community have left a jagged relationship between city officials and the aforementioned African American community. The destruction of the Gas Plant district financially crippled and killed many African American-owned small businesses and is often referred to as the main reason that only 10% of St. Petersburg's small businesses are African American-owned today.

The dome was built on the former site of a coal gasification plant and, in 1987, hazardous chemicals were found in the soil around the construction site. The city spent millions of dollars to remove the chemicals from the area.[105]

It is often criticized as being located away from the Tampa Bay area's largest population base in Tampa.[106][107]

Catwalks

[edit]Among the most cited criticisms about the stadium are the four catwalks that hang from the ceiling. The catwalks are part of the dome's support structure. The stadium was built with cable-stayed technology similar to that of the defunct Georgia Dome. It also supports the lighting and speaker systems. Because the dome is tilted toward the outfield, the catwalks are lower in the outfield.

The catwalks are lettered, with the highest inner ring being the A Ring, out to the farthest and lowest, the D Ring. The A Ring is entirely in play, while the B, C, and D Rings have yellow posts bolted to them to delineate the relative position of the foul lines. Any ball touching the A Ring, or the in-play portion of the B Ring, can drop for a hit or be caught for an out. The C and D Rings are out of play; if they are struck between the foul poles, then the ball is ruled a home run.

On August 5, 2010, Jason Kubel of the Minnesota Twins hit a sky-high infield pop-up that would have ended the inning in a 6–6 game if caught, but the ball struck the A ring and fell safely onto the infield allowing the Twins to score the go-ahead run and extend the inning in a controversial 8–6 win.[108] As a result, on October 4, 2010, Major League Baseball approved a change in the ground rules for the A and B rings, making it so that a batted ball striking either of the two rings was automatically ruled a dead ball, regardless of whether the ball strikes in fair or foul territory. The rules pertaining to the C and D rings remained the same.[109] This change lasted for just the 2010 postseason.[110]

On the other hand, several potential hits have been lost as a result of the catwalks. For example, on May 12, 2006, Devil Rays outfielder Jonny Gomes hit a long fly ball against the Toronto Blue Jays that seemed destined to be a home run before it hit the B ring, got stuck momentarily, and then rolled off and was caught by Toronto shortstop John McDonald as Gomes was headed for home plate. Although Rays manager Joe Maddon tried to argue that it should have been at least a ground rule double since it stayed in the B Ring for a while before coming loose, umpires eventually ruled against the Rays and called Gomes out.

On May 26, 2008, Carlos Peña hit a pop-fly to center field that likely would have been caught by Texas Rangers center fielder Josh Hamilton. The ball instead hit the B ring catwalk and did not come down. Peña was mistakenly given a home run, but after deliberation, the umpires awarded him a ground rule double. This was the second time this had happened, as José Canseco hit a ball that stuck in the same catwalk on May 2, 1999.[111]

Many players have hit the C and D rings for home runs. The first player ever to hit the rings for a home run was Edgar Martínez of the Seattle Mariners on May 29, 1998. Martinez's home run went off the D ring. Three players before him hit balls that went into the C ring. However, at the time, balls hitting the C ring were not ruled home runs. Two days prior to Martinez's home run, the ground rules were changed so that if a ball hit the C ring, it would be called a home run.[112] The first player to hit the rings for a home run in postseason play was Rays third baseman Evan Longoria, who hit the C ring off Javier Vázquez of the Chicago White Sox on October 2, 2008, in the 2nd inning of Game 1 of the 2008 American League Division Series.

On July 17, 2011, against the Red Sox, Rays batter Sean Rodriguez hit a high foul popup that shattered a lightbulb on a catwalk. Pieces of the broken bulb fell to the turf near the third base coach's box. After a quick cleaning delay in which the Tropicana Field PA system played the theme to The Natural (a 1984 film that prominently features a hit baseball striking and shattering a stadium light fixture), the game resumed.

Another ceiling-related incident came in June 2018, when New York Yankees outfielder Clint Frazier's 9th-inning fly ball bounced off a speaker hanging from the B ring and was caught by Rays shortstop Adeiny Hechavarria for an out. Some suggest that the ball would have traveled far enough for a home run, which would have broken a 6–6 tie. The Rays won the game in extra innings with a walk-off home run.[113]

Bullpens

[edit]The bullpens are located along (and close to) the left and right field foul lines and there are no barriers that separate them from the field of play. In fact, fly balls hit into the bullpens are in play. The bullpen players and the pitching mounds are obstacles for fielders chasing fly balls into the pen. Teams have to station a batboy behind the catchers in the bullpens to prevent them from being hit by foul balls from behind. This style of bullpen used to be common in the Major Leagues, but is currently in use only at Tropicana Field (the Oakland Coliseum has this feature but the stadium does not have an MLB tenant following the departure of the Oakland Athletics following the 2024 season).

Interior

[edit]

Another criticism of the stadium is the drab interior environment, especially early in the (Devil) Rays' existence, when the stark concrete interior was compared to a large warehouse. However, since it was designed specifically for baseball, it is somewhat smaller and the sightlines are better than in most domed stadiums, which are often built to accommodate other sports as well.

The current Rays' Stuart Sternberg-led ownership group has invested several million dollars over the past decade to make the venue more fan friendly. New or improved features include a larger scoreboard, video wall, catwalk sleeves, an outfield touch-tank featuring cownose rays, a walk-around that circles the entire field, two concession and gathering areas in the outfield, and many other additions and upgrades designed to improve the fan experience.[114][115]

See also

[edit]- Amalie Arena, home of the Tampa Bay Lightning and former home of the defunct Tampa Bay Storm

- Raymond James Stadium, home of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the South Florida Bulls football team

- Rays Ballpark, a former proposed new stadium for the Tampa Bay Rays that has since been abandoned

- Rays Park at Carillon, a second former proposed stadium for the Tampa Bay Rays that was abandoned in mid-2015

- Charlotte Sports Park, the spring training home of the Tampa Bay Rays, located in Port Charlotte, Florida

- Caesars Superdome, another stadium that had been damaged by a landfalling major hurricane while in use for operations surrounding the storm

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "1998 Tampa Bay Devil Rays Schedule, Box Scores and Splits". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Parks, Kyle (March 7, 1999). "More Than Just Show". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved April 4, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ LaPeter, Leonora (July 31, 2001). "Trop Given 90 Days to Fix Disabled Access". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Rays' home opener officially sold out". raysbaseball.com. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Major league baseball preview: What's new at the Trop". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Chastain, Bill (December 3, 2013). "Rays Provide Glimpse of Significant Trop Renovations". Major League Baseball Advanced Media. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Stadium Ground Broken". Boca Raton News. November 24, 1986. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Ortiz, Jorge (March 31, 2014). "New renovations aimed to draw fans to Tropicana Field". USA Today. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Detroit Tigers to roar in Comerica Park". www.achrnews.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Ballparks.com – Tropicana Field". www.Ballparks.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Davey, Monica (July 31, 1993). "That rumbling's not so distant". Tampa Bay Times. p. 1B. Retrieved October 14, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gartland, Dan (March 28, 2023). "Ranking All 30 MLB Stadiums from Worst to Best". SI.com. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ Joseph, Andrew (March 25, 2023). "All 30 MLB stadiums, ranked: 2023 edition". ForTheWin. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ Rosenthal, Ken (January 11, 2021). "MLB expansion is on hold, despite some financial incentives". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 19, 2024. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ Rosenthal, Ken (September 18, 2023). "Rays announce deal for new stadium in St. Petersburg to open in 2028: Baseball is 'here to stay'". The Athletic. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ^ Parker, Mark (November 2, 2023). "St. Pete residents will not vote on Rays stadium deal". St Pete Catalyst. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ "Tropicana Field roof ripped off by Hurricane Milton's winds". ABC Action News Tampa Bay (WFTS). October 10, 2024. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Axelbank, Evan (October 16, 2024). "Multi-million dollar project: The Rays unsure of the Trop's future". FOX 13 News. Retrieved October 17, 2024.

- ^ "Rays stadium debate topic page". blogs.tampabay.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ White, Russ (February 25, 1990). "Florida Suncoast Dome: A Gem Without A Diamond St. Petersburg's $309 Million Arena To Open Saturday". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Cooper, Barry (June 11, 1991). "Plan Goes Awry In St. Pete". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Clary, Mike (March 8, 1993). "They built a field of dreams, but no one came : A city's $138-million baseball showcase fails to lure a big-league team". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Chass, Murray (August 8, 1992). "BASEBALL; Baseball's Giants Reach Agreement To Move To Florida". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Newhan, Ross (August 8, 1992). "S.F. Giants Owner Agrees to Sell to Tampa Bay Group". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Chass, Murray (November 11, 1992). "BASEBALL; Look What Wind Blew Back: Baseball's Giants". The New York Times. p. B11.

- ^ Chass, Murray (August 13, 1992). "ON BASEBALL; A Not-So Moving Story". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ Hersch, Hank (August 1992). "Tale of Four Cities". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013.

- ^ Buckley, Tim (October 10, 1993). "Lightning's spark? It was on the bench". Tampa Bay Times. p. 6C. Retrieved October 14, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "25,945! An NHL-Record Crowd Cheers The Lightning On To Victory". St. Petersburg Times. April 22, 1996. p. 12c. Retrieved October 14, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Storm". www.tampabaystorm.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2006. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL IN TAMPA BAY". www.congress.gov. March 13, 1995. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Chastain, Bill (May 24, 2013). "Instant replay used for first time". MLB.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013.

- ^ Chastain, Bill (September 19, 2008). "Rays happy with instant replay results". MLB.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2008.

- ^ "2008 American League Championship Series (ALCS) Game 6, Boston Red Sox vs Tampa Bay Rays: October 18, 2008". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ "2008 American League Championship Series (ALCS) Game 7, Boston Red Sox vs Tampa Bay Rays: October 19, 2008". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Joe (June 25, 2010). "Ex-Ray Edwin Jackson Throws No-Hitter Against Tampa Bay". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Topkin, Marc (July 26, 2010). "Garza Has Rays First No-Hitter". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on July 30, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Witz, Billy (August 29, 2017). "A Houston Astros Home Series Is Moved to Florida". The New York Times.

- ^ Shaikin, Bill (August 29, 2017). "Rangers happy to help flood-displaced Houston Astros ... but only to a point". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Rangers criticized for declining series swap". ESPN. August 28, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ "Choo paces Rangers' 12-2 rout of Astros in Florida". ESPN. Associated Press. August 29, 2017.

- ^ Gardner, Steve (July 10, 2018). "Rays unveil plans to build smallest stadium in baseball to replace Tropicana Field". USA Today. Retrieved October 14, 2024.

- ^ "Rays unveil plans for new ballpark with a roof that'll reportedly cost $240 million". CBS Sports. July 10, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ Roa, Ray (December 11, 2018). "Tampa Bay Rays owner Stu Sternberg says there'll be no new stadium in Ybor City". Creative Loafing.

owner Stuart Sternberg said that his team's $892 million stadium plan for historic Ybor City has fallen apart

- ^ Tompkin, Marc (December 11, 2018). "MLB commissioner Rob Manfred blasts plans for Rays stadium". Tampa Bay Times.

- ^ "So, what's next for the Tropicana Field site?". www.baynews9.com. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ a b "Architects planning for Trop site without stadium". www.baynews9.com. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ "How low can you go: Rays close off upper deck". ESPN.com. January 4, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2021.

- ^ "Here are the 7 proposals to redevelop Tropicana Field site in St. Petersburg". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ Wright, Colleen (July 18, 2024). "'We are St. Pete!': Rays stadium, redevelopment approved by city council". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Evans, Jack. "Pinellas Commission approves Rays stadium deal: The 5-2 vote was the last major hurdle for the stadium project". tampabay.com/. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Rays, Hines celebrate approval of new ballpark, Historic Gas Plant District Development". mlb.com/. Major League Baseball. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Sanders, Hank (October 10, 2024). "Hurricane Milton Destroys Roof of Tropicana Field Stadium". The New York Times. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Lagatta, Eric (October 8, 2024). "Tropicana Field transformed into base camp ahead of Hurricane Milton: See inside". USA Today. Retrieved October 10, 2024.

- ^ Blum, Sam (October 10, 2024). "Age of Tropicana Field roof played role in Hurricane Milton damage, stadium engineer says". The Athletic. The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Tropicana Field". Tampa Bay Rays. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Rays Attendance". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ "Tampa Bay Rays unveil new 360-degree walkway around Tropicana Field". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Community Player Programs". Tampa Bay Rays. Archived from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "2019 Preview: Tampa Bay Rays, Tropicana Field". Ballpark Digest. March 27, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Tropicana Field A-to-Z Guide". Tampa Bay Rays. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "Rays Tank". Tampa Bay Rays. Archived from the original on March 22, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Rays stay alive, beat Red Sox on Jose Lobaton walk-off home ru". Sporting News. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- ^ "Rays notebook: That rumor that a Red Sox fan grabbed a ray from the tank and threw it? Not true". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- ^ Cosman, Ben (July 31, 2016). "Brad Miller homers into the Tropicana Field Touch Tank and sets a record in the process". MLB.com. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ 5.1K views · 94 reactions | Brad Miller's splash landing | Brad Miller directed #Rays Baseball Foundation's $2,500 donation to Mikie Mahtook Foundation, in addition to The Florida Aquarium, after Sunday's splash... | By Tampa Bay Rays | Facebook. Retrieved October 24, 2024 – via www.facebook.com.

- ^ "Gonzalez homers, but Dodgers sink". Los Angeles Dodgers. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Video: DET@TB: Miggy's solo homer ties the game in fourth". Wapc.mlb.com. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "Felix Hernandez bests Chris Archer with four-hit shutout". Seattle Mariners. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Grossman's solo splashdown". MLB.com. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- ^ "Adames, Bauers power Rays to 7-2 home victory". Youtube.com. August 2018. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "BallPark & Rec is expanding into a two-story full-service restaurant at Tropicana Field". Creative Loafing. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ Astleford, Andrew (March 28, 2014). "Rays unveil 4-pound 'Fan vs. Food' burger at Tropicana Field". FOX Sports. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Rays and Levy introduce renovated facilities and new menu items for 2018". MLB.com. 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ "Rays add Pipo's, Green Bench craft beer and Longoria's Ducky's to Tropicana Field menu". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "Taste: Hot diggity dogs". www.sptimes.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Ted Williams Museum Inductees to Date". Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame official website. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Home page". Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame official website. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame official website. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c "About the Museum". Ted Williams Museum and Hitters Hall of Fame official website. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Video tour of the museum and hall of fame. "Inside the Rays: Odd Jobs". Fox Sports Florida. FOX Sports Interactive Media, LLC. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ See also: United States Navy Baseball#History.

- ^ "NCAA approves St. Petersburg Bowl" from St. Petersburg Times, May 1, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ "Gasparilla Bowl moving from Tropicana Field to Raymond James Stadium". May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Gary Shelton. "The Tampa Bay Rays' investment in the Florida Tuskers of the United Football League prompts unfounded paranoia". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ "East–West Shrine Game Moving to St. Petersburg's Tropicana Field". East–West Shrine Game. April 27, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ Kreiser, John (April 23, 2017). "Lightning made NHL history at Thunderdome". NHL.com. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ "Build It". Beaver County Times. May 23, 2000. Retrieved June 8, 2016 – via Google News Archive Search.

- ^ "Thunderdome, St. Petersburg". Setlist.f. 1995.

- ^ "Suncoast Dome, St. Petersburg". Setlist.fm. 1990.

- ^ a b Cridlin, Jay (March 28, 2018). "Rays: No postgame concerts at Tropicana Field in 2018". tampabay.com. Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Gurbal Kritzer, Ashley (August 3, 2017). "Amalie Arena ranks among top venues across the globe for concert and event ticket sales". www.bizjournals.com. Tampa Bay Business Journal. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ "Rays announce summer concert series". Tampa Bay Newspapers. March 20, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- ^ Cridlin, Jay (July 21, 2015). "Rays concert series brings life, and a few extra fans, to the Trop". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- ^ "Rays Add Sister Hazel to 2015 Summer Concert Series". MLB News. June 26, 2015.

- ^ "Rays announce postgame concert on May 19 to kick off Summer Concert Series". MLB.com. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ "Rays add two postgame concerts to Summer Concert Series". MLB.com. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (November 19, 2020). "WWE to Move ThunderDome to Tropicana Field in Tampa Bay". Variety. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Randall (March 24, 2021). "WWE Moves ThunderDome to USF's Yuengling Center". Sportico.com. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "WWE Royal Rumble 2024 date, location: Tampa Bay to host annual event in January to kick off new year". CBSSports.com. September 13, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ Hetfield, James (January 28, 2024). "WWE Royal Rumble 2024 Sets New Attendance Record At Tropicana Field". PWMania. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ "Build a Stadium, Raze a Neighborhood". Creative Loafing: Tampa Bay. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Lavin, Rochelle Lewis. "Around the dome, echoes of the past". faculty.usfsp.edu. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "St. Pete Ballpark Opponents Hope Dirt Contaminates Plan". The Suncoast News. March 26, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

The site received a $7 million cleanup before the domed stadium was built in the late 1980s. More contaminated dirt was removed when the stadium underwent renovation for the arrival of Major League Baseball in 1998.

- ^ "Rays Style A Fan Base". The Tampa Tribune. October 1, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "No Ideal Site in Mid Pinellas Stadium for Tampa Bay Rays". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "Dome-Clanking Popup Leaves Rays in Dumps". St. Petersburg Times. August 5, 2010. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Topkin, Marc (October 4, 2010). "Catwalk Rules Changed for Postseason". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on October 7, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2010.

- ^ Chastain, Bill (March 15, 2011). "Ground rules changed at the Trop for 2011". MLB.com. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Maffezzoli, Dennis (May 27, 2008). "Ace Leads Tampa Bay to the Best Record in the Majors". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "AMERICAN LEAGUE: ROUNDUP; Wind Blows The Indians' Direction". The New York Times. May 29, 1998. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ Page, Rodney (June 24, 2018). "Rodney Page's takeaways from Sunday's Rays-Yankees game". tampabay.com. Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ "Tampabay: No stadium in on-deck circle". www.sptimes.com. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Krueger, Curtis (March 28, 2014). "Tampa Bay Rays unveil new 360-degree walkway around Tropicana Field". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Martínez, Michael (March 5, 1990). "A Dome Fit for Expansion?". The New York Times.

- Choi, Andrew; Park, Roger (2011). "Visual Signs/Logo-Identity in the Major League Baseball Facility: Case Study of Tropicana Field". International Journal of Applied Sports Sciences. 23 (1): 251–270. doi:10.24985/ijass.2011.23.1.251.

- Chopra, Sonia (April 3, 2015). "Where to Eat at Tropicana Field, Home of the Tampa Bay Rays". Where to Eat at Tropicana Field, Home of the Tampa Bay Rays. Vox Media. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

External links

[edit] Media related to Tropicana Field at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tropicana Field at Wikimedia Commons- Ballpark Digest review of Tropicana Field

- Stadium site on MLB.com

- Tropicana Field Seating Chart

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by first ballpark

|

Home of the Tampa Bay Rays 1998–present |

Succeeded by current

|

| Preceded by first venue

|

Home of the Beef 'O' Brady's Bowl 2008–2017 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Tampa Bay Lightning 1993–1996 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Tampa Bay Storm 1991–1996 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Davis Cup Final Venue 1990 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament Finals Venue 1999 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the WWE ThunderDome 2020–2021 |

Succeeded by |

- Covered stadiums in the United States

- Ice hockey venues in Florida

- Defunct National Hockey League venues

- Sports venues completed in 1990

- Sports venues in St. Petersburg, Florida

- Defunct NCAA bowl game venues

- Music venues in Florida

- Tampa Bay Rays stadiums

- Baseball venues in Florida

- Tropicana Products

- PepsiCo buildings and structures

- Major League Baseball venues

- United Football League (2009–2012) venues

- 1990 establishments in Florida

- NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament Final Four venues

- 1990 Davis Cup

- Tampa Bay Lightning